Walter Brueggemann: How to read the Bible on homosexuality

What Scripture has to say

It is easy enough to see at first glance why LGBTQ people, and those who stand in solidarity with them, look askance at the Bible. After all, the two most cited biblical texts on the subject are the following, from the old purity codes of ancient Israel:

You shall not lie with a male as with a woman; it is an abomination (Lev. 18:22).

If a man lies with a male as with a woman, both of them have committed an abomination; they shall be put to death; their blood is upon them (Lev. 20:13).

There they are. There is no way around them; there is no ambiguity in them. They are, moreover, seconded by another verse that occurs in a list of exclusions from the holy people of God:

No one whose testicles are crushed or whose penis is cut off shall be admitted to the assembly of the Lord (Deut. 23:1).

This text apparently concerns those who had willingly become eunuchs in order to serve in foreign courts. For those who want it simple and clear and clean, these texts will serve well. They seem, moreover, to be echoed in this famous passage from the Apostle Paul:

They exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling a mortal human being or birds or four-footed animals or reptiles. Therefore God gave them up in the lusts of their hearts to impurity, to the degrading of their bodies among themselves, because they exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator, who is blessed forever! Amen.

For this reason God gave them up to degrading passions. Their women exchanged natural intercourse for unnatural, and in the same way also the men, giving up natural intercourse with women, were consumed with passion for one another. Men committed shameless acts with men and received in their own persons the due penalty for their error (Rom. 1:23-27).

Paul’s intention here is not fully clear, but he wants to name the most extreme affront of the Gentiles before the creator God, and Paul takes disordered sexual relations as the ultimate affront. This indictment is not as clear as those in the tradition of Leviticus, but it does serve as an echo of those texts. It is impossible to explain away these texts.

Given these most frequently cited texts (that we may designate as texts of rigor), how may we understand the Bible given a cultural circumstance that is very different from that assumed by and reflected in these old traditions?

Well, start with the awareness that the Bible does not speak with a single voice on any topic. Inspired by God as it is, all sorts of persons have a say in the complexity of Scripture, and we are under mandate to listen, as best we can, to all of its voices.

On the question of gender equity and inclusiveness, consider the following to be set alongside the most frequently cited texts. We may designate these texts as texts of welcome. Thus, the Bible permits very different voices to speak that seem to contradict those texts cited above. Therefore, the prophetic poetry of Isaiah 56:3-8 has been taken to be an exact refutation of the prohibition in Deuteronomy 23:1:

Do not let the foreigner joined to the Lord say, “The Lord will surely separate me from his people”; and do not let the eunuch say, “I am just a dry tree.” For thus says the Lord: To the eunuchs who keep my sabbaths, who choose the things that please me and hold fast my covenant, I will give, in my house and within my walls, a monument and a name better than sons and daughters; I will give them an everlasting name that shall not be cut off … for my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples. Thus says the Lord God, who gathers the outcasts of Israel, I will gather others to them besides those already gathered (Is. 56:3-8).

This text issues a grand welcome to those who have been excluded, so that all are gathered in by this generous gathering God. The temple is for “all peoples,” not just the ones who have kept the purity codes.

Beyond this text, we may notice other texts that are tilted toward the inclusion of all persons without asking about their qualifications, or measuring up the costs that have been articulated by those in control. Jesus issues a welcoming summons to all those who are weary and heavy laden:

Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light (Mt. 11:28-30).

No qualification, no exclusion. Jesus is on the side of those who are “worn out.” They may be “worn out” by being lower-class people who do all the heavy lifting, or it may be those who are “worn out” by the heavy demands of Torah, imposed by those who make the Torah filled with judgment and exclusion.

Since Jesus mentions his “yoke,” he contrasts his simple requirements with the heavy demands that are imposed on the community by teachers of rigor. Jesus’ quarrel is not with the Torah, but with Torah interpretation that had become, in his time, excessively demanding and restrictive. The burden of discipleship to Jesus is easy, contrasted to the more rigorous teaching of some of his contemporaries. Indeed, they had made the Torah, in his time, exhausting, specializing in trivialities while disregarding the neighborly accents of justice, mercy and faithfulness (cf. Mt. 23:23).

A text in Paul (unlike that of Romans 1) echoes a baptismal formula in which all are welcome without distinction:

There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male or female; for all of you are one in Christ (Gal. 3:28).

No ethnic distinctions, no class distinctions and no gender distinctions. None of that makes any difference “in Christ,” that is, in the church. We are all one, and we all may be one. Paul has become impatient with his friends in the churches in Galatia who have tried to order the church according to the rigors of an exclusionary Torah. In response, he issues a welcome that overrides all the distinctions that they may have preferred to make.

Start with the awareness that the Bible does not speak with a single voice on any topic. Inspired by God as it is, all sorts of persons have a say in the complexity of Scripture, and we are under mandate to listen, as best we can, to all of its voices.

Finally, among the texts I will cite is the remarkable narrative of Acts of the Apostles 10. The Apostle Peter has raised objections to eating food that, according to the purity codes, is unclean; thus, he adheres to the rigor of the priestly codes, not unlike the ones we have seen in Leviticus. His objection, however, is countered by “a voice” that he takes to be the voice of the Lord. Three times that voice came to Peter amid his vigorous objection:

What God has made clean, you must not call profane (Acts 10:15).

The voice contradicts the old purity codes! From this, Peter is able to enter into new associations in the church. He declares:

You yourselves know that it is unlawful for Jews to associate with or to visit a Gentile; but God has shown me that I should not call anyone profane or unclean (Acts 10:28).

And from this Peter further deduces:

I truly understand that God shows no partiality, but in every nation anyone who fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him (v. 34).

This is a remarkable moment in the life of Peter and in the life of the church, for it makes clear that the social ordering governed by Christ is beyond the bounds of the rigors of the old exclusivism.

I take the texts I have cited to be a fair representation of the very different voices that sound in Scripture. It is impossible to harmonize the mandates to exclusion in Leviticus 18:22, 20:13 and Deuteronomy 23:1 with the welcome stance of Isaiah 56, Matthew 11:28-30, Galatians 3:28 and Acts 10.

Other texts might be cited as well, but these are typical and representative. As often happens in Scripture, we are left with texts in deep tension, if not in contradiction, with each other. The work of reading the Bible responsibly is the process of adjudicating these texts that will not be fit together.

The reason the Bible seems to speak “in one voice” concerning matters that pertain to LGBTQ persons is that the loud voices most often cite only one set of texts, to the determined disregard of the texts that offer a counter-position. But our serious reading does not allow such a disregard, so that we must have all of the texts in our purview.

The process of the adjudication of biblical texts that do not readily fit together is the work of interpretation. I have termed it “emancipatory work,” and I will hope to show why this is so. Every reading of the Bible—no exceptions—is an act of interpretation. There are no “innocent” or “objective” readings, no matter how sure and absolute they may sound.

Everyone is engaged in interpretation, so that one must pay attention to how we do interpretation. In what follows, I will identify five things I have learned concerning interpretation, learnings that I hope will be useful as we read the Bible, responsibly, around the crisis of gender identity in our culture.

The reason the Bible seems to speak “in one voice” concerning matters that pertain to LGBTQ persons is that the loud voices most often cite only one set of texts, to the determined disregard of the texts that offer a counter-position.

1. All interpretation filters the text through the interpreter’s life.

All interpretation filters the text through life experience of the interpreter. The matter is inescapable and cannot be avoided. The result, of course, is that with a little effort, one can prove anything in the Bible. It is immensely useful to recognize this filtering process. More specifically, I suggest that we can identify three layers of personhood that likely operate for us in doing interpretation.

First, we read the text according to our vested interests. Sometimes we are aware of our vested interests, sometimes we are not. It is not difficult to see this process at work concerning gender issues in the Bible. Second, beneath our vested interests, we read the Bible through the lens of our fears that are sometimes powerful, even if unacknowledged. Third, at bottom, beneath our vested interests and our fears, I believe we read the Bible through our hurts that we often keep hidden not only from others, but from ourselves as well.

The defining power of our vested interests, our fears and our hurts makes our reading lens seem to us sure and reliable. We pretend that we do not read in this way, but it is useful that we have as much self-critical awareness as possible. Clearly, the matter is urgent for our adjudication of the texts I have cited.

It is not difficult to imagine how a certain set of vested interests, fears and hurts might lead to an embrace of the insistences of texts of rigor that I have cited. Conversely, it is not difficult to see how LGBTQ persons and their allies operate with a different set of filters, and so gravitate to the texts of welcome.

2. Context inescapably looms large in interpretation.

There are no texts without contexts and there are no interpreters without context that positions one to read in a distinct way. Thus, the purity codes of Leviticus reflect a social context in which a community under intense pressure sought to delineate, in a clear way, its membership, purpose and boundaries.

The text from Isaiah 56 has as its context the intense struggle, upon return from exile, to delineate the character and quality of the restored community of Israel. One cannot read Isaiah 56 without reference to the opponents of its position in the more rigorous texts, for example, in Ezekiel. And the texts from Acts and Galatians concern a church coming to terms with the radicality of the graciousness of the Gospel, a radicality rooted in Judaism that had implications for the church’s rich appropriation of its Jewish inheritance.

Each of us, as interpreter, has a specific context. But we can say something quite general about our shared interpretive context. It is evident that Western culture (and our place in it) is at a decisive point wherein we are leaving behind many old, long-established patterns of power and meaning, and we are observing the emergence of new patterns of power and meaning. It is not difficult to see our moment as an instance anticipated by the prophetic poet:

Do not remember the former things, or consider the things of old. I am about to do a new thing; now it springs forth, do you not perceive it? (Is. 43:18-19)

The “old things” among us have long been organized around white male power, with its tacit, strong assumption of heterosexuality, plus a strong accent on American domination. The “new thing” emerging among us is a multiethnic, multicultural, multiracial, multi-gendered culture in which old privileges and positions of power are placed in deep jeopardy.

We can see how our current politico-cultural struggles (down to the local school board) have to do with resisting what is new and protecting and maintaining what is old or, conversely, welcoming what is new with a ready abandonment of what is old.

If this formulation from Isaiah roughly fits our circumstance in Western culture, then we can see that the texts of welcome are appropriate to our “new thing,” while the texts of rigor function as a defense of what is old. In many specific ways our cultural conflicts—and the decisions we must make—reverberate with the big issue of God’s coming newness.

In the rhetoric of Jesus, this new arrival may approximate among us the “coming of the kingdom of God,” except that the coming kingdom is never fully here but is only “at hand,” and we must not overestimate the arrival of newness. It is inescapable that we do our interpretive work in a context that is, in general ways, impacted by and shaped through this struggle for what is old and what is new.

3. Texts do not come at us one at a time

Texts do not come at us one at a time, ad seriatim, but always in clusters through a trajectory of interpretation. Thus, it may be correct to say that our several church “denominations” are, importantly, trajectories of interpretation. Location in such a trajectory is important, both because it imposes restraints upon us, and because it invites bold imagination in the context of the trajectory.

We do not, for the most part, do our interpretation in a vacuum. Rather we are “surrounded by a cloud of [nameable] witnesses” who are present with us as we do our interpretive work (Heb. 12:1).

For now, I worship in a United Methodist congregation, and it is easy enough to see the good impact of the interpretive trajectory of Methodism. Rooted largely in Paul’s witness concerning God’s grace, the specific Methodist dialect, mediated through Pelagius and then Arminius, evokes an accent on the “good works” of the church community in response to God’s goodness.

That tradition, of course, passed through and was shaped by the wise, knowing hands of John Wesley, and we may say that, at present, it reflects the general perspective of the World Council of Churches with its acute accent on social justice. The interpretive work of a member of this congregation is happily and inevitably informed by this lively tradition.

It is not different with other interpretive trajectories that are variously housed in other denominational settings. We are situated in such interpretive trajectories that allow for both innovation and continuity. Each trajectory provides for its members some guardrails for interpretation that we may not run too far afield, but that also is a matter of adjudication—quite often a matter of deeply contested adjudication.

4. We are in a “crisis of the other”

We are, for now, deeply situated in a crisis of the other. We face folk who are quite unlike us, and their presence among us is inescapable. We are no longer able to live our lives in a homogenous community of culture-related “look alikes.” There are, to be sure, many reasons for this new social reality: global trade, easier mobility, electronic communication and mass migrations among them.

We are thus required to come to terms with the “other,” who disturbs our reductionist management of life through sameness. We have a fairly simple choice that can refer to the other as a threat, a rival enemy, a competitor, or we may take the other as a neighbor. The facts on the ground are always complex, but the simple human realities with each other are not so complex.

While the matter is pressing and acute in our time, this is not a new challenge to us. The Bible provides ongoing evidence about the emergency of coming to terms with the other. Thus, the land settlements in the Book of Joshua brought Israel face-to-face with the Canaanites, a confrontation that was mixed and tended toward violence (Judg. 1).

The struggle to maintain the identity and the “purity” of the holy people of God was always a matter of dispute and contention. In the New Testament, the long, hard process of coming to terms with “Gentiles” was a major preoccupation of the early church, and a defining issue among the Apostles. We are able to see in the Book of Acts that over time, the early church reached a readiness to allow non-Jews into the community of faith.

The new thing emerging among us is a multiethnic, multicultural, multiracial, multi-gendered culture in which old privileges and positions of power are placed in deep jeopardy.

And now among us the continuing arrival of many “new peoples” is an important challenge. There is no doubt that the texts of rigor and the texts of welcome offer different stances in the affirmation or negation of the other. And certainly among the “not like us” folk are LGBTQ persons, who readily violate the old canons of conformity and sameness. Such persons are among those who easily qualify as “other,” but they are no more and no less a challenge than many other “others” among us.

And so the church is always re-deciding about the other, for we know that the “other”—LBGTQ persons among us—are not going to go away. Thus, we are required to come to terms with them. The trajectory of the texts of welcome is that they are to be seen as neighbors who are welcomed to the resources of the community and invited to make contributions to the common wellbeing of the community. By no stretch of any imagination can it be the truth of the Gospel that such “others” as LGBTQ persons are unwelcome in the community.

In that community, there are no second-class citizens. We had to learn that concerning people of color and concerning women. And now, the time has come to face the same gospel reality about LGBTQ persons as others are welcomed as first-class citizens in the community of faithfulness and justice. We learn that the other is not an unacceptable danger and that the other is not required to give up “otherness” in order to belong fully to the community. We in the community of faith, as in the Old and New Testaments, are always called to respond to the other as a neighbor who belongs with “us,” even as “we” belong with and for the “other.”

5. The Gospel is not to be confused with the Bible.

The Gospel is not to be confused with or identified with the Bible. The Bible contains all sorts of voices that are inimical to the good news of God’s love, mercy and justice. Thus, “biblicism” is a dangerous threat to the faith of the church, because it allows into our thinking claims that are contradictory to the news of the Gospel. The Gospel, unlike the Bible, is unambiguous about God’s deep love for all peoples. And where the Bible contradicts that news, as in the texts of rigor, these texts are to be seen as “beyond the pale” of gospel attentiveness.

Because:

our interpretation is filtered through our close experience,

our context calls for an embrace of God’s newness,

our interpretive trajectory is bent toward justice and mercy,

our faith calls us to the embrace of the other and

our hope is in the God of the gospel and in no other,

the full acceptance and embrace of LGBTQ persons follows as a clear mandate of the Gospel in our time. Claims to the contrary are contradictions of the truth of the Gospel on all the counts indicated above.

These several learnings about the interpretive process help us grow in faith:

- We are warned about the subjectivity of our interpretive inclinations;

- we are invited in our context to receive and welcome God’s newness;

- we can identify our interpretive trajectory as one bent toward justice and mercy;

- we may acknowledge the “other” as a neighbor;

- we can trust the gospel in its critical stance concerning the Bible.

All of these angles of interpretation, taken together, authorize a sign for LGBTQ persons: Welcome!

Welcome to the neighborhood! Welcome to the gifts of the community! Welcome to the work of the community! Welcome to the continuing emancipatory work of interpretation!

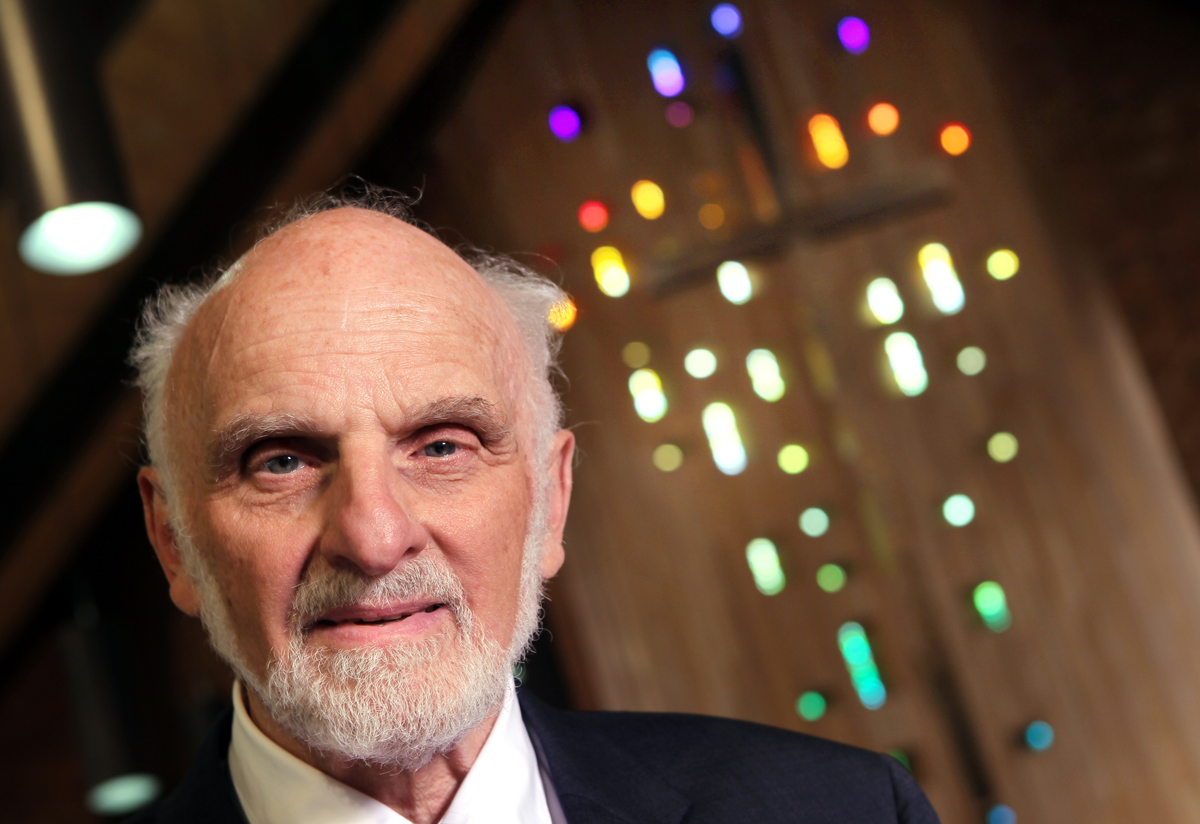

Walter Brueggemann

Walter Brueggemann is one of the world's leading Old Testament scholars and the author of nearly 150 books. From 1986 to 2003, he was the William Marcellus McPheeters Professor of Old Testament at the Columbia Theological Seminary in Decatur, Ga.