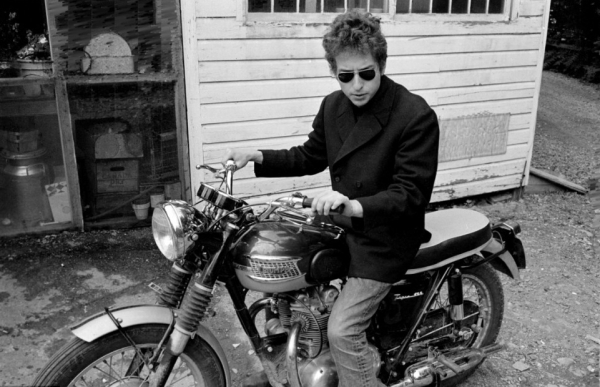

What If … Bob Dylan’s Motorcycle Hadn’t Crashed …

For most Bob Dylan historians, his infamous motorcycle wreck on July 29, 1966 marked a real turning point in his career and it changed the way he lived his life for much of the ensuing decade.

Dylan cut his hair, took up painting as a serious avocation, started referring to the Bible in earnest in his songs and morphed into the most dedicated family man around.

His music went through a stunning transformation as well after the crash, moving from a heavy rock and roll tone to a swinging-country sound. Before the accident, he had been making incendiary rock and roll music on stage with The Hawks. Although it was remarkable stuff, Dylan got booed for his trouble all over the world.

Today, it seems nothing but insane that “fans” so strongly showed their disapproval of their hero as he was presenting the greatest live music that anybody had ever heard — and all because he had the audacity to turn his back on the folk-music scene and follow his muse to rock and roll. Insane!

Dylan concluded a punishing world tour at the end of May 1966 and retreated to Woodstock, with his wife Sara and their two children (one of whom, a five-year-old daughter, had originated from Sara’s first marriage). He needed to recharge his batteries but instead faced a very busy summer ahead. He had tasks ranging from rehearsing with his band for another extended U.S. tour that fall — while girding for the inevitable loud booing at home — writing new songs, polishing off a book for MacMillan and editing an hourlong TV show for ABC about the just-finished series of concerts in England.

But Dylan was fried. He just wanted to live a normal, non-celebrity life in upstate New York as a 25-year-old family guy. Lots of luck.

On that fateful day of July 29, he had a motorcycle spill in Woodstock. The severity of his injuries has been widely debated ever since. But he was hurt badly enough to be able to shelve all of his upcoming obligations.

For nearly a year, he didn’t record any songs. He wouldn’t step on a stage until January 1968. As a writer pointed out about Dylan in that period, he was more proficient at cranking out babies than new albums. He remained as popular with his fans as ever. They continued to buy his old records and waited anxiously for any news of his recovery. Dylan, perhaps unwittingly, found that the more reclusive he acted, the more curious the public became. As he observed to Cameron Crowe in a 1985 interview for the “Biograph” liner notes, “there is power in darkness.”

When Dylan emerged from the shadows, he had a different sound in mind, something rootsy, which the music critics said smacked of Americana (whatever that may be). He and his friends in The Hawks were content to work in the country, at their pace, not the record company’s. They made music to please themselves. This creative approach was revolutionary (and soon-to-be oft-copied: see Traffic).

But…

What if Dylan hadn’t crashed?

We would have had his book Tarantula, his TV show Eat the Document and, probably, a batch of new recordings to puzzle over, not to mention the Dylan sound unleashed on the American heartland in a scheduled 65-concert swing that fall, kicking off with a big how at the Yale Bowl.

We just might have gotten, too, a fantastic rock and roll record as a follow-up to “Blonde on Blonde.” The musicians had gotten both tight and expressive on stage during their world your. It’s likely that they shared a sense of simpatico that would make it a relatively un-stressful task for them to make a new album in the studio.

Or, maybe Columbia, would have released the first Dylan live album in time for the Christmas rush.

Dylan might have stayed in the rock and roll phase of his career a while longer. Who knows. If he hadn’t suffered the accident, he might never have thought to create an album that sounded anything like like “John Wesley Harding.”

Or he might have continued too live on the edge of sanity and become a casualty of the celebrity fast lane — “another accident statistic,” as he would sing on “Slow Train Coming” in 1979.

He admitted in a subsequent interview, “I deserved to crash.” But he didn’t crumble and fade away. He had the strength and support system, in his wife Sara, to see the wisdom of slowing down (listen to “Shelter from the Storm”).

We’ll never really know whether Dylan manipulated people by claiming to have a serious motorcycle crash in 1966. It seems cynical and calculating to make this suggestion at all. But we still have to wonder.

It’s fascinating to ponder what kind of new music Dylan might have recorded in the autumn of 1966 or the winter of 1967. Just as “Blonde on Blonde” had been a departure from the bluesy sound of “Highway 61 Revisited,” we can suppose that Dylan would have again carved out a new musical territory for himself. Who would he have chosen to record with? The Hawks? And where? New York City or Nashville once again? Would he have been capable of continuing the electric winning streak that had begun in early 1965 — a lifetime ago, by mid-1966 — with “Bringing It All Back Home?”

Would there have been the by-then requisite long, album closer, too?

Mostly, I wonder where his head was at, musically, at that time. He would have heard and consumed “Revolver” and “Pet Sounds” and the other groundbreaking albums coming on to the scene. How might those records have influenced Dylan, if at all?

Bob Dylan probably would have declined to spend hours and hours in the recording studio, as his peers had been doing to brilliant results. He’d prefer to be out playing somewhere.

What if … his motorcycle hadn’t crashed? I still wonder about that.

No comments:

Post a Comment