When you think of the Beats, you think of free sex and flaming sunsets, of bulbous '49 Hudsons easing towards the horizon on dusty highways that seem to go on for ever. You don't think about roundabouts, recycling centres and Rover estates. But that's what you get in Bracknell and it's in Bracknell, near Windsor, that one of the last surviving members of the Beat generation lives.

Carolyn Cassady opens the door to her pretty green cottage with a lipsticked grin and a shy handshake. She's 87, but looks a decade younger, dressed neatly in a lavender fleece with matching moccasins. The second wife of Beat muse Neal Cassady – the man immortalised as Dean Moriarty in Jack Kerouac's 1957 classic On the Road – Carolyn moved to London in 1983, and relocated here 10 years later. "I was brought up English," she says. "My parents were anglophiles and we had a whole lot of English customs at home. I made the break and I much prefer it."

Her knick-knack-filled Berkshire home has now become a regular, if unlikely, stop on the Beat trail. Walter Salles, the Brazilian director behind the new movie version of On the Road, is her most recent high-profile visitor. "He came four, five times," says Carolyn, with a twang that betrays her Tennessee childhood. "We're good friends."

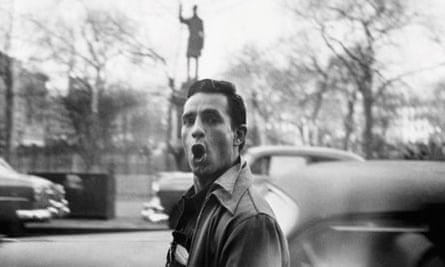

Salles isn't the only one digging around in Beat culture. The 1950s movement, with its freeform writing, bebop sounds and bohemian shenanigans, is enjoying quite a revival. Salles's film, out later this year, will follow next month's Howl, an account of the 1957 obscenity trial surrounding Allen Ginsberg's poem of the same name; and Angelheaded Hipsters, an exhibition of Ginsberg's 1950s photographs, is about to open at the National Theatre, documenting the Beats' now legendary roadtrips and rooftops.

"Why this sudden interest in Ginsberg?" says Carolyn, sitting at her polished dining room table. "I met him when he was 20. He had never got over feeling he was worthless. He'd go out and try to find a job, and he'd come back and he'd say, 'I'm never gonna amount to anything. I just can't do anything. Even my finger's the wrong size.' He'd tried some assembly line or something." With a sigh, she says she remembers him as a "poor dear".

'Burroughs called me a WASP bitch'

For the last 10 years of his life, Ginsberg stopped speaking to Carolyn. Does she know why? "Bill Burroughs decided I was a WASP bitch." Nevertheless, Carolyn has become something of a gatekeeper to Beat history, writing a warts-and-all memoir, Off the Road, in 1990, answering fans' emails, and consulting for the likes of Salles. Her life has been, and continues to be, shaped by these long-dead male icons. Ironically, she is mystified by the fascination. "Kids in school are still eating it up. I don't understand it. I don't see any value in that at all, culturally." Not even in reading Kerouac? "If I hadn't known him, I never would have read any of his books."

Born in Nashville in 1923, Carolyn first met Neal – "the holy conman with the shining mind", as Kerouac had it – in 1947, when she was a blonde beauty studying art and drama in Denver. One afternoon, Bill Tomson, an unrequited suitor, called by with Neal. "I was mad at Bill because I wasn't prepared," she says. "I was in this dowdy old dress. He [Neal] sat there rocking in the chair and asked if he could play some of my music. His blue eyes were just like lasers – he had this aura."

Neal's reputation preceded him: in Off the Road, Carolyn writes of the "extraordinary exploits" Tomson told her about. Brought up by an alcoholic father in Denver, Neal stole cars in his teens and served time in 1944, aged 18. It was three years later, when Neal and his 16-year-old first wife LuAnne Henderson met Kerouac and Ginsberg in New York, that the mythical figure began to take shape. Not only did Kerouac put him in On the Road, Ginsberg also namechecked him in Howl, as his work's "secret hero".

Idolised for his fast driving, hyperactive energy and voracious reading habits, Neal was the perfect Beat character, and his autobiographical writings were published posthumously as The First Third. "To sit still and write was agony for him," recalls Carolyn. "He said he'd think of a word and he'd think of 10 others." Instead, Neal dashed off free-flowing letters that influenced Kerouac's style.

The two married in 1948 and spent the next 20 years observing the Beats. Sort of. "I'm one of the last survivors and, of course, I wasn't a part of it really," says Carolyn. Certainly, there are no images of her in Angelheaded Hipsters, which takes its title from the opening lines of Howl: ". . . angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night."

Although she had a Neal-sanctioned affair with Kerouac, Carolyn was very much the stay-at-home housewife, a middle-class "status symbol" for her husband, who lived a double live of domesticity with her and decadence on the road, often accompanied by LuAnne (who he was still sleeping with). "When he was home and supporting a family, he had what he aimed for – respectability. But then it got a bit boring for his adventurous spirit."

His infidelities include the LuAnne affair, and getting model Diana Hansen pregnant when Carolyn was also expecting; he married Hansen in 1950, bigamously. Carolyn also found him and Ginsberg in bed together – twice. To make it worse, some of this was then rehashed in fiction. Big Sur, Kerouac's 1962 novel, concerns the love triangle between Neal, Carolyn and the author, while On the Road is a thinly veiled account of a trip Kerouac took with Neal and LuAnne when Carolyn was pregnant with their first child. She didn't read the book until long after its publication. "It was too traumatic," she says. "I don't want to read about all the fun they had. I was still so conventional, and this was like desertion."

She is adamant, however, that the more ordinary side of Beat life should be told – even if it contradicts the drug-fuelled, bebop-soundtracked folklore. "We had this traditional, conventional home, and I think that's why Jack and Allen loved coming there. They were much more conventional than people think," she says. "They never swore in front of mixed company, ever, and they would pull your chair and open car doors. They were all perfect gentlemen."

Cassady believes the Beats were misunderstood. While Ginsberg enjoyed the adoration that came with fame, Kerouac drifted into alcoholism. "The kids thought he was promoting leaving home and dropping out of school and taking drugs. And of course, he wasn't." She sighs. "He was so devastated by that interpretation that he vowed to kill himself and he did." Kerouac died in 1969 after a haemorrhage caused by a lifetime of heavy drinking.

'He was treated like a trained bear'

Carolyn maintains, on her website, that the "real Neal" was a family man who looked after his three children and always had a job – often on the railways. But, she says, "the kids all seem to prefer the Ken Kesey life". After Carolyn divorced him in 1963, Neal became the party-man on the LSD-fuelled Merry Pranksters bus, led by Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. "They treated him like a trained bear. Neal said he took any drug, any pill, anyone handed him. He didn't care. He was doing his damnedest to get killed." She feels guilty about his self-destruction. "I didn't realise the two pillars of his support were the railroad job and being head of a family. He realised he would never become respectable, as he wanted, and he wanted to die."

In February 1968, he succeeded. While the details of his death are almost as mythologised as his life, what is known is that he was found by some railroad tracks in Mexico, after mixing beer with barbiturates, possibly at a wedding party. Carolyn has been single ever since. "I have never met a man remotely possible," she says. "There wouldn't be anybody to match Neal."

No comments:

Post a Comment