Neuroscience and Bob Dylan?

Give me a break!

Imagine: How Creativity Works by Jonah Lehrer – review

A self-regarding how-to guide through the creative process

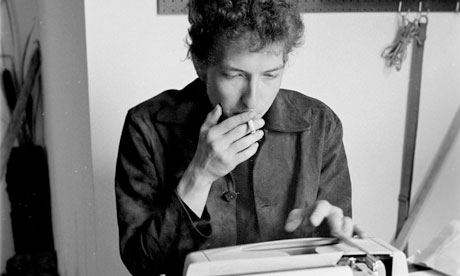

Where did that come from? Bob Dylan in 1964. Photograph: Douglas R. Gilbert/Redferns

How did Bob Dylan write "Like a Rolling Stone"? The pop-science writer Jonah Lehrer wasn't there, but he pretends to know anyway. Inspired by Dylan's own description of "vomiting" forth the song's lyrics, Lehrer peers inside the singer's 1965 skull and announces confidently that the "right hemisphere" of Dylan's brain was combining "scraps" or "fragments" of existing songs and poetry in a "mental blender", before spitting out a set of "lyrics that make little literal sense".

Strange, because "How does it feel / To be without a home" and so forth makes a fair amount of literal sense to me. The amazing presumption of Lehrer's description, the shattering banality of its explanation, and its mystifying stupidity are all entirely characteristic of a phenomenon best branded "neuroscientism". (The term has been employed by the philosopher Colin McGinn and the critical neuroscientist Raymond Tallis, among others.) Scientism is the confidence that science can explain all aspects of human life; neuroscientism is the more specific promise that brain-scans (using the limited current technologies of fMRI and EEG) can explain the workings of the mind.

Lehrer's neuroscientistic method consists of paraphrasing brain-imaging studies, grossly inflating what can be properly inferred from them, and so purporting to explain "creativity" or "imagination". He doesn't bother to distinguish between the two – presumably Coleridge, for example, can have had nothing interesting to say on the matter. As any good neuroscientistic believer should, he regularly insults the preceding centuries of thought on his topic, dismissing it all as "completely wrong". Lehrer has a rage, indeed, to insist on the novelty of his extrapolations from the research, which usually means misrepresenting conventional wisdom. "It's commonly assumed that the best way to solve a difficult problem is to relentlessly focus," he writes, but people have always known that going for a walk or sleeping on it – or, like Archimedes, taking a bath – can help. Nor did we need to wait for colourful neuro-pictures to learn that people sometimes have good ideas during daydreams, or on holiday.

The inconvenient truth is that observing which areas of the brain light up on a screen during experiments tells us little about "how creativity works". The "right hemisphere" is here suggested to be more verbally free-associative (handling "connotation"), as opposed to the pedantically literal left hemisphere (handling "denotation").

Lehrer doesn't realise, bizarrely, that Dylan could not have written "Like a Rolling Stone" without attending to the literal meanings of words – which means, on this crude scheme, that his left hemisphere, as well as his right, must have been hard at work. So the anatomical locus of creativity is not narrowed down after all. Throughout, the author intones the jargon names for many different brain structures that, he says, are all important for creativity (even as he occasionally mumbles a confession that their "precise function" is unknown): not just the right hemisphere but also the "anterior superior temporal gyrus", the "medial prefrontal cortex", the "dorsolateral prefrontal cortex", the "neural highway" of the dopamine system, and even "the primitive midbrain". But this expansive catalogue of crucial parts merely invites us to conclude, by the end, that pretty much all of the brain has to be involved in any complex creative work. Which effectively leaves us back where we started.

Imagine also peddles a strain of peculiarly unhelpful self-help. Want to be more creative? Well, just "listen to" your prefrontal cortex, or direct your "attention" to your right hemisphere. (Can you concentrate on different parts of your own brain? Nice trick if so.) Sometimes it helps to take a warm shower or sit in a room with blue walls; at other times you should gulp coffee or scarf Benzedrine pills like Auden. You'll be more creative when you're happy, except when you ought to be sad. Lehrer explains these apparent inconsistencies by invoking different parts of the "creative process". (Mere inspiration is not enough, he announces dramatically; you then need to edit: no benighted scrivener ever appreciated this fact before the revelatory era of neuroscience.) At another point, he offers a "parable" about how knowing less about a field of endeavour can help us think more creatively about problems in it, but we can all name a million counter-examples. (Come to think of it, there's this cat called Bob Dylan who once made a close study of the folk-music tradition …)

The larger problem for the book as a how-to guide, though, is the sheer variety of activities that Lehrer has conflated without argument as representing "creativity" or "imagination". The composition of a song or poem is just assumed to be the same sort of thing as the solving of a hoary riddle or word-puzzle by experimental volunteers in a magnetic-resonance-imaging tube, or the dreaming-up of new moves in surfing, or the copying of a German porn doll to market it as Barbie, or the invention of a new kind of mop.

What, you might ask, do mops and Barbies have to do with all this? Well, this is the kind of book that also tells inspirational business stories – for no good intellectual reason, though it might well have the happy side-effect of drumming up lucrative corporate-speaking gigs for the author. Imagine's very first sentence, trembling with executive drama, is "Procter and Gamble had a problem: it needed a new floor cleaner." So Lehrer visits 3M (repeating the oft-told story about the invention of the Post-It note), the advertising guy who penned the slogan "Just do it" for Nike (his advice: hire "weird fucks"), and the film studio Pixar, where Steve Jobs ingeniously decreed that all the toilets be put in the central atrium so people would bump into one another. This, we are assured, improves employee "performance", in the sense of "generating new ideas" for profit.

That last phrase might be a bit of a slip, though, since Lehrer doesn't really believe in "new ideas": he has bought into the philistine notion, much propagated by today's anti-copyright fanatics among others, that all artistic creation is nothing but (and thus reducible to) a mashing-up or remixing of existing artworks, so that Dylan writing a song is no different from a child on YouTube playing two grimecore tracks simultaneously. Near the end of the book, he attempts to demystify Shakespeare in this way, leaning heavily on Stephen Greenblatt and TS Eliot to rehearse the familiar point that the flowering of Shakespeare's art was dependent on the environment of Elizabethan London. He emphasises as best he can Shakespeare the mashup artist, nicker of stuff from Marlowe, Holinshed et al: "For Shakespeare," Lehrer affects to know, "the act of creation was inseparable from the act of connection."

Reaching a self-adoring climax, Lehrer writes: "For the first time in human history, it's possible to learn how the imagination actually works. Instead of relying on myth and superstition, we can think about dopamine and dissent, the right hemisphere and social networks." We can indeed think about such things, but an explanation of "how the imagination actually works" does not magically fall out of them, and hasn't done so here. And the example of Shakespeare reveals his awkward central ambivalence on the question of innate talent. Lehrer makes sceptical noises – "We tend to assume that some people are simply more creative than others," he sniffs – because he wants to sell the "uplifting moral" that we all have "a vast reservoir of untapped creativity". We probably do, but that still doesn't mean we can all be Bob Dylan. And even this book concludes that Shakespeare's "genius remains unsurpassed", a judgment that nothing in its neuroscientistic fairytale begins to explain. Something is happening here, but you don't know what it is – do you, Mr Lehrer?

Strange, because "How does it feel / To be without a home" and so forth makes a fair amount of literal sense to me. The amazing presumption of Lehrer's description, the shattering banality of its explanation, and its mystifying stupidity are all entirely characteristic of a phenomenon best branded "neuroscientism". (The term has been employed by the philosopher Colin McGinn and the critical neuroscientist Raymond Tallis, among others.) Scientism is the confidence that science can explain all aspects of human life; neuroscientism is the more specific promise that brain-scans (using the limited current technologies of fMRI and EEG) can explain the workings of the mind.

Lehrer's neuroscientistic method consists of paraphrasing brain-imaging studies, grossly inflating what can be properly inferred from them, and so purporting to explain "creativity" or "imagination". He doesn't bother to distinguish between the two – presumably Coleridge, for example, can have had nothing interesting to say on the matter. As any good neuroscientistic believer should, he regularly insults the preceding centuries of thought on his topic, dismissing it all as "completely wrong". Lehrer has a rage, indeed, to insist on the novelty of his extrapolations from the research, which usually means misrepresenting conventional wisdom. "It's commonly assumed that the best way to solve a difficult problem is to relentlessly focus," he writes, but people have always known that going for a walk or sleeping on it – or, like Archimedes, taking a bath – can help. Nor did we need to wait for colourful neuro-pictures to learn that people sometimes have good ideas during daydreams, or on holiday.

The inconvenient truth is that observing which areas of the brain light up on a screen during experiments tells us little about "how creativity works". The "right hemisphere" is here suggested to be more verbally free-associative (handling "connotation"), as opposed to the pedantically literal left hemisphere (handling "denotation").

Lehrer doesn't realise, bizarrely, that Dylan could not have written "Like a Rolling Stone" without attending to the literal meanings of words – which means, on this crude scheme, that his left hemisphere, as well as his right, must have been hard at work. So the anatomical locus of creativity is not narrowed down after all. Throughout, the author intones the jargon names for many different brain structures that, he says, are all important for creativity (even as he occasionally mumbles a confession that their "precise function" is unknown): not just the right hemisphere but also the "anterior superior temporal gyrus", the "medial prefrontal cortex", the "dorsolateral prefrontal cortex", the "neural highway" of the dopamine system, and even "the primitive midbrain". But this expansive catalogue of crucial parts merely invites us to conclude, by the end, that pretty much all of the brain has to be involved in any complex creative work. Which effectively leaves us back where we started.

Imagine also peddles a strain of peculiarly unhelpful self-help. Want to be more creative? Well, just "listen to" your prefrontal cortex, or direct your "attention" to your right hemisphere. (Can you concentrate on different parts of your own brain? Nice trick if so.) Sometimes it helps to take a warm shower or sit in a room with blue walls; at other times you should gulp coffee or scarf Benzedrine pills like Auden. You'll be more creative when you're happy, except when you ought to be sad. Lehrer explains these apparent inconsistencies by invoking different parts of the "creative process". (Mere inspiration is not enough, he announces dramatically; you then need to edit: no benighted scrivener ever appreciated this fact before the revelatory era of neuroscience.) At another point, he offers a "parable" about how knowing less about a field of endeavour can help us think more creatively about problems in it, but we can all name a million counter-examples. (Come to think of it, there's this cat called Bob Dylan who once made a close study of the folk-music tradition …)

The larger problem for the book as a how-to guide, though, is the sheer variety of activities that Lehrer has conflated without argument as representing "creativity" or "imagination". The composition of a song or poem is just assumed to be the same sort of thing as the solving of a hoary riddle or word-puzzle by experimental volunteers in a magnetic-resonance-imaging tube, or the dreaming-up of new moves in surfing, or the copying of a German porn doll to market it as Barbie, or the invention of a new kind of mop.

What, you might ask, do mops and Barbies have to do with all this? Well, this is the kind of book that also tells inspirational business stories – for no good intellectual reason, though it might well have the happy side-effect of drumming up lucrative corporate-speaking gigs for the author. Imagine's very first sentence, trembling with executive drama, is "Procter and Gamble had a problem: it needed a new floor cleaner." So Lehrer visits 3M (repeating the oft-told story about the invention of the Post-It note), the advertising guy who penned the slogan "Just do it" for Nike (his advice: hire "weird fucks"), and the film studio Pixar, where Steve Jobs ingeniously decreed that all the toilets be put in the central atrium so people would bump into one another. This, we are assured, improves employee "performance", in the sense of "generating new ideas" for profit.

That last phrase might be a bit of a slip, though, since Lehrer doesn't really believe in "new ideas": he has bought into the philistine notion, much propagated by today's anti-copyright fanatics among others, that all artistic creation is nothing but (and thus reducible to) a mashing-up or remixing of existing artworks, so that Dylan writing a song is no different from a child on YouTube playing two grimecore tracks simultaneously. Near the end of the book, he attempts to demystify Shakespeare in this way, leaning heavily on Stephen Greenblatt and TS Eliot to rehearse the familiar point that the flowering of Shakespeare's art was dependent on the environment of Elizabethan London. He emphasises as best he can Shakespeare the mashup artist, nicker of stuff from Marlowe, Holinshed et al: "For Shakespeare," Lehrer affects to know, "the act of creation was inseparable from the act of connection."

Reaching a self-adoring climax, Lehrer writes: "For the first time in human history, it's possible to learn how the imagination actually works. Instead of relying on myth and superstition, we can think about dopamine and dissent, the right hemisphere and social networks." We can indeed think about such things, but an explanation of "how the imagination actually works" does not magically fall out of them, and hasn't done so here. And the example of Shakespeare reveals his awkward central ambivalence on the question of innate talent. Lehrer makes sceptical noises – "We tend to assume that some people are simply more creative than others," he sniffs – because he wants to sell the "uplifting moral" that we all have "a vast reservoir of untapped creativity". We probably do, but that still doesn't mean we can all be Bob Dylan. And even this book concludes that Shakespeare's "genius remains unsurpassed", a judgment that nothing in its neuroscientistic fairytale begins to explain. Something is happening here, but you don't know what it is – do you, Mr Lehrer?

No comments:

Post a Comment