Blogs | May. 10, 2017

Father Solanus Casey — Priest, Prophet, and Porter

The next time you run into failure or setback, turn to Father Solanus, the patron saint of apparent failure and setbacks. He knows all about it.

If you heard about a seminarian who struggled all the way through seminary, failed one language class after another, and then was ordained on the condition that he give neither doctrinal homilies nor hear confessions – you probably wouldn’t expect him to amount to much.

But Bernard Francis Casey – the sixth of 16 kids from Prescott, Wisconsin – was such a seminarian. And the world is about to find out how far he went in his chosen field.

Nicknamed Barney by his family but better known now as Father Solanus Casey, OFM Cap., this extraordinary figure recently advanced closer to sainthood with the Holy See’s May 4, 2017 announcement that Pope Francis has approved one of the innumerable miracles ascribed to Casey’s prayers.

But those who knew Father Solanus through his decades of service to the poor and the sick in Yonkers, New York, Harlem, and at St. Bonaventure’s in Detroit, either witnessed or heard of many hundreds of similar cures and prophetic happenings at the gentle hands of this holy man.

I first heard of him from his great nephew Kelly Casey, a fellow Franciscan University of Steubenville student and friend. The more I read about Kelly’s great uncle, the more I wanted to read about this simple priest with a heart for the poor and the hurting.

One incident from his life stands out. When Barney was working as a streetcar motorman in Superior, Wisconsin, he witnessed the stabbing of a woman in the street, accompanied by the blasphemous screaming of the man who had just savaged her with a knife. That moment branded itself in his brain: the maniacal yelling, the bright red flash of blood on the blade, the woman’s supine body on the pavement. To Barney, it was a singular manifestation of the reality of sin and the fallenness of the world – and an actual grace to seek after Him who would show men the meaning of true love and mercy. There was no turning back.

He was ordained in 1904, and began a life of priestly self-giving that would last until his last day on earth, July 31, 1957, the anniversary of his first Mass.

It’s the sheer ordinariness of his m.o. that gets you. No histrionics, no fanfare. He simply spoke quietly with the sick or troubled person, blessed him or her (often on the forehead) and said, “You’ll be fine. Everything is going to be okay.” Or, if the situation wasn’t to have a happy ending, Father Solanus would couch it in gentle, palatable terms. Either way, you came away changed, either strengthened for tough times, or dizzy with joy because of a healing.

The recipient of the miracle is a woman who suffered an incurable genetic skin condition (Father Solanus died of a similar virulent condition) and who went to his tomb to pray for some friends. Sensing an inner tug in her heart to beg healing for herself, she asked for the wiry Capuchin’s intercession and was instantly and visibly healed.

With the acceptance of the miracle, Venerable Solanus will become Blessed Solanus in a ceremony in Detroit later this year. He will be the second American-born male Blessed, after Servant of God Father Stanley Rother is beatified in Oklahoma City in September. Father Rother was martyred in 1981 in Guatamala – which jumped him to the head of the pack of candidates for sainthood.

Father Solanus underwent a slow winding white martyrdom, starting with the humiliation of being ordained a simplex priest, unable to deliver official sermons or hear confessions. Put in charge of the altar boy schedule and sacristan duties was a condition most men aspiring to the priesthood would find beyond intolerable.

But Solanus accepted his circumstances, seeing in humiliation the alchemy that produces humility – the virtue with which he is perhaps most identified. People soon understood that the quiet Capuchin who greeted them at the friary door had an unusual gift for really listening to their troubles, a gift that included striking healings that bring to mind St. Padre Pio or St. Andre Bessette, CSC, of Montreal. The astounding part is that it took the Congregation of the Causes of Saints so long to recognize one of Solanus’s miracles, there are so many to chose from.

I love the stories of future saints who knew each other. In the summer of 1935, then Brother Andre was in Detroit and had heard of Father Solanus. Brother was brought to the Saint Bonaventure Monastery and the two enjoyed a brief, somewhat humorous, meeting. None of the onlookers would have grasped the significance of the 65-year-old Capuchin vigorously shaking hands with the spry 90-year-old Holy Cross Brother. Both had become well known for their intercessory gifts. As Father Casey knew no French and Brother Andre spoke very little English, they did what they could do, and what came naturally: they blessed each other in Latin, the universal language of the Church.

Orthodox Catholics have a tendency to value intellect and the life of the mind. We admire scholars, wise professors and doctors, and profound authors. We tend to be slow to accept testimonies of healing. We take our faith clean and tidy. We’re quick to control events and people. But what happens when life throws a painful hardball? How do we face the terrible sword of suffering?

This is Solanus Casey’s sweet spot. He didn’t read German or Latin. He never wrote any books, probably couldn’t quote Thomas Aquinas, and he never traveled beyond where his superiors told him to go.

But he had what every Christian strives to be: he was another Jesus.

One of his recurrent teachings was, “Thank God ahead of time.” Father Solanus was convinced that anxiety and fear impeded God’s designs for His children, and he wondered why people didn’t pray with greater confidence. “We have to put God on the spot,” he’d say with an Irish twinkle in his eyes.

Because of his habit of divine spot-putting, the fame of Father Solanus’s sanctity spread far and wide beyond the grounds of the friaries he served in Michigan and New York. Line-ups trailed out onto the sidewalk and around the corner as people from all walks of life waited for their moment with the man who seemed to exude palpable joy. He told them of future happy events, of inevitable deaths, of surgical procedures that would be needed or not.

Yet no one thought him as “mysticalish” or strange. He was utterly normal, ordinary. According to one of his biographers, Father Michael Crosby, OFM Cap., Solanus’s most striking qualities were his eyes (soft blue) and his voice (slightly high-pitched, an echo of a childhood bout with diphtheria). His child-like aura is captured by the many extant photos of the soon-to-be-Blessed – playing his beat-up violin, ladling soup to the homeless in Harlem, grinning at something out of frame on a farm, listening intently to a couple in his porter’s office.

His body was exhumed in 1987 and was found to be remarkably intact, with some minor decomposition on his elbows. The remains were washed and given a new Capuchin habit and re-interred in his tomb at the Father Solanus Casey Center at the Saint Bonaventure Monastery in Detroit, where, to this day, thousands visit to stop and pray.

The next time you run into failure or setback, turn to Father Solanus, the patron saint of apparent failure and setbacks. He knows all about it.

But Bernard Francis Casey – the sixth of 16 kids from Prescott, Wisconsin – was such a seminarian. And the world is about to find out how far he went in his chosen field.

Nicknamed Barney by his family but better known now as Father Solanus Casey, OFM Cap., this extraordinary figure recently advanced closer to sainthood with the Holy See’s May 4, 2017 announcement that Pope Francis has approved one of the innumerable miracles ascribed to Casey’s prayers.

But those who knew Father Solanus through his decades of service to the poor and the sick in Yonkers, New York, Harlem, and at St. Bonaventure’s in Detroit, either witnessed or heard of many hundreds of similar cures and prophetic happenings at the gentle hands of this holy man.

I first heard of him from his great nephew Kelly Casey, a fellow Franciscan University of Steubenville student and friend. The more I read about Kelly’s great uncle, the more I wanted to read about this simple priest with a heart for the poor and the hurting.

One incident from his life stands out. When Barney was working as a streetcar motorman in Superior, Wisconsin, he witnessed the stabbing of a woman in the street, accompanied by the blasphemous screaming of the man who had just savaged her with a knife. That moment branded itself in his brain: the maniacal yelling, the bright red flash of blood on the blade, the woman’s supine body on the pavement. To Barney, it was a singular manifestation of the reality of sin and the fallenness of the world – and an actual grace to seek after Him who would show men the meaning of true love and mercy. There was no turning back.

He was ordained in 1904, and began a life of priestly self-giving that would last until his last day on earth, July 31, 1957, the anniversary of his first Mass.

It’s the sheer ordinariness of his m.o. that gets you. No histrionics, no fanfare. He simply spoke quietly with the sick or troubled person, blessed him or her (often on the forehead) and said, “You’ll be fine. Everything is going to be okay.” Or, if the situation wasn’t to have a happy ending, Father Solanus would couch it in gentle, palatable terms. Either way, you came away changed, either strengthened for tough times, or dizzy with joy because of a healing.

The recipient of the miracle is a woman who suffered an incurable genetic skin condition (Father Solanus died of a similar virulent condition) and who went to his tomb to pray for some friends. Sensing an inner tug in her heart to beg healing for herself, she asked for the wiry Capuchin’s intercession and was instantly and visibly healed.

With the acceptance of the miracle, Venerable Solanus will become Blessed Solanus in a ceremony in Detroit later this year. He will be the second American-born male Blessed, after Servant of God Father Stanley Rother is beatified in Oklahoma City in September. Father Rother was martyred in 1981 in Guatamala – which jumped him to the head of the pack of candidates for sainthood.

Father Solanus underwent a slow winding white martyrdom, starting with the humiliation of being ordained a simplex priest, unable to deliver official sermons or hear confessions. Put in charge of the altar boy schedule and sacristan duties was a condition most men aspiring to the priesthood would find beyond intolerable.

But Solanus accepted his circumstances, seeing in humiliation the alchemy that produces humility – the virtue with which he is perhaps most identified. People soon understood that the quiet Capuchin who greeted them at the friary door had an unusual gift for really listening to their troubles, a gift that included striking healings that bring to mind St. Padre Pio or St. Andre Bessette, CSC, of Montreal. The astounding part is that it took the Congregation of the Causes of Saints so long to recognize one of Solanus’s miracles, there are so many to chose from.

I love the stories of future saints who knew each other. In the summer of 1935, then Brother Andre was in Detroit and had heard of Father Solanus. Brother was brought to the Saint Bonaventure Monastery and the two enjoyed a brief, somewhat humorous, meeting. None of the onlookers would have grasped the significance of the 65-year-old Capuchin vigorously shaking hands with the spry 90-year-old Holy Cross Brother. Both had become well known for their intercessory gifts. As Father Casey knew no French and Brother Andre spoke very little English, they did what they could do, and what came naturally: they blessed each other in Latin, the universal language of the Church.

Orthodox Catholics have a tendency to value intellect and the life of the mind. We admire scholars, wise professors and doctors, and profound authors. We tend to be slow to accept testimonies of healing. We take our faith clean and tidy. We’re quick to control events and people. But what happens when life throws a painful hardball? How do we face the terrible sword of suffering?

This is Solanus Casey’s sweet spot. He didn’t read German or Latin. He never wrote any books, probably couldn’t quote Thomas Aquinas, and he never traveled beyond where his superiors told him to go.

But he had what every Christian strives to be: he was another Jesus.

One of his recurrent teachings was, “Thank God ahead of time.” Father Solanus was convinced that anxiety and fear impeded God’s designs for His children, and he wondered why people didn’t pray with greater confidence. “We have to put God on the spot,” he’d say with an Irish twinkle in his eyes.

Because of his habit of divine spot-putting, the fame of Father Solanus’s sanctity spread far and wide beyond the grounds of the friaries he served in Michigan and New York. Line-ups trailed out onto the sidewalk and around the corner as people from all walks of life waited for their moment with the man who seemed to exude palpable joy. He told them of future happy events, of inevitable deaths, of surgical procedures that would be needed or not.

Yet no one thought him as “mysticalish” or strange. He was utterly normal, ordinary. According to one of his biographers, Father Michael Crosby, OFM Cap., Solanus’s most striking qualities were his eyes (soft blue) and his voice (slightly high-pitched, an echo of a childhood bout with diphtheria). His child-like aura is captured by the many extant photos of the soon-to-be-Blessed – playing his beat-up violin, ladling soup to the homeless in Harlem, grinning at something out of frame on a farm, listening intently to a couple in his porter’s office.

His body was exhumed in 1987 and was found to be remarkably intact, with some minor decomposition on his elbows. The remains were washed and given a new Capuchin habit and re-interred in his tomb at the Father Solanus Casey Center at the Saint Bonaventure Monastery in Detroit, where, to this day, thousands visit to stop and pray.

The next time you run into failure or setback, turn to Father Solanus, the patron saint of apparent failure and setbacks. He knows all about it.

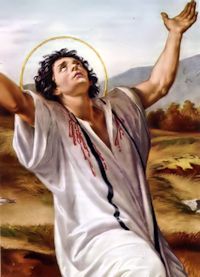

On the day after the solemnity of Christmas, we celebrate today the feast of St. Stephen, deacon and first martyr. At first glance, to join the memory of the "protomartyr" and the birth of the Redeemer might seem surprising because of the contrast between the peace and joy of Bethlehem and the tragedy of St. Stephen, stoned in Jerusalem during the first persecution against the nascent Church.

On the day after the solemnity of Christmas, we celebrate today the feast of St. Stephen, deacon and first martyr. At first glance, to join the memory of the "protomartyr" and the birth of the Redeemer might seem surprising because of the contrast between the peace and joy of Bethlehem and the tragedy of St. Stephen, stoned in Jerusalem during the first persecution against the nascent Church.