The fish in the pond are seeing red...

The fish in the pond are seeing red

As Bobby is fishing with Coates strong thread

(From the soon to be Published GRANNY BARKES FELL IN WOOLWORTHS.)

MISSION STATEMENT ... To celebrate where it's deserved! ... To take the Michael out of institutions and individuals where it's deserved! ... Recently I had occasion to prepare my gravestone epitaph: GENE... Educator, Novelist, Humanitarian and Humorist - TO KNOW HIM WAS TO LOVE HIM - Rest in Peace ....... But while I am still walking the earth do not hesitate to contact me at: bobbyslingshot8@gmail.com

8th January

1894 -

14th August 1941

“No one in the world can change

Truth. What we can do and should do is to seek truth and to serve it when we

have found it. The real conflict is the inner conflict. Beyond armies of

occupation and the hecatombs [e.g. the sacrifice of many victims] of

extermination camps, there are two irreconcilable enemies in the depth of every

soul: good and evil, sin and love. And what use are the victories on the

battlefield if we ourselves are defeated in our innermost personal selves?

“If anyone does not wish to

have Mary Immaculate for his Mother, he will not have Christ for his Brother.”

“Prayer is powerful beyond

limits when we turn to the Immaculata who is queen even of God's heart.”

“My aim is to institute

perpetual adoration," he said, for this is the "the most important

activity.”

“The whole world is a large

Niepokalanow where the Father is God, the mother the Immaculata, the elder

brother the Lord Jesus in all the tabernacles of the world, and the younger

brothers the people.”

“Niepokalanow is a home like

Nazareth. The Father is God the Father, the mother and mistress of the home is

the Immaculata, the firstborn son and our brother is Jesus in the most Holy

Sacrament of the altar. All the younger brothers try to imitate the elder

Brother in love and honor towards God and the Immaculata, our common parents,

and from the Immaculata they try to love the divine elder Brother, the ideal of

sanctity who deigned to come down from heaven to be incarnated in her and to

live with us in the tabernacle...”

“That night, I asked the Mother

of God what was to become of me, a Child of Faith. Then she came to me holding

two crowns, one white, the other red. She asked me if I was willing to accept

either of these crowns. The white one meant that I should persevere in purity,

and the red that I should become a martyr. I said that I would accept them

both.”

“Modern times are dominated by

Satan and will be more so in the future. The conflict with hell cannot be

engaged by men, even the most clever. The Immaculata alone has from God the

promise of victory over Satan. However, assumed into Heaven, the Mother of God now

requires our cooperation. She seeks souls who will consecrate themselves

entirely to her, who will become in her hands effective instruments for the

defeat of Satan and the spreading of God's kingdom upon earth.”

“The most deadly poison of our

time is indifference.”

“"My aim is to institute

perpetual adoration," spoke St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe, Franciscan priest

and founder of the Knights of the Immaculata. For he said that this is

"the most important activity," and "if half of the Brothers

would work, and the other half pray, this would not require too much."”

“Let us give ourselves to the

Immaculata [Mary]. Let her prepare us, let her receive Him [Jesus] in Holy

Communion. This is the manner most perfect and pleasing to the Lord Jesus and

brings great fruit to us." Because "the Immaculata knows the secret,

how to unite ourselves totally with the heart of the Lord Jesus... We do not

limit ourselves in love. We want to love the Lord Jesus with her heart, or

rather that she would love the Lord with our heart.”

Barring a startling lurch to starboard in the Empire State, Kathy Hochul, who as lieutenant governor succeeded the unlamented Andrew Cuomo on his political demise, will be chosen governor of New York in November—the first woman elected to the office once held by such worthies as John Jay, William H. Seward, Samuel J. Tilden, Grover Cleveland, Theodore Roosevelt, Al Smith, and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Students used to know that three of these men were subsequently elected president of the United States. Real students of history know that Tilden almost certainly was, too, but lost the White House in a deal to end Reconstruction after a closely contested election. An honorable man who didn’t want to enflame a country recovering from a bloody civil war, Tilden accepted his fate rather than carrying on like a five-year-old deprived of his creamsicle.

But I digress.

I’m told that Kathy Hochul is a gracious person in conversation, even with those with whom she disagrees (which would never have been said of Andrew Cuomo; but I digress again). However, she is strongly supportive of what are euphemistically called “reproductive rights,” which in fact terminate the process of reproduction (but I digress yet again). And when challenged on how she squares her pro-abortion radicalism with her Catholicism, Gov. Hochul has been known to reply, “I’m a Matthew 25 Catholic.”

This relatively new attempt to render more plausible the implausibility of “pro-choice Catholicism” by coating it with a biblical veneer takes its name from the Lord’s separation of the blessed sheep from the condemned goats: the former being those who fed the hungry, gave drink to the thirsty, clothed the naked, and welcomed the stranger; the latter being those who didn’t. The implication of declaring oneself a “Matthew 25 Catholic”—and what faux-clever theological con artist invented that sound bite, one wonders—is that supporting a broad range of social services for the poor and needy, welcoming the immigrant, and ticking all the other boxes on the Biden/Pelosi Democrats’ domestic policy agenda constitutes a moral “get out of jail free” card that can be played, first with the electorate, and then, presumably, with the Lord.

Sorry, but it won’t work.

Matthew 25 also refers, twice, to “the least of these my brethren” (Matt. 25:40, 45). And when one willfully, actively, and even aggressively promotes the killing of what are indisputably the “least” of the Lord’s brothers and sisters—those ultra-vulnerable human beings who happen not to have been born yet—it is not easy to imagine that the Lord is pleased, irrespective of one’s voting record on, say, reducing carbon emissions or raising the minimum wage. This is, after all, the same Lord who memorably said that it would be better for anyone who tempted his “little ones” to sin to have a “millstone . . . hung round his neck” and be “cast into the sea” (Luke 17:2). What will that Lord have to say about anyone who deliberately creates public policies aimed at terminating the lives of those “little ones” before birth?

The “Matthew 25 Catholic” dodge is also an implicit insult to the champions of pro-life policies who have worked for decades to provide compassionate care for women caught in the dilemma of an unwanted pregnancy and for their children, both before and after birth. Does “Matthew 25 Catholicism” include generous public support for pre-natal care in crisis pregnancy centers, well-child pediatric services, and job-training programs for single moms who carry their children to term but who’ve been abandoned by the kind of male irresponsibility the abortion license has facilitated? I hope it does. But I am waiting for the first “Matthew 25 Catholic” public official to make a big deal about that, rather than burning incense to the Moloch of NARAL Pro-Choice America in the aftermath of the heroic Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision of this past June 24.

I have no window into the soul of those Catholic public officials who declare themselves “Matthew 25 Catholics,” as a counter to the suggestion that their Catholicism is defective because of their support of the abortion license. They may be sincere, but ill-catechized. They may have been advised by unscrupulous progressive clergy, or by left-leaning Catholic political activists for whom the pro-life position has always been an embarrassment. But whatever their subjective moral condition, they are using biblical imagery as political cover for the indefensible. And they should stop.

I like to think that at least some of them, the ones who actually take Matthew 25 with the gravity it deserves, are better than that.

George Weigel is Distinguished Senior Fellow of Washington, D.C.’s Ethics and Public Policy Center, where he holds the William E. Simon Chair in Catholic Studies.

First Things depends on its subscribers and supporters. Join the conversation and make a contribution today.

Click here to make a donation.

Click here to subscribe to First Things.

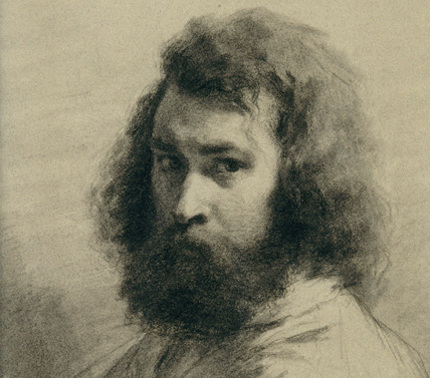

THE ANGELUS ... A timeless classic by Millet

Millet was born at Grouchy (Manche) and was a pupil of Paul Delaroche in Paris by 1837. For some years he painted chiefly idylls in imitation of 18th-century French painters. Becoming, like Honoré Daumier, increasingly moved by the spectacle of social injustice, Millet turned to peasant subjects and won his first popular success at the Salon of 1848 with 'The Winnower'. From the following year he was chiefly active at Barbizon and associated with the Barbizon school of landscape painters.

His work was influenced by Dutch paintings of the 17th century and by the work of Jean-Siméon Chardin, and was influential in Holland on Jozef Israëls and on the early style of Vincent Van Gogh.

Blessed Carlo Acutis is set to become the first millennial saint. This

isn’t the first time the Catholic Church has canonized children.

The

body of Carlo Acutis

(THE CONVERSATION) On Oct. 10, 2020,

a young Italian named Carlo Acutis was beatified at

a special Mass in the city of Assisi, putting the late teenager just one step

away from sainthood. It allows Catholics to venerate him as “Blessed Carlo

Acutis.”

Acutis died of leukemia in 2006, at the

age of 15. Like other boys his age, he was avidly interested in computers,

video games and the internet. He was also a devout Catholic who went to Mass

daily and persuaded his mother as well to be a regular attendee. One of his pet

projects was designing a webpage listing miracles across the globe associated

with the bread and wine consecrated at Mass, believed by Catholics to be the

body and blood of Christ.

ADVERTISEMENT

After his death, townspeople began to attribute miracles to his

intercession, including the birth of twins to his own mother four

years after his death. His case was submitted to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, one of

the offices that make up the papal administrative structure – the Curia – of

the Catholic Church. It initiated the process of his official canonization in

the Roman Catholic Church.

To non-Catholics, bestowing potential

sainthood on one who died so young might seem puzzling. As a scholar of medieval

liturgy and culture, I know that there has been a long history of

including children among the saints approved for official recognition and

veneration.

Who becomes a saint

ADVERTISEMENT

For the first thousand years of

Western Christian history, there was no formal process in Rome for declaring

deceased persons as saints. In antiquity, Christians who became martyrs or

imprisoned as confessors during persecutions were venerated after their deaths because

of the strength of their beliefs. They were considered more perfect Christians

because they chose to die rather than give up their faith.

Because of this, the martyrs were

believed to be closely united with Christ in heaven. Individuals would pray at

their tombs, asking the martyrs to intercede with Christ for help with

spiritual or material problems, like healing from an illness.

Miracles were attributed to their

intervention, since Christians believed that the tombs

of the martyrs were holy places where they could access the

healing power of God’s grace.

ADVERTISEMENT

After Christianity spread throughout

Europe, other Christians who led lives of unusual holiness were also venerated

in the same way. These included bishops and priests, monks and nuns and other

laypeople of exceptional virtue.

All of these saints were venerated

locally, with the approval of the local bishop. However, the first saint to

be officially canonized by a pope – Pope

John XV – was St. Ulrich of Augsburg. Ulrich had served as the bishop of

Augsburg for almost 50 years, building churches, revitalizing the clergy, and

helping the residents resist a siege by invaders.

His canonization took place in A.D.

993 after the local bishop requested that the pope make the declaration.

ADVERTISEMENT

From that time on popes would preside

over the canonization process, and a set procedure for investigating potential

candidates was established as part of the papal bureaucracy in Rome. After

the Second Vatican Council, held from 1962 to

1965, called for a new vision of the church’s role in the world of the 20th

century, the process was updated.

Today, proposed candidates are given

the title “Servant of God.” If they were martyred or killed “in hatred of the

faith,” they move to the next-to-last stage – beatification – and receive the

title “Blessed.” Non-martyrs, if shown to have lived lives of “heroic virtue,”

are given the title “Venerable Servant of God.”

Proceeding to beatification requires

clear evidence of a miracle, often a healing, that is understood to have

resulted from a direct prayer to the Servant of God asking for help. Claims of

healing miracles are closely examined by a panel of medical

experts. A second miracle is required for canonization.

Why child saints?

Over the centuries, several children

have been proclaimed “Blessed” or “Saint.”

One group of child saints was

venerated from late antiquity onward because of their mention in the

gospels: the Holy Innocents. In the Gospel of Matthew, King Herod, threatened by

rumors of the birth of a new king, sends soldiers to Bethlehem to kill all male

infants and toddlers. These children became known as the Holy Innocents.

Because of their connection with the

story of the birth of Jesus, sometime in the fifth century the commemoration of

the Holy Innocents was set during Christmas week, Dec. 28 in the Western

Church. This day is observed by all Catholics even today.

Sometimes child saints have been

canonized as part of a larger group of martyrs. For example, among those

martyred in China for their Christian faith are 120 Chinese Catholics killed between 1648 and 1930.

Members were recognized for their unswerving dedication to the Catholic faith

during several periods of intense persecution.

They were canonized by Pope St. John Paul II in 2000. In his homily on that day, the pope made

special mention of the heroic deaths of two of them: 14-year-old Anna Wang and 18-year-old Chi Zhuzi, both of whom died in 1900.

Other child saints were canonized as

individuals. One modern example is Maria Goretti, an Italian peasant girl

murdered in 1902. Only 11 years old, she was alone at the home her impoverished

family shared with another family when she was attacked by the young adult son

of that family.

He attempted to rape her and stabbed

her when she fought him off. Maria died the next day in a hospital after

stating that she forgave her attacker and prayed that God might forgive him,

too.

News of this spread quickly across

Italy, and stories of miracles followed soon after. Maria was canonized in 1950 and quickly

became a popular patron saint for young girls.

A few child saints were deemed to

have demonstrated heroic virtue in other ways. In 1917, three peasant children

from the town of Fatima in Portugal claimed to have received visions of the

Blessed Virgin Mary. News of this spread widely, and the location became a

popular pilgrimage site. The oldest child, Lucia, became a nun and lived into

her 90s; her cause for sainthood is still in process.

However, her two cousins, Francisco

and Jacinta Marto, died young of complications from the Spanish flu: Francisco

in 1918 at the age of 10, and Jacinta in 1919, age 9. The two were beatified in 2000 by Pope St. John Paul II and canonized by Pope Francis in 2017.

They were the first child

saints who were not martyrs. It was their “heroism”

and “life of prayer” that was considered to be holy. There were other child

saints too who were canonized for reasons other than being martyrs,

yet led lives considered exemplary.

But there were also those who were

dropped from the official list of saints because of details that were later

revealed. One such case was of a 2-year-old Christian boy Simon from Trent, Italy,

whose body was found in the cellar of a Jewish family in 1475. Simon’s body was

on display and miracles were attributed to him. It was 300 years later that the

Jews of Trent were cleared of murder charges. In 1965 his name was removed from

the Calendar of Saints by Pope Paul VI.

Nonetheless, this long history shows

that sanctity is not limited to adults who lived in the distant past. In the

eyes of the Catholic Church, an ordinary teenager in the 21st century too can

be worthy of veneration.

The Sins of the High

Court’s Supreme Catholics

The overturn of Roe v. Wade is part of ultra-conservatives’ long history

of rejecting Galileo, Darwin, and Americanism.

(No it isn't!) Gene

August 19,

Five Catholics on the Supreme Court are undermining not only basic

elements of American democracy but also the essential spirit of Catholicism’s

great twentieth-century renewal.Photograph by Jabin Botsford / The

Washington Post / Getty

As part of the Vatican’s war on “modernism” in 1899, Pope Leo XIII

condemned as heresy the set of principles known as “Americanism.” But, by 1965,

at the Second Vatican Council, the Church had begun to embrace such supposedly

odious ideas: pluralism, the separation of church and state, the primacy of

conscience, the preference of experience over dogma, and—for that

matter—freedom of the press. This was a historic reversal of the Church’s

panicked nineteenth-century repudiation of, in Pope Leo’s words, “modern

popular theories and methods.”

Now five Catholic Justices on the Supreme Court are reversing the Church’s reversal. (Neil Gorsuch, who is now an Episcopalian but was raised and educated as a Catholic, joined his five colleagues in overturning Roe v. Wade.) These Justices are undermining not only basic elements of American democracy, such as the “wall of separation,” but also the essential spirit of Catholicism’s great twentieth-century renewal. It’s no secret, of course, that the Second Vatican Council, or Vatican II, which had been summoned by the renewal-minded Pope John XXIII, generated a powerful pushback from traditionalists within the Church. The reforms set in motion by the council—composed of more than two thousand Catholic bishops, who met in St. Peter’s Basilica in four sessions, between 1962 to 1965—upended sacrosanct doctrines and traditions, ranging from the language used in Mass to the idea of “no salvation outside the Church,” to the repudiation of the ancient anti-Semitic Christ-killer slander. Indeed, Vatican II took a step away from monarchy and toward democracy.

Bottom of Form

An ultra-conservative blowback ensued, defining the

papacies of Paul VI, John Paul I, John Paul II, and Benedict XVI, and it proved

to be obsessed, above all, with issues related to sexuality and the place of women. This focus emerged even

before Vatican II ended, when a nervous Paul VI, who had succeeded Pope John

after his death, in 1963, made an extraordinary intervention in the proceedings

by forbidding the Council from taking on the question of contraception. Paul’s dictum

signalled what was to come when, in 1968, he defied a consensus that was

emerging among Catholics—even among the bishops—to accept birth control, and

formally condemned it in his encyclical “Humanae Vitae” (“Of Human Life”). As

if foreseeing that clash, during the council’s deliberations, one of its most

powerful leaders, Cardinal Leo Joseph Suenens, of Belgium, protested the Pope’s

intervention by rising in St. Peter’s and saying, “I beg you, my brother

bishops, let us avoid a new Galileo affair. One is enough for the

Church.”

But a new Galileo affair is what the Church got.

This one, though, is about the relationship not of the Earth to the Sun but of

women to men. Moving from condemnation of birth control to a new absolutism on

the question of abortion, a backpedalling succession of increasingly

reactionary prelates ignored the Belgian cardinal’s warning. Over the last

several decades, the Church hierarchy effectively turned the female body into a

bulwark against the changes that the Vatican II generation had embraced.

The elevation of the issue of abortion as the

be-all and end-all of Catholic orthodoxy echoes the anti-modern battles that

the nineteenth-century Church fought. A pair of dates tells the story. In 1859,

Charles Darwin published “On the Origin of Species,”

and the idea of biological evolution began to grip the Western imagination. In

1869, Pope Pius IX, in his pronouncement “Apostolicae Sedis,” forbade the

abortion of a pregnancy from the moment of conception forward—an effective

locating of human “ensoulment” at the joining of the ovum and sperm, an all but

explicit rejection of evolutionary theory.

Yet dynamic change was coming to be seen as the rule of life, transforming ideas not only of how humanity came into being but of how individual humans do. Traditional ways of reading the Genesis story, of course, posed an immediate obstacle to any substantial overturning of assumptions about human origins. But, with Darwin as a starting point, many religious believers, including Catholics, proved capable of viewing Genesis and its seven-day creation calendar as metaphor, and of seeing that God’s creative act had, in fact, unfolded across many eons. Still, the idea that people had been created in a single moment of miraculous divine intervention proved tenacious. Michelangelo’s image of God’s finger touching Adam’s, endowing the creature with the instantaneous gift of human life, seemed fixed in the Western consciousness

However, despite Pius IX’s nineteenth-century

rejection of Darwin’s evolutionary theory, the idea that ensoulment unfolds

during the process of fetal development, at some indeterminate point weeks or

months after conception, more or less meshes with long-held

understandings—expressed by writers including Aristotle and St. Jerome, in the

ancient world, and St. Thomas Aquinas, in the Middle Ages. But the great

purpose of the Genesis story is not necessarily to explain life but to account

for human suffering: its most consequential assertion is that the inevitable

miseries of human existence are the fault of Eve, who serves as a stand-in for

all women. It was Eve who supposedly yielded to the devil’s temptation, and, in

turn, tempted Adam, thereby dooming both themselves and all their progeny.

This story gives us the concept of “original sin”—a

phrase that does not appear in the Bible—and represents the ultimate form of

fraudulent originalism. To read the Book of Genesis as a literal account of how

the world and human life began is pure fundamentalism, and it poses a danger to

the rule of reason on which the common good depends. So, too, do ahistorical

readings of the U.S. Constitution. “Originalism is a legal philosophy of

stasis, which reifies a historical moment,” the writer Siri Hustvedt points out in

a recent piece for Literary Hub. But such historical fundamentalism, she argues,

also applies to attitudes toward the creation of the individual: “The reduction

of a dynamic, metamorphosing conceptus to a single abstract entity—‘the

unborn’—denies both time and change.” And that denial has led to the legal, medical, economic, and personal calamities facing a post-Dobbs America, with women experiencing the

brunt of the threat.

The Catholic experience of such fundamentalism is a

warning. Back in the fourth century, St. Augustine, whose influence on theology

surpasses even that of Aquinas, centered the Adam and Eve narrative on sex. The

forbidden fruit, he believed, was the pleasure that the first couple took in

sexual arousal. From then on, the sanctioned Catholic imagination was radically

corrupted by fear of and contempt for autonomous female sexuality. The Church’s

unfettered campaign against women (elevating virginity, requiring female

subservience in marriage and at the altar, restricting women’s ability to

control their own bodies) was launched. Now it has been joined by the Supreme

Court’s Catholic majority.

For decades, that campaign has been faltering among

Catholics in the United States. Shortly after Pope Paul VI’s condemnation of birth

control, in 1968, a group of ten priests and theologians at the Catholic

University of America, in Washington, D.C., resoundingly denounced that papal

teaching. It was, they said, “based on an inadequate concept of natural law”

and on “a static world view which downplays the historical and evolutionary

character of humanity.” And most American Catholics agreed, demonstrating that

a transformation of attitudes about sex and women had already taken root among

them; in the years since, polls have shown that a large majority of

Catholic women use birth control. Declining birth rates among Catholics,

mirroring those of the broader U.S. population, confirm what the faithful

thought of that papal pronouncement.

Now that the Supreme Court, with an extreme originalist misreading of the Constitution, has

revoked the constitutional right to obtain an abortion, the renewed political

and religious tensions surrounding the issue can be clarifying, perhaps

especially for Catholics. They can begin to reclaim the evolutionary character

of their own history and beliefs, as well as of the understanding of when

personhood begins. Indeed, many Catholics already do this, with

leading Catholic politicians, for example, Joe Biden and Nancy Pelosi,

affirming abortion rights. They may cloak that affirmation in language about

not wanting to impose their own religious views on others, but this really amounts

to an implicit rejection of the idea that human life—and human rights—begins at

conception. That rejection should be made explicit.

Freedom of conscience, historical consciousness,

the rights of other people to be other people, the idea that sacredness is

everywhere, not just in religion—such are aspects of the onetime heresy,

Americanism. Catholics in the United States can finally and openly affirm these

views. Americanism helped bring about the renewal of the Church, when the

Second Vatican Council embraced those very principles, the foundation of

liberal democracy.

With the threat to the Church’s unfinished renewal

now coming from Catholic Justices, that renewal, with its underlying American

ideals, is worth retrieving and advancing, especially as a way to challenge the

anti-abortion Catholic legislators who are taking what they perceive as moral

instruction from a throwback Supreme Court. Indeed, the defiance by legions of

Catholic women of Pope Paul VI’s condemnation of birth control can itself be a

model of conscientious objection. Birth control and abortion are not the same

thing, but the autonomy of women, the primacy of conscience, and the rejection

of overreaching male-supremacist authority add up to an American refusal to

obey draconian new laws that claim to defend human life yet do the

opposite. ♦

Mid-Term Break