Sister Wendy Beckett: the early years

The art critic, who died last month, made her debut in these pages. The rest is history

In 1986, the television cook Delia Smith gave the Catholic Herald a handful of close-typed manuscripts written by a friend, Sister Wendy Beckett. The nun had originally composed them simply for herself, but then editor Terence Sheehy recognised their quality and, with her consent, began to publish them. Sister Wendy, who died on December 26, aged 88, went on to become one of Britain’s best-loved art critics. Here we reprint some of her earliest columns.

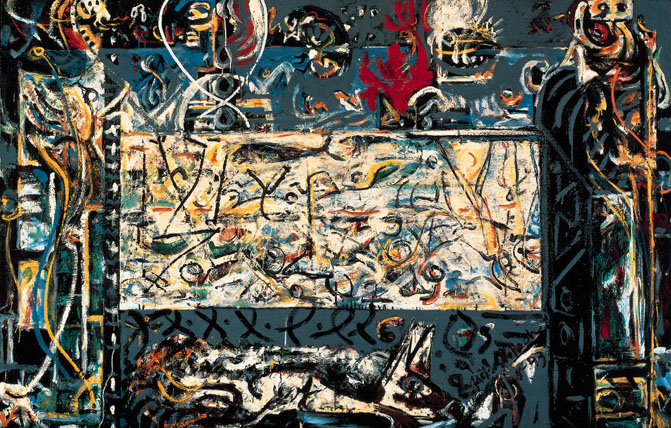

Guardians of the Secret (1943)

By Jackson Pollock

Published December 5, 1986

The New York School, of which Jackson Pollock is probably the greatest exponent, could be seen as almost forced into greatness by existential angst. As the war and its inhuman concomitants reduced man more and more to threatened animality, so did those painters search with increasing power into the myths of the past.

Man was more than beast, and in a time of loss of faith he could seek to find expression of his spiritual potential in the beliefs of earlier ages. Pollock painted specific myths, like Romulus and Remus, and generalised, essential myth, like Guardians of the Secret.

A forerunner of his all-over “drip paintings”, this wonderful canvas is aswirl with mysterious forms. There is a central block: a chest beneath which lives a wakeful Cerberus, scored with hieroglyphics but calmly on guard. On either side of the chest-enclosure stand sentinel figures, both there and not-there, spiritual presences that are only semi-materialised and of whom we can affirm little except their reality. And above the central “secret” we have a border of small wild figures and surrealist fish, enclosing it away from the curious.

What is the “secret”? For us, there is only one secret, that “mystery hidden from all ages and revealed in Christ Jesus”, but even to say this is to be too concrete. There is a bright exuberance about Pollock’s “secret” that warns us it is not to be captured in words, even scriptural. But it is somehow a deep and central joy, and it must be “guarded”.

Perhaps we could be more specific about the guardian than about the secret itself. May not the watchdog be the animal part of us, the body, that hungers and thirsts and makes demands? Its true function, here symbolised, is to be a guardian, to subordinate its natural greeds to a higher necessity, that of keeping watch over the deepest reality within us.

The two half-seen sentinels, then, may be our emotional and intellectual aspects, parts of us that can hunger and demand as ferociously as can our body, but less crudely. These longings too are called to be guardians. Nothing in us is to be suppressed, all is part of a whole, and a necessary part. Mind and heart are servants, like the body, that Jesus summons to a sacred responsibility. This may sound solemn, yet the overall picture, as Pollock shows it, is one of radiance. Accepting the vocation to be guardian of a holy secret is to enter into life’s fullness.

Mother as a Mountain (1985)

By Anish Kapoor

Published March 13, 1987

Anish Kapoor is half Hindu, half Jewish, both traditions which have a great reverence for the mother figure. His sculptures are essentially sacred objects, to be contemplated less for what they are than for the idea behind them.

Yet the numinous can only work on us through the visible, and what is primarily visible, and almost tangible here, are the materials of his work. He has used wood, gesso and pigment, a silent invocation of the powdery pigments used in Hindu festivals. Mother as a Mountain is densely coated with red powder, and it spills out in a tide around the base, keeping the viewer at a distance and marking the place out as holy ground. The graffiti on the surrounding walls express the dim strivings and approximations through which he arrived at the awesome stillness of the final figure.

Julian of Norwich tells us that God is our mother and surely He is the primal mother-as-a-mountain. That gracious regal solemnity that is infinitely protective and infinitely tender, whose beauty is wholly for us, the children. We can never comprehend the holy mountain, but we know that access is not conditional on completeness or indeed anything but need and desire.

The mountain is “open”; we came from it and will return to it. “Your holy mountain rises in beauty, the joy of all the earth,” sings the psalmist. We are too often daunted by the height, the unscaleable degree of the folds. We forget that the Mountain is Mother, more desirous to receive and protect us than can be imagined.

If the sacredness of its being keeps us at a distance, it does not so keep the Holy Son, Jesus. In Him is our access, our safety. Jesus who called Yahweh “Abba” is He who leads us into the heart of the Mother Mountain.

The Flower Carrier (1935)

By Diego Rivera

Published April 10, 1987

Mexico has a rich heritage of folk art, and it had an unexpected flowering in the 1930s in the Mexican muralists of which Diego Rivera is the best known.

Fundamentally a peasant art, it hymned both the nobility and the oppression of the poor in massive and simple forms whose message is unmistakable. A more sophisticated age may decry their oversimplification, but the deepest things are, in fact, simple, and “the mere babes” can see what is hidden from the “wise and learned”.

The picture is all strong diagonals and swelling rotundities. Even the flowers are only seen as round flower-heads. The man has become a beast of burden, carrying his load like the ass, while the woman solicitously supports him. There is a clear visual reference to the position of Jesus fallen beneath the Cross as he struggles on to Calvary.

Yet the pose of the burdened peasant is intense and active. Any minute now, we know he will spring to his feet and bear off his flowers to the market. If he is clad in humdrum white and yellow (sand and sun), his woman is ripe with full-glowing shades of fertility. She is like a flowering plant herself. Perhaps the picture speaks to us of love and its responsibility. We must bow down, bend down, submit and let the weight bear down upon us. The humble and obedient heart is not concerned for itself. The burden is for others – for them the flowers and the joy they bring. We are content, if we love Jesus, to take up the yoke and live simply and humbly in its shade. Others will see us in this picture – a gleaming richness of opulent colour, a rounded beauty, a perfectly balanced pattern.

If our part is to help Jesus achieve this and never to experience it ourselves, then blessed the part that He has given us. In heaven, which this overflowing basket symbolises, the flower-carrier will become flower, flower of the field, as Jesus is called in the Canticles. He is flower to us and He will make us flower for Him.

No comments:

Post a Comment