Who Was Titus Brandsma?

Father Brandsma’s beatification cause opened in the Dutch Diocese of Den Bosch in 1952. It was the first process for a candidate killed by the Nazis.

The first canonization ceremony for more than two and a half years will take place on May 15. Among the 10 candidates who will be proclaimed saints by Pope Francis that day is Titus Brandsma.

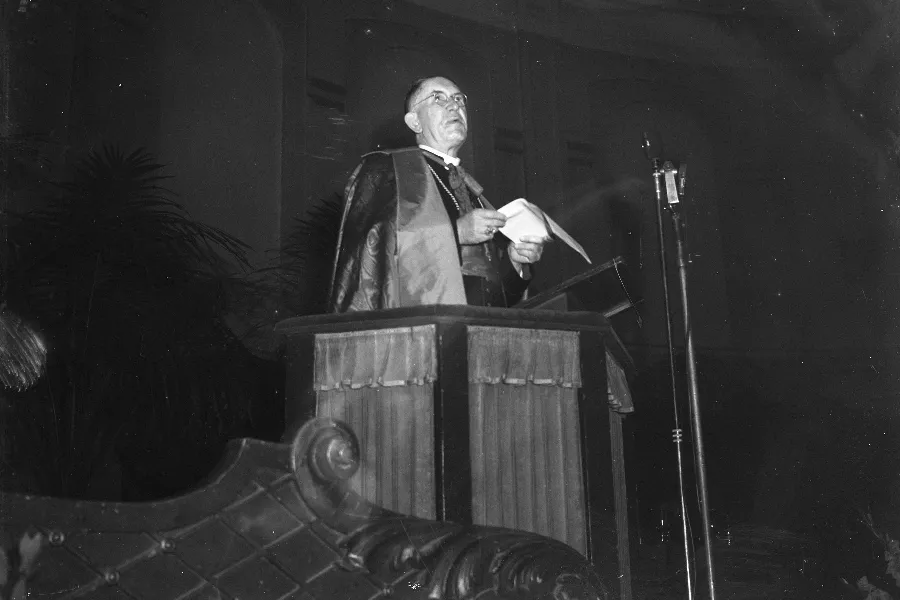

Many Catholics are familiar with Brandsma’s portrait: his pale, steady eyes, prominent ears, and buoyant hair. But who was the man behind the steel-rimmed glasses?

The 2 Vocations of Titus Brandsma

Titus Brandsma was born in the Netherlands, a country bordering Belgium and Germany, on Feb. 23, 1881. His parents named him Anno Sjoerd Brandsma and he grew up in the rural setting of Oegeklooster in the province of Friesland. His family lived on the proceeds of the milk and cheese produced by their dairy cattle.

Brandsma felt a calling to the religious life and joined the Carmelite monastery in Boxmeer, southeastern Netherlands, in 1898, taking his father’s name, Titus, as his religious name.

Although the Carmelites are known for separating themselves from worldly affairs and engaging in contemplative prayer, Brandsma felt called to a second vocation that would draw him into the drama of interwar Europe: that of journalism.

In the years ahead, he would successfully combine the two seemingly contrasting vocations.

A Globetrotter with a Strong Head for Whiskey

Brandsma was ordained to the priesthood on June 17, 1905. After studying in Rome, he returned to home to work in the field of Catholic education.

When the Catholic University of Nijmegen was founded in 1923, he joined the faculty, rising to become the institution’s rector magnificus, or head, in 1932.

With fears of a second world war rising in Europe, Father Brandsma embarked on a lecture tour of Carmelite foundations in the United States in 1935.

To improve his English, he visited Ireland, staying with Carmelite communities in Dublin and the picturesque coastal town of Kinsale.

During the trip, he met with Éamon de Valera, the then head of government of the Irish Free State. The Irish Carmelites were reportedly impressed by Father Brandsma’s ability to consume whiskey without ill effects.

Shortly before he crossed the Atlantic, Father Brandsma was appointed spiritual adviser to the staff of more than 30 Catholic newspapers in the Netherlands by the future Cardinal Johannes de Jong of Utrecht.

Upon arrival in the U.S., he traveled in the East and Midwest, giving lectures at the request of his superiors in Rome.

He was struck with wonder at Niagara Falls, writing in his journal: “I see God in the work of his hands and the marks of his love in every visible thing. I am seized by a supreme joy which is above all other joys.”

A Dangerous Mission

Throughout the 1930s, Father Brandsma watched aghast as Adolf Hitler strengthened his grip on neighboring Germany. The friar sharply criticized Nazi policies in newspaper articles and lectures. “The Nazi movement is a black lie,” he said. “It is pagan.”

After Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands on May 10, 1940, the authorities imposed severe restrictions on the Church. They ordered Catholic schools to expel Jewish students, barred priests and religious from serving as high school principals, restricted charitable collections, and censored the Catholic press. The Dutch bishops asked Father Brandsma to plead their cause, but without success.

In 1941, the bishops spoke out boldly against the Nazis. Their interventions infuriated Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the Reich commissioner of the German-occupied Netherlands, who sought ways of striking back.

When Dutch newspapers were told to accept advertisements and press releases from their Nazi overlords, the archbishop of Utrecht asked Father Brandsma to tell the country’s Catholic editors that they should refuse the order.

According to an account in the 1983 book No Strangers to Violence, No Strangers to Love, by Father Boniface Hanley, Archbishop de Jong underlined that the mission was dangerous and the Carmelite was not obliged to accept it.

“Father Titus knew exactly what I said, and he freely and willingly accepted the duty,” Archbishop de Jong later recalled.

Father Brandsma traveled around the Netherlands delivering letters to the editors that explained the rationale for the bishops’ decision. He was trailed by the Gestapo, Nazi Germany’s political police.

‘If It Is Necessary, We Will Give Our Lives’

Father Brandsma managed to visit 14 editors before he was arrested on Jan. 19, 1942, at the monastery in Boxmeer. As the Gestapo prepared to take him away, he knelt before his superior and received his blessing.

“Imagine my going to jail at the age of 60,” Father Brandsma said to the man arresting him.

The friar was taken to a prison in the seaside town of Scheveningen, where the interrogating officer demanded to know why he had disobeyed state regulations.

“As a Catholic, I could have done nothing differently,” Father Brandsma responded, according to Father Hanley.

The officer, Captain Paul Hardegen, later asked Father Brandsma to express in writing why his countrymen scorned the Dutch Nazi party.

“The Dutch,” the friar wrote, “have made great sacrifices out of love for God and

No comments:

Post a Comment