Ti Jean

I just love this ... Jack Kerouac's description of a Christmas homecoming from THE DHARMA BUMS:

Behind the house was a great pine forest where I would spend all that winter and spring meditating under the trees and finding out by myself the truth of all things. I was very happy. I walked around the house and looked at the Christmas tree in the window. A hundred yards down the road the two country stores made a bright warm scene in the otherwise bleak wooded void. I went to the dog house and found old Bob trembling and snorting in the cold. He whimpered glad to see me. I unleashed him and he yipped and leaped around and came into the house with me where I embraced my mother in the warm kitchen and my sister and brother-in-law came out of the parlor and greeted me, and little nephew Lou too, and I was home again.

They all wanted me to sleep on the couch in the parlor by the comfortable oil-burning stove but I insisted on making my room (as before) on the back porch with its six windows looking out on the winter barren cottonfield and the pine woods beyond, leaving all the windows open and stretching my good old sleeping bag on the couch there to sleep the pure sleep of winter nights with my head buried inside the smooth nylon duck-down warmth. After they'd gone to bed I put on my jacket and my earmuff cap and railroad gloves and over all that my nylon poncho and strode out in the cotton-field moonlight like a shroudy monk. The ground was covered with moonlit frost/The old cemetery down the road gleamed in the frost. The roofs of nearby farmhouses were like white panels of snow.

…

The following night was Christmas Eve which I spent with a bottle of wine before the TV enjoying the shows and the midnight mass from Saint Patrick's Cathedral in New York with bishops ministering, and doctrines glistering, and congregations, the priests in their lacy snow vestments before great official altars not half as great as my straw mat beneath a little pine tree I figured. Then at midnight the breathless little parents…

I also love this from Charles Dickens' A CHRISTMAS CAROL:

"There’s another fellow," muttered Scrooge; who overheard him: "my clerk, with fifteen shillings a week, and a wife and family, talking about a merry Christmas. I’ll retire to Bedlam."

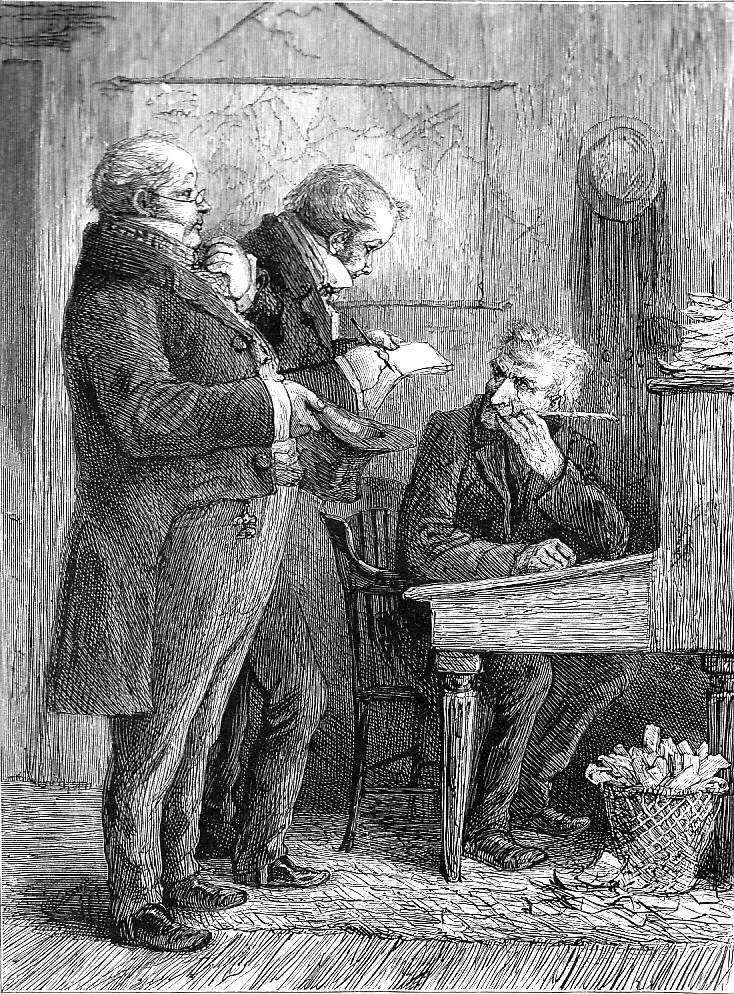

This lunatic, in letting Scrooge’s nephew out, had let two other people in. They were portly gentlemen, pleasant to behold, and now stood, with their hats off, in Scrooge’s office. They had books and papers in their hands, and bowed to him.

"Scrooge and Marley’s, I believe," said one of the gentlemen, referring to his list. "Have I the pleasure of addressing Mr. Scrooge, or Mr. Marley?"

"Mr. Marley has been dead these seven years," Scrooge replied. "He died seven years ago, this very night."

"We have no doubt his liberality is well represented by his surviving partner," said the gentleman, presenting his credentials.

It certainly was; for they had been two kindred spirits. At the ominous word "liberality," Scrooge frowned, and shook his head, and handed the credentials back.

CHRISTMAS CAROL SINGING IN CIDER WITH ROSIE ... Laurie Lee

The week before Christmas, when the snow seemed to lie thickest, was the moment for carol-singing; and when I think back to those nights it is to the crunch of snow and to the lights of the lanterns on it. Carol-singing in my village was a special tithe for the boys, the girls had little to do with it. Like hay-making, blackberrying, stone-clearing and wishing-people-a- happy-Easter, it was one of our seasonal perks.

By instinct we knew just when to begin it; a day too soon and we should have been unwelcome, a day too late and we should have received lean looks from people whose bounty was already exhausted. When the true moment came, exactly balanced, we recognised it and were ready.

So as soon as the wood had been stacked in the oven to dry for the morning fire, we put on our scarves and went out through the streets calling loudly between our hands, till the various boys who knew the signal ran out from their houses to join us.

One by one they came stumbling over the snow, swinging their lanterns around their heads, shouting and coughing horribly.

'Coming carol-barking then?'

We were the Church Choir, so no answer was necessary. For a year we had praised the Lord, out of key, and as a reward for this service - on top of the Outing - we now had the right to visit all the big houses, to sing our carols and collect our tribute.

Eight of us set out that night. There was Sixpence the Tanner, who had never sung in his life (he just worked his mouth in church); The brothers Horace and Boney, who were always fighting everybody and always getting the worst of it; Clergy Green, the preaching maniac; Walt the bully, and my two brothers. As we went down the lane, other boys, from other villages, were already about the hills, bawling 'Kingwensluch', and shouting through keyholes 'Knock on the knocker! Ring at the Bell! Give us a penny for singing so well!' They weren't an approved charity as we were, the Choir; but competition was in the air.

Our first call as usual was the house of the Squire, and we trouped nervously down his drive.

A maid bore the tidings of our arrival away into the echoing distances of the house. The door was left ajar and we were bidden to begin. We brought no music, the carols were in our heads. 'Let's give 'em 'Wild Shepherds', said Jack. We began in confusion, plunging into a wreckage of keys, of different words and tempos; but we gathered our strength; he who sand loudest took the rest of us with him, and the carol took shape if not sweetness.

Suddenly, on the stairs, we saw the old Squire himself standing and listening with his head on one side.

He didn't move until we'd finished; then slowly he tottered towards us, dropped two coins in our box with a trembling hand, scratched his name in the book we carried, give us each a long look with his moist blind eyes, then turned away in silence.

As though released from a spell, we took a few sedate steps, then broke into a run for the gate. We didn't stop till we were out of the grounds. Impatient, at least, to discover the extent of his bounty, we squatted by the cowsheds, held our lanterns over the book, and saw that he'd written 'Two Shillings'. This was quite a good start. No one of any worth in the district would dare to give us less than the Squire.

Mile after mile we went, fighting against the wind, falling into snowdrifts, and navigating by the lights of the houses. And yet we never saw our audience. We called at house after house; we sang in courtyards and porches, outside windows, or in the damp gloom of hallways; we heard voices from hidden rooms; we smelt rich clothes and strange hot food; we saw maids bearing in dishes or carrying away coffee cups; we received nuts, cakes, figs, preserved ginger, dates, cough-drops and money; but we never once saw our patrons.

Eventually we approached our last house high up on the hill, the place of Joseph the farmer. For him we had chosen a special carol, which was about the other Joseph, so that we always felt that singing it added a spicy cheek to the night.

We grouped ourselves round the farmhouse porch. The sky cleared and broad streams of stars ran down over the valley and away to Wales. On Slad's white slopes, seen through the black sticks of its woods, some red lamps burned in the windows.

Everything was quiet: everywhere there was the faint crackling silence of the winter night. We started singing, and we were all moved by the words and the sudden trueness of our voices. Pure, very clear, and breathless we sang:

'As Joseph was walking He heard an angel sing;

'This night shall be the birth-time

Of Christ the Heavenly King.

He neither shall be bored

In Housen nor in hall

Not in a place of paradise

But in an ox's stall .....

And two thousand Christmases became real to us then; The houses, the halls, the places of paradise had all been visited; The stars were bright to guide the Kings through the snow; and across the farmyard we could hear the beasts in their stalls. We were given roast apples and hot mince pies, in our nostrils were spices like myrrh, and in our wooden box, as we headed back for the village, there were golden gifts for all.

No comments:

Post a Comment