Dorothy Day, once a bohemian who believed in free love, is completely a saint for our time

What sets her apart from other holy men and women is that her early lifestyle was so at odds with her life after conversion

By Francis Phillips on Monday, 19 November 2012

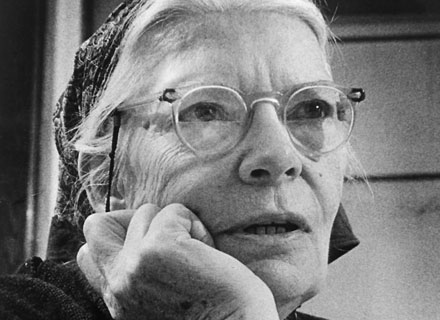

Dorothy Day's Cause has been endorsed by the US bishops' conference (Photo: CNS)

I was very glad to read in the Herald last Friday that the American bishops have now endorsed the Cause of Dorothy Day, the co-founder of the Catholic Worker Movement. Day, who died in 1980, was initially championed by the late Cardinal John O’Connor of New York; now his successor, Cardinal Timothy Dolan, is moving her hoped-for eventual canonisation forward.

Of course, anyone considered a candidate for canonisation is by definition holy and an example to the rest of us. What sets Dorothy Day apart from other 20th-century saints is that, like St Augustine, her early life was so at odds with her life after her conversion. We know that saints struggle and are tempted like other people; but we don’t always hear of their falls from grace along the way. Day is completely a saint for our time in that her life reflected all the idealism of a typical Left-wing journalist as well as the pitfalls of the feminist movement. For a time she was a Communist; she believed in free love; she lived a bohemian existence; she had an abortion which she later bitterly regretted. But as she writes in her autobiographical work, The Long Loneliness, she could never bring herself to reject religious faith as her contemporaries did in the political and journalistic circles in which she moved.

She recalled being stirred as a child by the sight of a neighbour, a poor Irish mother of a large family, praying on her knees in complete sincerity. It was when she was pregnant for the second time and was living in a beach house on Staten Island with her lover, Forster Batterham, that she received the grace to decide to have her baby, a daughter named Tamar, baptised. That decision, and her own conversion which followed it in 1926, cost her the relationship with Batterham, an agnostic; though she never stopped loving him she made the painful decision to separate from him and turn her back on her old life; eventually she moved into New York city.

It was a very lonely period. Like many who become saints – Josemaría Escrivá, Mother Teresa and Maximilian Kolbe also come to mind in the 20th century – she sensed she had a personal mission from God, but did not know what it was or how to go about it. Providence led her to meet an odd, charismatic Frenchman, Peter Maurin, who urged her to found a newspaper and start what became the Catholic Worker Movement. It began on the Feast of St Joseph the Worker in 1933. Day had found her mission. Her considerable writing gifts were fully employed running the Catholic Worker and all her heroic generosity came into play in founding Catholic Worker hostels for the poor and unemployed. She lived in one of these hostels herself, along with her young daughter Tamar, and relinquished all thought of any privacy from then on: meals, food, company, work were all shared within the shifting, noisy, demanding community of the hostel.

Day is famous for saying “Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed so easily.” She meant that people often use this term about others, in order to avoid their own obligation to holiness – and she was having none of it. Along with St Francis de Sales, I would love her to become in time the patron saint of journalists.

No comments:

Post a Comment