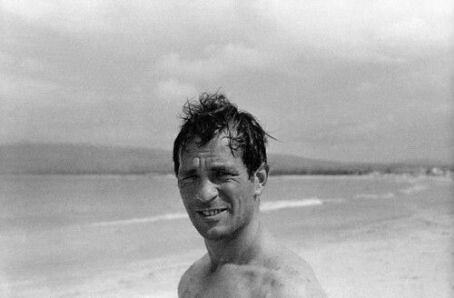

Jack Kerouac ... Only the lonely!

Jack Kerouac Reads from "On The Road"

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_MjPtem6ZbE

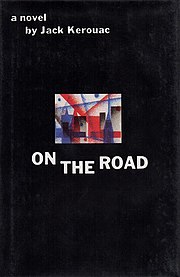

On the Road

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see On the Road (disambiguation).

| On the Road | |

|---|---|

1st edition | |

| Author(s) | Jack Kerouac |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Novel Beat |

| Publisher | Viking Press |

| Publication date | September 5, 1957 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 320 pages |

| ISBN | 978-0-141-18267-4 |

| OCLC Number | 43419454 |

| Preceded by | The Town and the City (1950) |

| Followed by | The Subterraneans (1958) |

When the book was originally released, The New York Times hailed it as "the most beautifully executed, the clearest and the most important utterance yet made by the generation Kerouac himself named years ago as "beat," and whose principal avatar he is."[1] In 1998, the Modern Library ranked On the Road 55th on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. The novel was chosen by Time magazine as one of the 100 best English-language novels from 1923 to 2005.[2]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Origins

Kerouac often promoted the story about how in April 1951 he wrote the novel in three weeks, typing continuously onto a 120-foot roll of teletype paper.[3] Although the story is true per se, the book was in fact the result of a long and arduous creative process. Kerouac carried small notebooks, in which much of the text was written as the eventful span of road trips unfurled. He started working on the first of several versions of the novel as early as 1948, based on experiences during his first long road trip in 1947. However, he remained dissatisfied with the novel.[4] Inspired by a thousand-word rambling letter from his friend Neal Cassady, Kerouac in 1950 outlined the "Essentials of Spontaneous Prose" and decided to tell the story of his years on the road with Cassady as if writing a letter to a friend in a form that reflected the improvisational fluidity of jazz.[5]The first draft of what was to become the published novel was written in three weeks in April 1951 while Kerouac lived with Joan Haverty, his second wife, at 454 West 20th Street in Manhattan, New York. The manuscript was typed on what he called "the scroll":[6] a continuous, one hundred and twenty-foot scroll of tracing paper sheets that he cut to size and taped together. The roll was typed single-spaced, without margins or paragraph breaks. In the following years, Kerouac continued to revise this manuscript, deleting some sections (including some sexual depictions deemed pornographic in the 1950s) and adding smaller literary passages.[7] Kerouac authored a number of inserts intended for On the Road between 1951 and 1952, before eventually omitting them from the manuscript and using them to form the basis of another work, Visions of Cody.[8] On the Road was championed within Viking Press by Malcolm Cowley and was published by Viking in 1957, based on revisions of the 1951 manuscript.[9] Besides differences in formatting, the published novel was shorter than the original scroll manuscript and used pseudonyms for all of the major characters.

Viking Press released a slightly edited version of the original manuscript on 16 August 2007 titled On the Road: The Original Scroll corresponding with the 50th anniversary of original publication. This version has been transcribed and edited by English academic and novelist Dr. Howard Cunnell. As well as containing material that was excised from the original draft due to its explicit nature, the scroll version also uses the real names of the protagonists, so Dean Moriarty becomes Neal Cassady and Carlo Marx becomes Allen Ginsberg etc.[10]

In 2007, Gabriel Anctil, a journalist of the Montreal's daily Le Devoir discovered, in Kerouac's personal archives in New York, almost 200 pages of his writings entirely in Quebec French, with colloquialisms. The collection included ten manuscript pages of an unfinished version of On the Road, written on January 19, 1951. The date of the writings makes Kerouac one of the earliest known authors to use colloquial Quebec French in literature.[11]

[edit] Plot summary

The two main characters of the book are the narrator, Salvatore “Sal” Paradise and his new friend Dean Moriarty, much admired for his care-free attitude and sense for adventure, a free-spirited maverick eager to explore all kicks, and an inspiration and catalyst for Sal’s travels. The novel contains five parts, three of them describing, each: a road trip from New York to the West Coast; one to Mexico; and the last part relating their final encounter when Dean comes to visit Sal in New York. During their trip and searches, they change and their relationship changes. The narrative takes place in the years 1947 to 1950, and is full of Americana and marks a specific era in jazz history, “somewhere between its Charlie Parker Ornithology period and another period that began with Miles Davis.” The novel is largely autobiographical, Sal being the alter ego of the author, and Dean standing for Neal Cassady.[edit] Part One

Sal has just been divorced and gotten over an illness. His life changes when he meets Dean Moriarty, who is "tremendously excited with life." As he says, “with the coming of Dean Moriarty began the part of my life you could call my life on the road”. Dean is “a side-burned hero of the snowy West” visiting New York with Marylou, his first wife. After having been thrown out by her he visits Sal who is living with his aunt in Paterson, New Jersey, wanting to learn “how to write”. In New York Dean meets an eclectic group of people, among them Carlo Marx, the poet. Sal describes their meeting as between “the holy con-man with the shining mind [Dean], and the sorrowful poetic con-man with the dark mind that is Carlo Marx." Carlo and Dean share stories about their friends and adventures around the country, and Sal gets the itch. After Dean’s departure, Sal is ready to go: ”Somewhere along the line I knew there would be girls, visions, everything; somewhere along the line the pearl would be handed to me.”Invited by Remi Boncoeur from San Francisco, Sal sets off in July 1947 with fifty dollars in his pocket. A false start leads him to Bear Mountain and Newburgh, and after his return to New York, he spends half his money taking the bus to Chicago. Mostly hitchhiking, he moves further west to Denver, meeting interesting characters along the way, such as Mississippi Gene and Montana Slim. In Denver, Sal hooks up with Carlo Marx, Dean, and their friends. There are parties — among them an excursion to the ghost town of Central City. Eventually Sal leaves by bus and gets to San Francisco, where he meets Remi Boncoeur and his girlfriend Lee Ann. Remi arranges for Sal to take a job as a night watchman at a boarding camp for merchant sailors waiting for their ship. Not holding this job for long, Sal hits the road again. “Oh, where is the girl I love?” he wonders. Soon, he meets the “cutest little Mexican girl” on the bus to Los Angeles. They stay together, travelling back to Bakersfield, then to Sabinal, “her hometown”, where her family works in the fields. He meets Terry's brother Ricky, who teaches him the true meaning of "mañana". Working in the cotton fields, Sal realizes that he is not made for this type of work. Leaving Terry behind, he takes the bus back to New York, and walks the final stretch from Times Square to Paterson, just missing Dean, who had come to see him, by two days.

[edit] Part Two

In December 1948 Sal is visiting relatives in Testament, Virginia, for Christmas. Dean shows up with Marylou, having left his second wife Camille and their newborn baby, Amy, in San Francisco. Dean also brings along Ed Dunkel. Sal’s Christmas plans are shattered as “now the bug was on me again, and the bug’s name was Dean Moriarty and I was off on another spurt around the country.” First they drive to New York, where they meet Carlo, and party. Dean wants Sal to make love to Marylou, but Sal declines. In Dean’s Hudson they take off from New York in January 1949, pass through Washington, DC, where Harry Truman’s inauguration takes place, and after an interlude with police, make it to New Orleans. In Algiers they stay with the morphine-addicted Old Bull Lee (“let’s just say now, he was a teacher”) and his wife Jane. Galatea joins her husband Ed Dunkel in New Orleans while Sal, Dean, and Marylou continue their trip. Lack of gas money forces them repeatedly to look for hitchhikers who would share travel expenses. Once in San Francisco, Dean rejoins with his wife Camille. “Dean will leave you out in the cold anytime it is in the interest of him” Marylou tells Sal. Both of them stay briefly in a hotel, but soon she moves out, following a nightclub owner. Sal is alone, and on Market Street has visions of past lives, birth and rebirth. Dean finds him and invites him to stay with his family. Together, they visit nightclubs and listen to Slim Gaillard and other jazz musicians. The stay ends on a sour note: "what I accomplished by coming to Frisco I don’t know,” and Sal departs taking the bus back to New York.[edit] Part Three

In the spring of 1949, Sal takes a bus from New York to Denver. He is depressed and “lonesome”; none of his friends are around. Envious of the life of black people, he feels that the “white world” does not offer “enough ecstasy… life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough night.” After receiving some money, he leaves Denver for San Francisco to see Dean. Dean’s wife is pregnant and unhappy, and Dean has injured his thumb by hitting Marylou, who was going with other men. “The thumb became the symbol of Dean’s final development. He no longer cared about anything (as before), but now he cared about everything in principle; that is to say it was all the same to him and he belonged to the world....” Camille throws them out, and Sal invites Dean to come to New York, planning to travel further to Italy. They meet Galatea who tells Dean off: ”You have absolutely no regard for anybody but yourself and your kicks.” Sal realizes she is right, Dean is the “HOLY GOOF”, but also defends him, as “he’s got the secret that we’re all busting to find out....” After a night of jazz and drinking in Little Harlem on Folsom Street, they depart. On the way to Sacramento they meet a "fag" who propositions them. Deans tries to hustle some money out of this but is turned down. During this part of the trip Sal and Dean have ecstatic discussions having found “IT” and “TIME”. Sal exclaims "the road is life." In Denver, however, a brief argument shows the growing rift between the two, when Dean reminds Sal of his age, Sal being the older of the two. Dean steals a car, but with his record — he had already been in jail for car theft — it is too dangerous to use it for travel. Instead, they get a '47 Cadillac from the travel-bureau that needs to be brought to Chicago. Dean drives most of the way, crazy, careless, often speeding over 100 miles per hour, bringing it in in a disheveled state. By bus they move on to Detroit and spend a night on Skid Row, Dean hoping to find his hobo father. From Detroit they share a ride to New York and arrive at the aunt’s new flat in Long Island. They go on partying in New York, where Dean meets Inez and gets her pregnant, while his wife is expecting their second child.[edit] Part Four

In the spring of 1950, Sal gets the itch to travel again, while Dean is working as a parking lot attendant in Manhattan, living with his girl friend Inez. Sal notices that he has been reduced to simple pleasures, listening to baseball games, and doing card tricks. By bus Sal takes the road again passing Washington, Ashland, Cincinnati, then St. Louis, and eventually reaching Denver. There he meets Stan Shephard, and the two plan to go to Mexico City, when they learn that Dean had bought a car and is on the way to join them. In a rickety '37 Ford sedan the three set off across Texas to Laredo, where they cross the border. They are ecstatic, having left “everything behind us and entering a new and unknown phase of things.” Their money buys more (10 cents for a beer), police are laid back, cannabis is readily available, and people are curious and friendly. The landscape is magnificent. In Gregoria, they meet Victor, a local kid, who leads them to a bordello where they have their last grand party, dancing to mambo, drinking, and having fun with under-age prostitutes. In Mexico City Sal becomes ill from dysentery and is “delirious and unconscious.” Dean leaves him, and Sal later reflects that “when I got better I realized what a rat he was, but then I had to understand the impossible complexity of his life, how he had to leave me there, sick, to get on with his wives and woes.”[edit] Part Five

Dean, having obtained divorce papers in Mexico, had first returned to New York to marry Inez, only to leave her and go back to Camille. After his recovery, Sal returns to New York in the fall. He finds a girl, Laura, and plans to move with her to San Francisco. Dean arrives to pick them up, but while Sal is taking a walk, he and Laura are left together. Sal realizes that it is all over. Dean heads back to Camille and Sal denies him a final ride. All that remains for Sal is the memory: he reflects on the images of the road, and closes “… I think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of Old Dean Moriarty the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarty."[edit] Reception and comments

The book initially received mixed reviews. In his review for The New York Times, Gilbert Millstein wrote, "its publication is a historic occasion in so far as the exposure of an authentic work of art is of any great moment in an age in which the attention is fragmented and the sensibilities are blunted by the superlatives of fashion," and praised it as "a major novel."[1] David Dempsey wrote that Kerouac delivered, "great, raw slices of America that give his book a descriptive excitement unmatched since the days of Thomas Wolfe."[12]Other reviewers were less impressed. Phoebe Lou Adams in Atlantic Monthly wrote that it "disappoints because it constantly promises a revelation or a conclusion of real importance and general applicability, and cannot deliver any such conclusion because Dean is more convincing as an eccentric than as a representative of any segment of humanity.[13]

Kerouac scholar Matt Theado points to the book's multi-layered reputation: "Kerouac's most famous novel comes with many associations that work to inform and mislead the reader before the cover is opened. The book is both a story and a cultural event."[14] David Ulin says in Book Forum that "even the most frantic of Kerouac’s writings were really the sagas of a solitary seeker: poor, sad Jack, adrift in a world without mercy when he’d rather be 'safe in Heaven dead.'"[15] "Kerouac was this deep, lonely, melancholy man," said Hilary Holladay at the University of Massachusetts.[15] "And if you read the book closely, you see that sense of loss and sorrow swelling on every page."[15] John Leland, author of Why Kerouac Matters: The Lessons of On the Road (They're Not What You Think), says "We're no longer shocked by the sex and drugs. The slang is passé and at times corny. Some of the racial sentimentality is appalling" but adds "the tale of passionate friendship and the search for revelation are timeless. These are as elusive and precious in our time as in Sal's, and will be when our grandchildren celebrate the book's hundredth anniversary."[16]

Kerouac later commented, On the Road "was really a story about two Catholic buddies roaming the country in search of God. And we found him. I found him in the sky, in Market Street San Francisco (those 2 visions), and Dean (Neal) had God sweating out of his forehead all the way. THERE IS NO OTHER WAY OUT FOR THE HOLY MAN: HE MUST SWEAT FOR GOD. And once he has found Him, the Godhood of God is forever Established and really must not be spoken about."[17]

[edit] Influence

On the Road has been a huge influence on many poets, writers, actors and musicians, including Bob Dylan, Van Morrison, Jim Morrison, Hunter S. Thompson and many more. "It changed my life like it changed everyone else's," Dylan would say many years later. Tom Waits, too, acknowledged its influence, hymning Jack and Neal in a song, and calling the Beats "father figures." At least two great American photographers were influenced by Kerouac: Robert Frank, who became his close friend — Kerouac wrote the introduction to Franks' book, The Americans — and Stephen Shore, who set out on an American road trip in the 1970s with Kerouac's book as a guide. It would be hard to imagine Hunter S. Thompson's road novel, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, had On the Road not laid down the template; likewise, films such as Easy Rider, Paris, Texas, even Thelma and Louise.[18]In his book "Light My Fire: My Life with The Doors", Ray Manzarek (keyboard player of The Doors) wrote "I suppose if Jack Kerouac had never written On the Road, The Doors would never have existed."

American pop singer Katy Perry has cited the book as the inspiration behind her song "Firework".[19][20]

[edit] The scroll exhibition

The original "scroll" still exists. It was bought in 2001 by Jim Irsay (Indianapolis Colts football team owner), for 2.43 million US dollars. It is available for public viewing, with the first 30 feet (9 m) unrolled. Between 2004 and 2005, the scroll was displayed in a number of museums and libraries in the US, Ireland and the UK.[edit] Film adaptation

Main article: On the Road (film)

A film adaptation of On the Road has been in the works for years. Russell Banks wrote a screenplay for producer Francis Ford Coppola, who bought the film rights for $95,000 in 1980.[21] The Brazilian director Walter Salles is now heading the project. After seeing Salles's The Motorcycle Diaries, Coppola decided on Salles and the production is underway.[22] In preparation for the film, Salles traveled the United States, tracing Kerouac's journey and filming a documentary on the search for On the Road.[23] Jose Rivera adapted the book into a screenplay. Coppola's American Zoetrope is producing the film, in association with MK2, Film4 in the U.K. and Videofilmes in Brazil. Sam Riley starred as Kerouac's alter ego Sal Paradise. Garrett Hedlund was cast as Dean Moriarty.[23] Kristen Stewart was cast as Mary Lou.[24] Kirsten Dunst will be playing Camille.[25] Filming started on August 2, 2010.[26] Filming took place in New Orleans, Montreal, Mexico and Argentina with a $25 million budget.[23][27][edit] Cultural references

In conjunction with the manuscript "scroll" tour[28] stop at Columbia College Chicago Center for Book & Paper Arts in 2008, A+D Gallery [29] of Columbia College presented an art exhibit called "Off the Beaten Road", curated by Julianna Cuevas and Megan Ross, "a 21st century take on the innovative ways of communication and dissemination in American life put forth by the Beats and encapsulated in Jack Kerouac’s seminal novel, 'On the Road'...through sound, installation, performance, video and fine art...Artists included Greg Stimac, Diana Guerrero-Macia, Dylan Strzynski, Third Coast International Audio Festival, and Jeff Gabel, among others.- Hip-Hop artist Sage Francis references the novel in his song 'Escape Artist'[30].

- The book can be seen on the dashboard of the car in the music video for P.O.D.'s 'Youth of the Nation'.

- Rapper Outasight refers in multiple songs to the novel.

[edit] Character key

"Because of the objections of my early publishers I was not allowed to use the same person's name in each work."[31]

| Real-life person[32] | Character name |

|---|---|

| Jack Kerouac | Sal Paradise |

| Gabrielle Kerouac | Sal's Aunt |

| Alan Ansen | Rollo Greb |

| William S. Burroughs | Old Bull Lee |

| Joan Vollmer | Jane |

| Lucien Carr | Damion |

| Neal Cassady | Dean Moriarty |

| Carolyn Cassady | Camille |

| Hal Chase | Chad King |

| Henri Cru | Remi Boncoeur |

| Bea Franco | Terry |

| Allen Ginsberg | Carlo Marx |

| Diana Hansen | Inez |

| Alan Harrington | Hal Hingham |

| Joan Haverty | Laura |

| Luanne Henderson | Marylou |

| Al Hinkle | Ed Dunkel |

| Helen Hinkle | Galatea Dunkel |

| Jim Holmes | Tom Snark |

| John Clellon Holmes | Tom Saybrook |

| Herbert Huncke | Elmer Hassel |

| Frank Jeffries | Stan Shephard |

| Gene Pippin | Gene Dexter |

| Ed Stringham | Tom Saybrook |

| Allan Temko | Roland Major |

| Bill Tomson | Roy Johnson |

| Helen Tomson | Dorothy Johnson |

| Ed Uhl | Ed Wall |

[edit] See also

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: On the Road |

- References in On the Road

- Off the Road (1990 book by Carolyn Cassady)

- Love Always, Carolyn

- Jack Kerouac Reads On the Road

- Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century

Jack Kerouac's On the Road is one of the most controversial American novels of the 20th century. When critics concede that the book and its author were instrumental in triggering the rucksack revolution, this is to damn with praise, as Kerouac is reduced to a one-book author (though he published some twenty volumes containing a wide range of prose and poetry). Moreover, the spiteful acknowledgement of a sociohistorical fact imports an aesthetic grudge against a novel that a close reading reveals to be far more conventional than most of its adversaries would would care to realize. Nor does the book propagate the shameless adoration of libidinous licentiousness for which it has been castigated in conservative quarters. Jack Kerouac's On the Road is one of the most controversial American novels of the 20th century. When critics concede that the book and its author were instrumental in triggering the rucksack revolution, this is to damn with praise, as Kerouac is reduced to a one-book author (though he published some twenty volumes containing a wide range of prose and poetry). Moreover, the spiteful acknowledgement of a sociohistorical fact imports an aesthetic grudge against a novel that a close reading reveals to be far more conventional than most of its adversaries would would care to realize. Nor does the book propagate the shameless adoration of libidinous licentiousness for which it has been castigated in conservative quarters. Kerouac, too, never understood what his book meant to the hordes of youngsters taking to the highways after the fashion of the characters peopling the narrative; but then, he was ill-fitted to grasp what his book had kindled in generations of young readers who felt stifled by the limitations of their parental homes. He never realized that he had prefigured their longings. |

Born, in 1922, in Lowell MA and baptized Jean-Louis Lebris de Kerouac, he learned English only as a second language. His parents, French Canadian immigrants, provided for a parochial, Catholic conservative, working-class background dominated by the mother who, in keeping with her heritage, felt more comfortable at speaking to her children in her French-Canadian dialect. The father, a printer, lost his job in the Great Depression and never recovered his standing. “Ti-Jean” (as Jack was pet-named by his mother) was a brooding, introverted child, a voracious, if indiscriminate reader. In high school, he was a minor sensation on the football field, the performanance at half-back, rather than academic excellence, earning him a scholarship to Columbia University after a preparatory year at Horace Mann, a private high school in New York City. College football, however, was more competitive than high-school games, and after breaking a leg in practice, he could not establish himself as a starter on the team. He also was in academic difficulties and had to make up for failing grades with extracurricular work during summer vacation. Kerouac left Columbia during his sophomore year, came back for a brief spell the following year, and after various odd jobs at gas stations and an honorable discharge from the Navy for an “indifferent character,” he joined the merchant marine in 1942. Born, in 1922, in Lowell MA and baptized Jean-Louis Lebris de Kerouac, he learned English only as a second language. His parents, French Canadian immigrants, provided for a parochial, Catholic conservative, working-class background dominated by the mother who, in keeping with her heritage, felt more comfortable at speaking to her children in her French-Canadian dialect. The father, a printer, lost his job in the Great Depression and never recovered his standing. “Ti-Jean” (as Jack was pet-named by his mother) was a brooding, introverted child, a voracious, if indiscriminate reader. In high school, he was a minor sensation on the football field, the performanance at half-back, rather than academic excellence, earning him a scholarship to Columbia University after a preparatory year at Horace Mann, a private high school in New York City. College football, however, was more competitive than high-school games, and after breaking a leg in practice, he could not establish himself as a starter on the team. He also was in academic difficulties and had to make up for failing grades with extracurricular work during summer vacation. Kerouac left Columbia during his sophomore year, came back for a brief spell the following year, and after various odd jobs at gas stations and an honorable discharge from the Navy for an “indifferent character,” he joined the merchant marine in 1942. Jack, who claimed he had completed his first novel at age eleven, had written for his high-school paper, contributed articles on local college sports to the Columbia Spectator, and, “. . . inspired by a new enthusiasm for the novels of Thomas Wolfe” (Ann Charters, Kerouac), began to keep extensive journals. Onboard the S.S. George Weems, “bound for Liverpool with 500-pound bombs in her hold, flying the red dynamite flag” (Charters), he wrote The Sea Is My Brother, which remained unpublished. After the war restless years followed, as Jack grew involved in the emerging underground scene of New York. (In part he was to record those experiences in On the Road.) During the winters he lived in his mother’s apartment in Ozone Park, L.I. (the father had died in the spring of 1946), from where he set out on frequent drinking bouts, often lasting for several days, to Times Square bars or to parties in Greenwich Village; the summers he spent roaming the country between New York, San Francisco, and Mexico City. Intermittently he worked on what was to become The Town And the City; accepted by Harcourt, Brace & Co. in 1949, the book appeared the following year and received lukewarm critical appraisal: “More often than not, the depth and breadth of his vision triumph decisively over his technical weaknesses,” the New York Times Book Review noted in November 1950. During the spring of 1951 Kerouac completed, in a three-week burst of writing, a typescript entitled variously “Beat Generation” and “On the Road,” different names for “. . . a scroll of paper three inches thick made up of one single-spaced, unbroken 120 feet long paragraph, . . .” as a friend recalls. In spite of several revisions and persistent efforts, Kerouac could not find a publisher for what he, according to Ann Charters, “. . . knew immediately . . . was the best writing he had ever done.” Editors were more interested in stories dealing with the scandalous lifestyle of these young, “Beat” bohemians than in their artistic work, until, in late 1955, Malcolm Cowley, senior adviser at Viking, accepted the book on the proviso that he and Kerouac go over the script together. When On the Road finally came out in 1957, the original typescript had been cut by one-third and amended to approximate the text to literary, orthographic, and printing conventions. “. . . Cowley riddled the original style of the manuscript there, without my power to complain, . . .,” Kerouac indicted later in an interview for The Paris Review. (The tangled genesis of the text prior to publication—some seven typescript versions are known to exist—may well prove futile all attempts at establishing a definitive edition.) In the wake of the clamor raised over the publication of Allen Ginsberg's “Howl” (the poem is dedicated to Kerouac, among others),On the Road made the bestseller lists and, except for a short lag in the early sixties, has continued to sell at a steady pace in America and Western Europe. The commercial success of On the Road prompted Viking to bring out more of Kerouac’s writings. By 1958 he had completed several manuscripts (Visions of Cody, Doctor Sax, and The Subterraneans, to name but a few), all autobiographical, loose in form, and written in the new prose style which he had developed in the meanwhile and called “Spontaneous Prose”: long, unpremeditated sentences full of associations, put to paper in the way they came to his mind; highly personal, often idiosyncratic accounts which were at times inherently contradictory; as he phrased it himself, in the vaguely programmatic “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose”:

The editors insisted on something conventional and chose The Dharma Bums because it was close to On the Road in scope, contents, and method of presentation. The book was inspired by Kerouac’s friendship with the Californian poet Gary Snyder, who became the model for Japhy Ryder, the hero of The Dharma Bums. Snyder had introduced Kerouac to Buddhist texts, the influence of which is traceable in On the Road and, more conspicuously, in The Dharma Bums. But Kerouac 'a infatuation with Eastern mysticism and religions was only transitory. At heart he always remained a devout Catholic, in his own personal way. He writes in “The Origins of the Beat Generation,” an article for Playboy:

|

Kerouac had always been an introverted, brooding, melancholic loner who preferred watching from the side over actively participating in his friends' hullabaloos; during the Sixties, his health deteriorating from continuous abuse of alcohol and benzedrine, he became utterly estranged from the world and retreated to his mother's home. He felt his work was misunderstood by the reading public, for whom he had become, due to his semi-fictitious heroes Dean Moriarty and Japhy Ryder, a cult figure and a pioneer of the newly emerging liberal movement. His political attitude was diametrically opposed to that of the majority of his readers as well as to that of his former close friend Allen Ginsberg. Kerouac spoke out in favor of the American engagement in Vietnam; in the interview for The Paris Review he explained: Kerouac had always been an introverted, brooding, melancholic loner who preferred watching from the side over actively participating in his friends' hullabaloos; during the Sixties, his health deteriorating from continuous abuse of alcohol and benzedrine, he became utterly estranged from the world and retreated to his mother's home. He felt his work was misunderstood by the reading public, for whom he had become, due to his semi-fictitious heroes Dean Moriarty and Japhy Ryder, a cult figure and a pioneer of the newly emerging liberal movement. His political attitude was diametrically opposed to that of the majority of his readers as well as to that of his former close friend Allen Ginsberg. Kerouac spoke out in favor of the American engagement in Vietnam; in the interview for The Paris Review he explained:

Shadows of fatalism and a profound pessimism permeate his later writing, for instance, The Vanity of Duluoz. Resignation, that all is “vanity,” rings through the last attempt at reshaping the legend he had begun with The Town And the City. Conspicuously, the two books cover roughly the same period of time, from the last years in Lowell to the father's death in New York City; while not exactly cheerful, the tone of The Town And the City, characterized by a longing to restore the happy days of childhood, had to give way to a deep sense of irrevocable loss. He wrote in the preface of Visions of Cody: “My work comprises one vast book like Proust's Remembrance of Things Past, except my remembrances are written on the run instead of afterwards in a sickbed.” The comparison, half-correct at best, sheds a distinct light on the author’s ambitions and misperceptions. Jack Kerouac died on October 21, 1969, “of hemorrhaging esophageal varices, the classic drunkard’s death,” according to Gerald Nicosia, the author of Memory Babe, a near-definitive critical biography. |

Jack Kerouac read by Johnny Depp

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hBKGfPg4A6c&feature=related

No comments:

Post a Comment