Fr. Rosica, Fraud

Earlier this month, journalists discovered that Fr. Thomas Rosica—an influential and (it was believed) media-savvy Catholic priest—had plagiarized portions of some of his speeches and popular publications. After about a week of silence, he offered an apology, of sorts: “What I’ve done is wrong, and I am sorry about that.”

But the scale of the plagiarism suggested deeply ingrained habits—those of an insecure and systematically dishonest writer. And the “apology” seemed calculated to minimize the crime in three ways: Though he said he was sorry, he also insisted his plagiarism wasn’t malicious, he described it as unintentional (an unfortunate accident resulting from sloppy research habits), and he blamed it on others (some of his material is drafted by “interns”).

From a priest who should know better, this is worrying. In addition to boasting academic credentials (degrees and institutional affiliations), he has delivered and published lectures and addresses for prominent audiences, is CEO of a Canadian media company (Salt and Light Media), and has been a media attaché for various Vatican initiatives. This isn’t just any priest who has plagiarized: Rosica is a communications expert, a professional intellectual, an authority. More than most ministers of the Word, he traffics in words.

Given the extent of his theft, there was reason to expect that the plagiarizing had begun more than a decade ago, and might even be found in his scholarship. Sure enough, in the first essay I checked—published 25 years ago and related to one of his academic theses—Rosica had clearly and extensively plagiarized.

Others found more, pressure increased in the press and social media, and two days later—yesterday—he “apologized” again (only digging his hole deeper by claiming, incredibly, that his plagiarism was “never deliberate”). But his academic board memberships were already falling away; the story isn’t over, but one suspects that soon other organizations—perhaps including the Vatican Press Office, institutions that awarded him degrees, and even his media company—will be eager to cut ties.

Still, in the light—or rather, the darkness—of the Church’s larger clergy abuse scandal, a plagiarizing priest may hardly register. Rosica’s habit undermines his integrity, and the extent of his intellectual malpractice destroys his credibility in academic, professional, and ecclesiastical life. But given the faithful’s graver challenges, is a little cut-and-paste such a big deal for the Church?

Teachers often exhort: Don’t “steal” words and ideas, produce “original” work, and express it “in your own words.” This framing suggests why plagiarism is wrong, but it’s not adequate, even for students: What if the source of the borrowed text is offered for free, or contracted for sale? And how many assignments reward genuine originality as opposed to, say, accurate exegesis, clear analysis, or adequate understanding?

The real problem with plagiarism is not unoriginality but inauthenticity. Students need to do “their own work”—not by presenting novel ideas, but by presenting their own effort. The same applies to writing done outside the classroom. Anyone who claims to be an author is expressing words with a kind of authority and relying on a presumption of authenticity. When prosecuted as a crime, plagiarism is sometimes handled under intellectual property law. But plagiarism itself is not a traditional legal category, and someone can plagiarize even when there is no specific intellectual property claim.

The main victim of plagiarism isn’t the source’s original author, but the plagiarizing author’s audience. Plagiarism isn’t a violated property claim, but false representation: It is fraud. And like other forms of fraud, its gravity is both internal and external. It perverts the rational soul and damages the wider community.

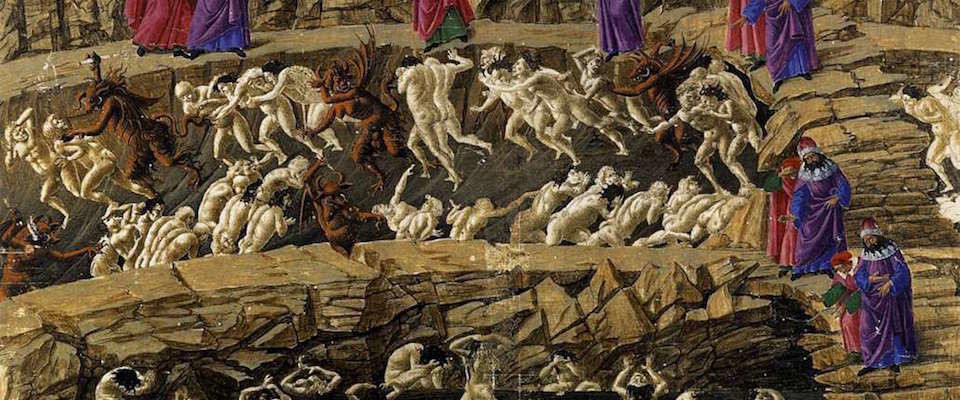

This is why Dante treated fraud with such detail in Inferno. Malebolge, the eighth circle of Hell, is a mockery of civic life—an inverted city populated by those who have undermined the very basis of community: trust. Higher up, one finds the perversions of the passions, but the ditches of Malebolge are populated by those who represent an astonishing diversity of social corruption caused by the abuse of truth—grifters and swindlers, cheaters and con-men, charlatans and mountebanks, manipulators and profiteers, simonists and barrators, schismatics and scandal-mongers, perjurers and manipulators, forgers and counterfeiters.

Thieves are here too, in the seventh ditch, as a reminder that theft expresses not just selfish greed, but a lie and a violation of community. But at the bottom, in the tenth ditch, Dante locates the falsifiers—of metals, persons, coins, and, finally, of words. There at the bottom of Malebolge is where the plagiarists belong, with the other language-falsifiers, at the threshold to betrayal and treason.

Dante’s infernal geography can help map the habitually plagiarizing “communications expert” onto the wider crisis of trust in the church. In “the abuse crisis,” the violation stems not only from sexual crimes—lapses of lust and perversions of appetite—but from deliberate, habitual, and systematically deceptive behavior. The church crisis is about pedophiles, harassers, and abusers, but it is also about panderers and seducers, false counselors and flatterers, hypocrites and impostors. Personal corruption is shrouded in systemic violations of social trust, individual physical transgressions covered in a culture of intellectual and spiritual perversion.

Does Fr. Rosica deserve mercy? Of course. But we should still be outraged at his long habit of linguistic fraud. Empty apologies are a lame attempt to hide from the natural (and, one hopes, healing) shame of corruption exposed.

Joshua P. Hochschild is Monsignor Robert R. Kline Professor of Philosophy at Mount St. Mary’s University.