Giacometti and Gormley: The Art of Being

It’s rather fitting that his month, two sculpting greats, Alberto Giacometti and Antony Gormley, open solo shows in Hong Kong. Although born half a century apart, no two sculptors work has shared so much in common or drawn so much comparison.

There are a few names in sculpture that have endured above all and had the power to capture the public imagination generation after generation, and impact the development of the sculptural form: Michelangelo, Rodin, Henry Moore. Standing out amongst the dozens of art exhibitions cropping up this spring in Hong Kong are the solo shows of two other sculptors, one a modern master, and the other a contemporary supernova who has already firmly established himself both critically and publicly. Gagosian will be exhibiting ‘Giacometti Sans Fin’, a collection of materials and works by Swiss sculptor, painter and draughtsman, Alberto Giacometti, from the Giacometti Foundation. Meanwhile White Cube will exhibit the work of recently knighted British sculptor Antony Gormley, as well as unveiling a special large-scale public installation in Hong Kong to coincide with Art Basel HK in May.

It’s not just the celebrated nature of their work and careers that piques one’s interests. Neither needs much introduction; their works are iconic and celebrated internationally, both in the market and with the public. Giacometti is one of the highest selling sculptors, if not modern artists, on the auction market. His ‘L’Homme qui March I’ (1961), is one of the most expensive works bought at auction, selling at a 2010 Sotheby’s auction for USD$104.3 million. Three months later, ‘Grand Tête Mince’ (1955), a bronze bust, sold for USD$53.3 million. For a still living contemporary artist, Gormley’s work doesn’t fare too badly either; a smaller life-size model of ‘Angel of the North’ (1996) brought in USD5.57 million at a 2011 Christie’s auction, and demand for his work is so great that his galleries frequently have waiting lists. What is interesting, and rather apt, is that their shows coincide. Born half a century apart and influential in their respective artistic milieus, no two sculptors work has shared so much in common or drawn so much comparison.

‘Foule à un Carrefour’,

Collection Fondation Giacometti, Paris

© Estate Giacometti, 2014

Annette assize (petite), 1956, Collection Fondation Giacometti, Paris.

© Estate Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti and ADAGP, Paris) 2014

Surface similarities are glaringly obvious. Giacometti and Gormley both model their work on the human figure. While Gormley often uses his own image, a tall bean-pole of a body, to model his forms, Giacometti’s works are a reductive abstracted human form. But upon closer inspection, it becomes evident that Gormley and Giacometti’s repetitive forms are a dialogue with space and time, and a meditation on the human condition.

Giacometti came to prominence in the post-Second World War period, a one time surrealist influenced by primitive art hobnobbing with artists such as Joan Miro and Picasso. In the 1950s when abstract painting dominated in Europe and America, and modernity rejected the body, Giacometti’s singular dedication to the human form returned the human figure to art in the post-war period. He became an innovator of sculpture with his whittled down and ravaged, eroded, human forms, representative of the condition of modern man. His solitary figures, frozen in momentum, stretched out and flattened, are shrouded in solitude, anxiety, and doubt. Although the works themselves have bulkiness and mass carved away from them, the surrounding space is pregnant with the presence of the work, or filled with tension as the figures stand facing the unknown. Works like the iconic ‘L’Homme qui Marche I’, are frozen mid walk, inscribed with temporality. Time in space and the struggle of man is suggested through this eternal movement forward.

The works resonated with the post-war audience, but these abstracted silent lone figures speak of the existential drama of mankind still. It is his ability to “channel the energy of living subjects in his work”, says director of the Giacometti Fondation, Veronique Wiesinger, that makes Giacometti’s work so enduring and iconic. He is able to express “the fundamental quality of being human, once it is stripped of emotions and personal history and local culture; the interaction of all things and beings in the universe; the impermanence of everything, objects and living beings alike,” she continues.

In Gagosian’s exhibition, opening on 13 March, the gallery will be presenting texts, drawings, photographs, and archival documents from this period in Giacometti’s life and career that have never been seen until now, and of course several sculptures. The exhibition is based on Paris Sans Fin an artist’s book containing 150 unsigned original lithographs composed by Giacometti between 1957 and 1962, and published posthumously in 1969. The book contains lithographs of bistros the artist haunted, and friends such as philosopher Jean Paul Sartre. The author, Herbert Lust, a pioneering collector of Giacometti graphics and close friend of the artist, described the book as “the artist’s last testament to his own life and to modern art”. What we also get with Giacometti Sans Fin is an insight into Giacometti the artist, not just the artworks.

Where Giacometti’s work looks into an existential void, Gormley’s engages with the world in awe. For Gormley, a Turner prize-winner who almost became a monk, the body is a vehicle through which he can explore man’s spirituality and represents the opportunity for engagement and meditation. But the works are also a dialogue with the environment and space in which they are placed; it is the space in and around the works that fills them with purpose and meaning. In an era where man has lost touch with nature, Gormley draws our attention back to it. His works, like ‘Angel of the North’ encourages communion with the surrounding space. Stretching 54 metres across a hill in Gateshead, the winged human figure is Britain’s largest sculpture, a monolithic architectural totem overlooking the landscape. There is something pagan and primal about visiting this work, like taking a trip to Stonehenge.

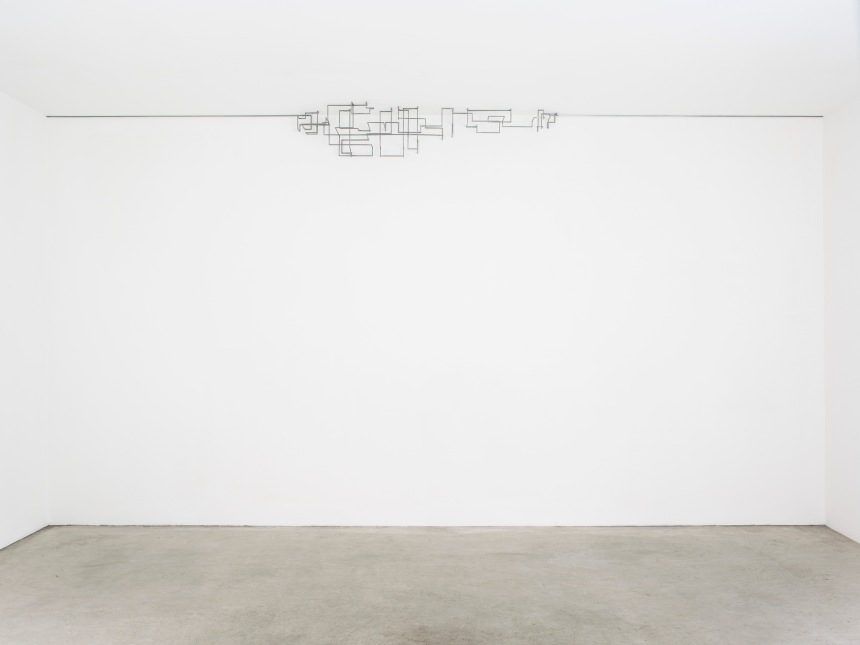

Gormley’s work is about engagement and the joy of looking and contemplating. By interacting with the work, the viewer becomes part of the piece. Such is the case with ‘Model’, a giant recumbent body composed of 100 tons of steel and measuring 105ft long and 18ft high, which visitors could walk through. Or ‘One & Other’ (2009), a project in which 2,400 people took it in turns to spend an hour on top of the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, becoming the work themselves. In States and Conditions, Hong Kong, Gormley’s upcoming Hong Kong show, the artist draws on the city’s dense urban condition in a play with the gallery’s architecture. The sculptures perfectly illustrate Gormley’s preoccupation with space and time, and like his previous works, encourage a dialogue with the viewer. ‘Murmur’ (2014) a large scale cuboid multiple ‘space frame’ fills the entire ground floor gallery allowing viewers just a small passage between the surrounding walls and the void contained inside the sculpture. It is a work that requires the body of the viewer to complete its story. Other works, like ‘Secure’ (2012) and ‘Transfer’ (2011) unconventionally occupy the space between wall and ceiling, or are suspended from the ceiling. The sculptures interfere with and animate the gallery’s architecture while at the same time challenging the viewer’s understanding of the space and the body in space. Gormley presents the human body as play, and “an endless source of happiness” says one London collector. “There is a combination of fragility and power, which I find amazing. For me he is the modern Giacometti. I don’t know any other contemporary sculptor that works so well on the human body.”

The antithesis of the heroic sculpture, both Giacometti and Gormley present figures that are faceless, anonymous, and devoid of statements of power or status quo. It is the body stripped of ego, stripped of detail, minimal yet wholly expressive at the same time. They are works about the state of being, a meeting of the artist’s subjectivity and the viewer’s experience. It is this simplicity that has made these two artists’ work so influential and sought after.

Giacometti Without End at Gagosian Gallery

13 March- 21 April, 2014

7/F Pedder Building, 12 Pedder St

Central, Hong Kong

http://www.gagosian.com

States and Conditions, Hong Kong at White Cube

28 March- 3 May, 2014

G/F, 50 Connaught Rd, Central, Hong Kong

http://www.whitecube.com

‘Transfer’, 2011,

© Antony Gormley

Photograph by Stephen White, London

‘Form’, 2013,

© Antony Gormley

Photograph by Stephen White, London

No comments:

Post a Comment