Monsignor Óscar Romero: His Lesson for Freedom of Religion or Belief

A speech at the webinar “The Right to Truth on Human Rights Violations: The Tai Ji Men Case in Comparative Perspective” held on March 24, 2021.

by Massimo Introvigne

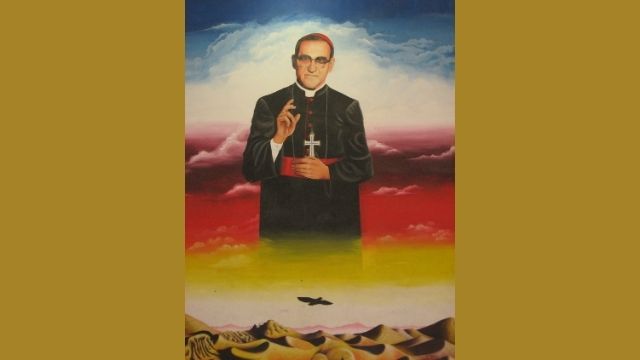

March 24 is the International Day for the Right to the Truth Concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims, a long name for a day coming from the sacrifice of a single man. The International Day was instituted by the United Nations in 2010, and is commemorated every year. March 24, 1980 is when Catholic Archbishop Óscar Arnulfo Romero (1917–1980) was assassinated in San Salvador, El Salvador.

Born in Eastern El Salvador in 1917, Romero was a bright student and seminarian, and was sent to study at the Gregorian University in Rome before being ordained a Catholic priest in 1942. He was appointed an Auxiliary Bishop of San Salvador in 1970, Bishop of Santiago de Maria in 1974, and Archbishop of El Salvador in 1977. Romero was theologically conservative (the day he was assassinated, he had just attended a retreat of Opus Dei, a Catholic institution generally regarded as critical of liberal theology), but at the same time he raised his voice against the economic injustice, the humiliation of the poor, and the human rights violations perpetrated by the military government and the even more extreme right-wing militias, one of which was responsible for his assassination.

We should understand the time in which Romero was assassinated. I never met him, but visited Central America repeatedly and met many who knew him well. He was assassinated in the Cold War years, and his sacrifice was initially politicized. For instance, American activist Noam Chomsky and others criticized the Catholic Church because, when celebrating “modern martyrs,” it allegedly insisted more on the Polish priest Jerzy Popiełuszko (1947–1984), killed by a pro-Soviet Communist regime, than on Romero, who had been killed by militias that were right-wing and pro-American. In fact, eventually the Catholic Church proclaimed Romero a saint in 2018, while Popiełuszko had been beatified in 2010 and is still one step before sainthood.

Biographers have also recognized that Romero was equally critical of Communist and right-wing dictators. When somebody told him that there were only two religions, the religion of the rich and the religion of the poor, Romero, with all his love and advocacy for the poor, answered that such a statement came from the religion of the demagogues. In fact, as he said in a famous speech, Romero rather distinguished between governments respecting human rights, justice, and conscience and those who denied them.

The real lesson of Romero is that there are no legitimate reasons to deny human rights. His government in his time believed that human rights could be somewhat “suspended” to protect El Salvador from Communist influences coming from the Soviet Union via Cuba and Nicaragua. Romero was certainly not an admirer of the Soviet Union, but believed there should be other ways of protecting his country, not suspending human rights. He taught us that those who advocate for human rights are “for” their countries, not “against” them. This has been recognized in El Salvador, and today those who fly to its capital arrive at Saint Óscar Arnulfo Romero International Airport.

On the International Day originating from Romero’s sacrifice, we reflect on freedom of religion or belief and the Tai Ji Men case, in Taiwan and in comparative perspective. Romero wrote that religious persecution happens because “truth is always persecuted,” and that God blesses those who protest and fight for freedom. But they should know they should suffer, because “pain is the money that buys freedom.”

Romero’s key teaching, that there is no reason good enough to justify the violation of human rights, is relevant for both religious liberty and the Tai Ji Men case. There are governments that claim that limiting religious liberty is necessary to protect social stability or the harmony of the country. Romero’s message is that this is not a valid justification. Human rights protection defines what a legitimate social stability is, rather than the other way around.

In the Tai Ji Men case, it was believed in 1996 that cracking down on some spiritual movements would protect Taiwan’s political order. Romero taught us that political orders cannot be protected at the expenses of human rights. And some believe today that those who were guilty of illegal acts in the persecution of Tai Ji Men should not be punished, to protect the image and the credibility of the state bureaucracy and Taiwan’ National Tax Bureau. Romero would answer that reputation of government officials and institution is less important than human rights. In fact, it is the respect of human rights and the implementation of social justice that produce a government’s good reputation.

Romero is also relevant for our topic as he emphasized the right to be told the truth and the right to protest. For defending these rights, he eventually paid the ultimate price of his life. Tai Ji Men dizi who passionately protest for truth, conscience, and justice may find in Romero a model. Their pursuit of truth, upholding justice, distinction between right and wrong, and adherence to conscience are also the spirit that Tai Ji Men has been promoting. As a menpai of self-cultivation, they have demonstrated their unwavering intent to transform the world even though they have been persecuted by the Taiwan government through both legal and tax measures. They have continued to engage in their global peace efforts and inspire others to do what is right. With the objective in mind, they have self-funded their trips to over 100 countries to foster the love of the world, peace, and the movement of An Era of Conscience.

Finally, it has now been recognized in El Salvador and in the Catholic Church that Romero was not a “divisive” figure, if not in the mind of his assassins and of those who later tried to use him for a cheap political propaganda. He has been proclaimed a saint for the universal Catholic Church, and is widely recognized as such by members of other religions as well. An overwhelming majority of Salvadorans regard him as a national hero. This should be of comfort to the dizi, and confirm them in their persuasion that their protests do not damage, but rather protect, Taiwan. When victims speak up about their traumatic experiences and draw the public’s empathy and attention, it helps the government to face the problems and solve them. Protesting for the truth and human rights is never anti-patriotic, and is in fact the highest form of love for one’s country. It is those who violated the law and breached human rights in the Tai Ji Men case who were anti-patriotic and against Taiwan, as they compromised its image as an island of democracy in a sea that bathes too many totalitarian regimes.

No comments:

Post a Comment