Christianity, like Shakespeare, never goes out of date

Unlike the pseudo-scripture of our age, the texts are timeless

By Fr Alexander Lucie-Smith on Friday, 2 November 2012

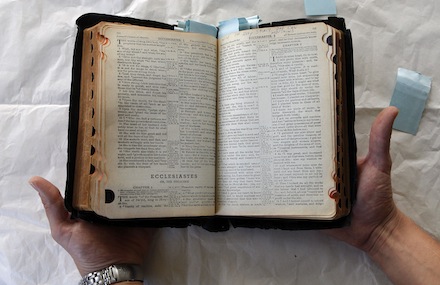

Timeless Dave Thompson/PA Wire/Press Association Images

The gospel for the Feast of All Saints was that of the Beatitudes, the start of the Sermon on the Mount, which is of course the most famous gospel passage of all. It is usually cited by moral theologians as being Jesus’ equivalent of the Ten Commandments, which were delivered through Moses on a different mountain. The Sermon is, like the Ten Commandments, something that does not grow old.

All this reminded me of what Ben Jonson said about Shakespeare: “He was not of an age, but for all time!” If that is true of Shakespeare – and it most certainly is -how much more is it true of the Gospels.

Again, I was reminded of something once said by Fr Francesco Pierli, the Comboni missionary, at a meeting I attended in Africa. “The Bible,” he said “is a moment in history that illuminates the whole of history.”

Shakespeare and the Bible are both products of their time, that reflect their time; but they are not locked into the culture that produced them. You do not need to travel back to Elizabethan England in order to understand the universal themes of, let us say, Romeo and Juliet. And you certainly do not have to enter into the world of the Ancient Near East to be able to read the Bible, which transcends history, time and place, while being, at the same time, securely anchored in all three. This is why, contrary to the expectations of so many, Christianity simply does not go out of date. So many pseudo-gospels – Marxism being the most obvious example – look very passé now; and quite a lot of modern trends will, fifty years from now, look anything but. But the Scriptures are as fresh now as when they were written.

Like all priests, I went to seminary, and like many I was disappointed by much of the teaching there. Some of it was good, but the part that really let me down, I felt, was the Scriptural part. The approach taken was something like this. To enter into the text, you need first to understand authorial intention; to understand authorial intention, you have to understand the author’s “living situation” (Sitz im leben); and to do that you have to reconstruct as fully as possible the concerns of that long dead person, which will involve understanding the language that person spoke. And so it was, before we could ever approach the Scriptures themselves, we had to spend hours and hours listening to very diffuse talk about the Hittites.

But the truth of the matter is, it seems to me, that people can engage with the text without any preamble whatever, and find it profitable. The text speaks directly. You do not have to know about the Hittites; you do not have to know about the Roman Empire to understand, for example, the accounts of Jesus’ encounter with Pontius Pilate. When Pontius Pilate asks “What is truth?” or says “Quod scripsi, scripsi” or “Ecce Homo”, these things speak for themselves.

Please do not think that I am going down the Lutheran path of Holy Scripture being its own interpretation. Rather I am saying that just as moral experience is at first hand, so too is the experience of God through the reading of the Bible. What that experience means, of course, has to be interpreted by the Church. But the foundational approach to Holy Scripture surely must be that of Saint Augustine: pick up and read. Tolle, lege!

Talking of great literature, consider this, from Book Eight of St Augustine’s Confessions, which is great theology too:

I was saying these things and weeping in the most bitter contrition of my heart, when suddenly I heard the voice of a boy or a girl, I know not which — coming from the neighbouring house, chanting over and over again, “Pick it up, read it; pick it up, read it.” Immediately I ceased weeping and began most earnestly to think whether it was usual for children in some kind of game to sing such a song, but I could not remember ever having heard the like. So, damming the torrent of my tears, I got to my feet, for I could not but think that this was a divine command to open the Bible and read the first passage I should light upon. For I had heard how Anthony, accidentally coming into church while the gospel was being read, received the admonition as if what was read had been addressed to him: “Go and sell what you have and give it to the poor, and you shall have treasure in heaven; and come and follow me.” By such an oracle he was forthwith converted to thee.

So I quickly returned to the bench where Alypius was sitting, for there I had put down the apostle’s book when I had left there. I snatched it up, opened it, and in silence read the paragraph on which my eyes first fell: “Not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying, but put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh to fulfil the lusts thereof.” I wanted to read no further, nor did I need to. For instantly, as the sentence ended, there was infused in my heart something like the light of full certainty and all the gloom of doubt vanished away.

No comments:

Post a Comment