The Story of Father Francis, Part One

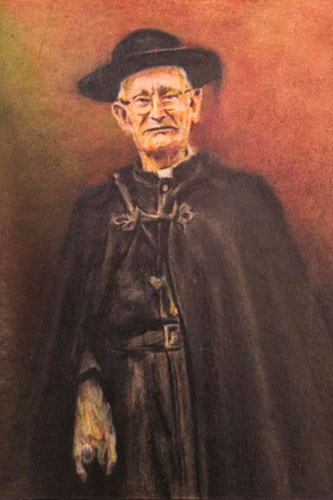

The man Woodstock knew as “Father Francis” is not remembered to have ever publicly discussed his decision to become a priest. The clergyman, who presided over the Church on the Mount atop Meads Mountain from the 1930s until 1979, who enchanted Woodstockers, married many and guided the spiritual needs of an unruly community, would refer as his great turning point to an act involving him, as an archbishop, assisting Clarence Darrow in defending a high school instructor arrested for teaching Evolution in what came to be known as “The Scopes Monkey Trail.” So while 1925 newsreels of Darrow and Father Francis may somewhere exist, Tobey Carey’s remarkable 1974-75 documentary Father Francis doubtless remains the most thorough audio/visual record of the clergyman, and it can be found at the Woodstock Library. Hence, where historical disagreement in public record exists, I defer to this unsworn testimony of Father Francis. The half hour film captures FF nearing his end, and is therefore missing a few beats in the remarkable delivery which endeared him to so many. However, one of the most striking features of these interviews remains the following: Originating as he did from upper-crust England — and obviously the product of a rich storytelling tradition — the monologues of Father Francis rarely differentiate between “the speakers” populating his anecdotes. Instead, like his contemporaries Joyce, Faulkner, and later, Cormac McCarthy, the teller of the tale leaves that work to us.

The man Woodstock knew as “Father Francis” is not remembered to have ever publicly discussed his decision to become a priest. The clergyman, who presided over the Church on the Mount atop Meads Mountain from the 1930s until 1979, who enchanted Woodstockers, married many and guided the spiritual needs of an unruly community, would refer as his great turning point to an act involving him, as an archbishop, assisting Clarence Darrow in defending a high school instructor arrested for teaching Evolution in what came to be known as “The Scopes Monkey Trail.” So while 1925 newsreels of Darrow and Father Francis may somewhere exist, Tobey Carey’s remarkable 1974-75 documentary Father Francis doubtless remains the most thorough audio/visual record of the clergyman, and it can be found at the Woodstock Library. Hence, where historical disagreement in public record exists, I defer to this unsworn testimony of Father Francis. The half hour film captures FF nearing his end, and is therefore missing a few beats in the remarkable delivery which endeared him to so many. However, one of the most striking features of these interviews remains the following: Originating as he did from upper-crust England — and obviously the product of a rich storytelling tradition — the monologues of Father Francis rarely differentiate between “the speakers” populating his anecdotes. Instead, like his contemporaries Joyce, Faulkner, and later, Cormac McCarthy, the teller of the tale leaves that work to us.

He began English-born in 1882 as William Henry Francis Brothers, the eldest son of a Nottingham lace manufacturer (“Dad ran with Lord Buxton and that crowd”) who emigrated with his large family to America just before the turn of the last century before settling in Illinois. William was 12. Ordained at a very early, if unidentified age “Father Francis” soon joined the Benedictine Monastery in Waukegan where he worked primarily among a the local poor, largely illiterate immigrant population. In 1907 the monastery and its missions were accepted into The Old Catholic Church based in England, and Father Francis became abbot of the community in 1913 at the age of 25. Consecrated as bishop on October 3 of 1916 (by Bishop and Prince de Landes and Burghes de la Rache of the house of Lorraine-Brabant) FF immediately became embroiled in inter-denominational battle. For the very next day a certain Carmel Henry Carfora was also consecrated as bishop and soon assumed leadership of Northern American Old Roman Catholic Church, whereas Bishop Francis was a defacto patriarch of The Old Catholic in America.

In 1917, clergy of these “Old Catholic” branches met in Chicago and pronounced each bishop the archbishop of the two rivalrous-if-related sects, (neither of which acknowledged the Pope as a supreme or infallible spiritual leader.) The upshot being, as Alf Evers put it, that each man soon “accus[ed] the other of being a self-made archbishop.”

In Carey’s film, Father Francis, then 93, recalls at first, while “very conscious of being a bishop” he remained “an unashamed Pacifist when there were only five known Pacifists in public life.” As such, around 1916, he sought to free an imprisoned young draft dodger while knowing he’d need “the attorney for the damned” Clarence Darrow, to get the job done. “Of course I’d heard of Darrow. Who hadn’t?”

Without making an appointment FF found his man on the 9th floor of the Cunard building in Chicago, where the chain-smoking attorney quick waved off his staff with: “He’s a bishop? I’ve never talked with a bishop before.” Father Francis’ love of paradox leaps from the recollection with: “Darrow was so ugly he was good looking.”

“You’re awfully young to be a bishop.”

“Well, I’ll grow up.”

“Do you eat?’

“Well, I don’t drink.”

Moments later the notorious firebrand took “a young cleric’s arm” and walked him through an amazed Henrici’s restaurant. At the end of the meal, during which Father Francis had pleaded the draft dodger’s cause, Darrow said, “I won’t let you down” before asking if FF came into town often.

“If necessary I do.”

“Well, whenever you come into to town, come have lunch with me. I kind of like you.”

“Well, I kind of like you, too — especially if you take the case.”

They became friends. They went night clubs together. They even got into an automobile accident together.

Then FF became “Archbishop Francis” and moved to his church headquarters of Stuyvesant Square in Manhattan. In the process a greatly misunderstood event occurred (which recently prompted an eloquent if unevenly researched letter to the editor of this paper, proposing proof of FF’s “dark side” with descriptions of matrimonial abuse.) The truth was this. At an unknown date the parents of mentally disturbed young woman were killed in an accident. FF was charged with the care of their daughter, Edna, who became his ward. To fulfill this duty even after becoming archbishop, FF tried to take Grace with him to New York City, but was blocked by Illinois law from transporting a minor across state lines. Darrow often said that Father Francis would’ve made “one hell of a lawyer,” a claim which FF initially proved by flouting laws of both church and state in promptly legally marrying Grace. Needless to say, the marriage was never consummated, though — yes, several decades later FF found it necessary to place Grace in a mental institution where, yes — he likely responded to her complaints in explaining “there is no justice in the world…[only in heaven.]”

It was 1924. Clarence Darrow had tracked down the phone number of FF’s new headquarters to inform the archbishop that a young high school teacher had been arrested for teaching evolution in Dayton, Tennessee.

“Well that’s ridiculous. They teach it in every high school.”

“Oh no they don’t. Now I want you to go down there with me if you can. I need your help to steer me through the bible. You must know it better than I do.”

Father Francis asked for a day or two to think it over, then agreed. He next asked Darrow to transport him to Chicago so they could prepare and FF could see his father.

“You can’t get mixed up in this business,” his father told him, “besides it’s impossible.

“But Dad…I’ve decided I will get mixed up in it.”

“Well, when the church throws you out what will you do then? What will you put on your altar then?”

“I’ll put you on the altar, Dad.”

Father Francis capped the story: “He looked like he’d punch me.”

Although the archbishop was careful never to state this fact, his Beautitude, Metropolitan John (the present Archbishop of FF’s order) assures us that it was indeed Father Francis who supplied Darrow the remarkable strategy which eventually set John Scopes free. The figurehead advisor to the prosecuting attorney in the case, of course, had been orator William Jennings Bryan (who’d repeatedly run and was once only narrowly defeated in assuming the office of President of the United States.) As memorably documented in the play and film “Inherent The Wind” Darrow and Bryan were old — if rivalrous — friends. Even so, the battle playing out in Dayton, Tennessee soon took on shades of a modern day David and Goliath with Darrow, naturally, defending the underdog, and Bryan using the implicit publicity to embolden yet another attempt to lead the nation back to God as President.

Then on July 20, 1925, after excessive heat had moved the proceedings outdoors, Clarence Darrow called his evermore confident adversary, William J. Bryan, to take the witness stand as an authority on the Bible. Although star reporters from all over the country had presumed upon a stunning defeat for Scopes and so had already left town, Clarence Darrow now mounted what is generally considered the single most brilliant gambit in the history of the American courtroom. It went something like this:

“Do you believe in the seven days of Creation?”

Under oath Bryan assured the court he did.

“And by the dictates of this belief, when was the sun made?”

“On the third day.”

“Fine, and with the sun made on the third day, if you would sir, might you please explain how the sun might rise or set on the first and second days? Indeed, could you explain how these periods might be called ‘days’ at all without the sun providing such ‘days’ their light?”

Bryan was hogtied. Utter chaos resulted in the courtroom and in the following weeks, months, and years in churches, schools, and governments all over the world. The following day the judge refused to withdraw the testimony and, after a seven minute deliberation (one minute — no doubt — for each day of creation…) Scopes was judged guilty of teaching Evolution in violation of the recently passed Butler Law, and fined one hundred dollars. Darrow offered to pay the fine which was soon withdrawn on a technicality. Five days from the ruling William Jennings Bryan was found dead in his bed. Father Francis’ comment being: “And so the world’s greatest prohibitionist had eaten himself to death.”

After inspiring this blistering defeat to Old Time Religion Father Francis returned to New York where he was literally spat upon by the righteous, and found “old friends wouldn’t even look at me.” Still shocked by the events well past age 90, FF — since famously known as “Woodstock’s Hippie Priest” — seemed mortified all over again while admitting, “It completely changed the whole course of my life…[Then] instead of spending my time with bible-loving people, I found myself with those who ultimately formed the civil liberties union.” But once branded a renegade there was no going back, so the Archbishop embraced the controversy surrounding him, and used it towards his own ends.

“…I’ve also spoken before the Aetheists Society of America which is also known as The Libertarian Society [and] The Society of Anarchists…And that was the time I told them: ‘Now give me three minutes and if I don’t make my point throw me off the fire escape at the back. Because I want to tell you about the greatest Anarchist I ever knew: Emma Goldman.’ [Aside:] After that I was with Emma Goldman on the platform of the Town House in New York. ‘I knew Alexander Berkman [who attempted and failed to assassinate Henry Clay Frick], Ben Reitman [who drove “Free Love Emma” into murderously jealous rages]…names familiar to you all. But the greatest Anarchist of all — you didn’t know — but I did. Now let me tell you about him — and he was Jewish, too, as most of you are…Jesus of Nazareth.’”

Father Francis also adapted, produced, and acted in plays to packed houses at St. Marks and the Bowery. To cast the first of these, a nativity play, he appealed to Eva Le Gallienne, “the great genius of the Civic Theater, who knew exactly what I wanted — but she didn’t…Finally she brought me a willowy 17-year-old Martha Graham [Graham was 25], who had never danced in public before [probable.] I remember I said, ‘But she won’t do at all. I want a big fat Yiddisha Mama.’ And Le Gallienne thought that very sacrilegious. But well, isn’t it true? The Blessed Virgin Mary? She probably wasn’t in the least as we think she was — certainly not afflicted with chronic anemia. [Laughter.] Yes, that’s how I knew Martha Graham. She performed in mime. We had readers between us. I said, ‘Well, she’s read the script. Let Miss Graham see what she can make of it.’ And in the end she was so beautiful, so wonderful…I won’t say who wept but most did. So I looked at her and said, ‘You have a job.’ And apparently we were good because the Moscow Arts Theater had gotten into the country somehow, and they came to see us. And they approached [co-producer] Dr. Guthrie and expressed an interest in hiring me. [To which] Dr. Guthrie said, ‘You can’t hire him, he’s a bishop!’

‘— He’s not a bishop, he’s an actor!’

“So they came to see me and I said: ‘No I’m not—I’m both!’”

(Courtesy of Lawrence Fine)

Like all charismatic spiritual teachers Father Francis was and obviously remained a showman with the sin of pride shining through his piety like a mirror’s silver through the glass. This gifted actor of an archbishop, for instance, specialized in dragging high society matrons to charity hospitals. Here, while softly intoning prayers over the semi-conscious, he inspired such wealthy friends to write checks for newer and better such institutions — checks often accompanied by a surprising number of zeros. The opening of such purses evidently justified (and paid for) Father Francis’ domicile in what was likely the single most gorgeous residence in all New York. It had been designed and built for his own use by the man commonly considered America’s greatest architect, Stanford White, who was obliged to vacate the premises the night he was shot dead in the tower of Madison Square Garden (which White also designed) by Harry Thaw, for making love to Thaw’s intended, Evelyn Nesbitt, on a velvet swing which hung from the high arch of that tower.

And so eventually, for exactly ten years between 1926 and ‘36, while attended by four other priests, Father Francis (…the closeted Grace no doubt playing Mrs. Rochester in the attic above) underwent his most decadent phase. It, nevertheless, abruptly ended with the confluence of three increasingly remarkable events.

First, Father Francis received a pompous visit from an officer of the savings bank on 72nd Street informing him that his ten year lease had expired but since — in light of the numerous repairs and improvements he’d made on the place — the archbishop could plainly not afford to not sign another ten year lease, though the rent was now doubled. The document along with a priceless fountain pen were then placed before his Eminence. “Well, [said FF] I can live in the gutter but I won’t be blackmailed by a banker.” So, as he invariably would in such circumstances, Father Francis exasperated this most self-important chiseler in requesting “two weeks to think about it.”

Only a few days later a subordinate, visibly flustered by whatever was making quite a ruckus below, climbed the stairs and entered FF’s cloistered apartments.,

“There’s a man to see you. He says he’s your father.”

“Well, I had a father — I’m not fungus growth.”

“But it can’t be your father — he has blue eyes.”

“My father has blue eyes!”

So Father Francis descended the grand velvet stair to find his dear old father unwilling to pay a cabbie.

“Dad! Why didn’t you write to say you coming?”

At this a torrent of vitriol poured from the mouth of the elderly gentleman, ending with: “Why Jesus Christ couldn’t get to see you!”

“But Dad…He wouldn’t come to see me, He knows me too well. Now come upstairs to my private quarters.”

“Oh and you’ve a private quarters in addition to a palace for a home!”

“Well, I am an archbishop…”

“And you’re well aware of it, aren’t you?.. With people starving to death on your door — I’m ashamed of you!”

[FF recalling the event:] “And his blue eyes were flashing fire…but of course, he was right!”

Finally within the same week Father Francis remembers receiving a letter from “Mrs. Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead, saying she had problems and we had mutual friends and would I come to spend the day with her at a place called Woodstock. Probably I’d heard about it. Of course I’d heard about it. Everybody had heard about Woodstock in those days.”

Father Francis arrived Woodstock in 1936, here met by Jane Whitehead “this tiny little woman in seven veils,” who soon revealed that her son Peter, then in his early 30s, was a problem. “Peter was not a problem,” Father Francis explicitly states in interview, “…she was the problem. Peter was never a problem to anybody.” This euphemism politely communicates the fact that Peter Whitehead was a jovial if chronic drinker for whom procuring more alcohol — and just about anything else he desired (except a suitable wife) — never presented a problem to anybody. So Peter proceeded, in an affable way, to remain what he was: an ever-welcoming and most generous drunk. Nevertheless Lady Jane, his mother, was convinced that a teetotling, non-smoking, eloquently amusing, yet distinctly pious Archbishop could and would somehow produce a remarkable change in her sole heir. She was so convinced of this, in fact, that she made Father Francis an extraordinary offer, which — in his way — he requested some time to think about.

Peter drove him the back way up the mountain destined to become his domain. “I’d never been up a mountain like this before.” Father Francis knocked on the door of Mead’s Mountain House and the surviving grand daughter of old man Mead answered it to say they hadn’t any rooms at the moment. Father Francis said he was neither a roomer nor a rumor and simply wanted to rest a while and think. She started coffee for him.

“I told Peter [back in the car] he should call for me in two hours, for Mrs. Whitehead had told me that if I’d come to Woodstock part of the year she’d give me the mountain. I said, ‘I don’t want the mountain, I want part of it.’ And Mrs. Whitehead said she’d give me what I wanted if I’d come and look after Peter. So I thought it all out and they picked me up about four o’clock and took me tea at what is still Byrdcliffe, and I decided in the affirmative and that’s how I came to Woodstock. I liked it. I tasted freedom here. I started to build what was a house that turned into church…” Here the interview is cut short and so, in the same spot, is this history. But next week Father Francis will be alive again for a few thousand words anyway and — despite a dark and fearful world howling all about us — some might look forward to that.

The Story of Father Francis, Part two

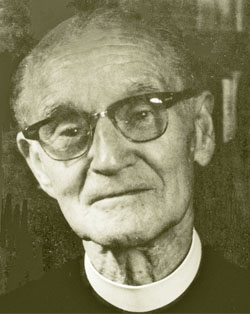

(Photo by Dion Ogust)

The conclusion of last week’s history of Father Francis found him at a dramatic turning point. In 1936 his rent at Stanford White’s opulent Manhattan town house was poised to double. His father’s scathing criticism of such luxury still ringing in his ears, he traveled north to hear Jane Whitehead’s proposal of “come to Woodstock and help with [her son] Peter” — a proposition which must have seemed like an intercession of Providence towards rescuing this most decadent archbishop from himself.

We know Father Francis embraced this rescue and as a result radically changed the spiritual life of Woodstock more than any Christian clergyman before or since. But first he would be deeply changed by this “Colony of the Arts,” himself. Eventually those old Catholic teachings he espoused were joined with “the back to Nature” credo Ralph Whitehead’s Byrdcliffe had hoped to seed here. Ironically, it was due to privilege and its prejudices that Byrdcliffe failed. In other words, Whitehead foundered on the very reef of class and wealth Father Francis sought to at least partially escape; while, admittedly, accepting the patronage of Whitehead’s widow, Lady Jane.

However FF’s choice of exactly where and how he’d set up in Woodstock reflects an instinct to insulate himself from Mrs. Whitehead’s influence. For had this Lady’s generosity indeed been of the magnitude FF described [in Part I] she’d gladly have transformed an existing Byrdcliffe building or simply built Father Francis a church near herself and Peter in their doddering empire. Instead something happened — something which assured FF it was she, not Peter who was “the problem.” In the end Father Francis converted a barn (off what is today Route 212 on the way east out of town) into a church/residence he called “St. Dunstan’s.” [Deeds for which bear neither the name “Whitehead” nor “Brothers”— so FF likely rented.]

When St. Dunstan’s burned “despite the heroic efforts of the Woodstock Fire Department” in early January of 1945, the Kingston Freeman snidely reported that the Archbishop’s wife lived in a converted chicken coop next door.

There were treasures lost in the fire, but little else is remembered of St. Dunstan’s except that Father Francis there performed the marriage of Harvey Fite (builder of Opus 40) to Barbara Richards. Harvey first came to Woodstock as an actor presumably to appear at the Maverick Theater. So it may have been at his wedding that FF first met Ralph Whitehead’s self-exiled protege, Hervey White, whose bisexuality was an open secret at his “retort” to Byrdcliffe — that by-then legendary and most radical artist’s enclave Hervey called simply “The Maverick,” four miles away. White’s cryptic (and unpublished) autobiography states that a strong friendship sprang up between these two Edwardian age revolutionaries, and that Harvey become a “confessor” to the archbishop, which we may surmise to have been a reciprocal relationship. For each man was, among intimates, known to be gay (yes, such usage then existed — if obscurely), despite FF’s

“cover” of an insane ward for a wife, and Hervey’s disastrous marriage, the dissolution of which broke his heart in ways too numerous to recount here. (Concerning FF and this claim, I possess testimony of a grown man, fully unnecessary to this account.)

Soon following the fire, FF accepted Mrs. Whitehead’s gift of a modest Episcopal chapel built in 1891, first called “The Chapel of Ease,” which Lady Jane bought from Mrs. Hutty (who’d made FF coffee in her Mead Mountain House that first afternoon he decided upon Woodstock). Hervey White was a year dead, the world war had been won, and our sprawling colony was soon enriched with a second wave of painters, few of whom wanted anything to do with religion.

Yet the tradition sprang up among revelers on Christmas eve of shoving off from the last of many Woodstock parties and somehow negotiating those sweeping turns on Mead’s Mountain to — at its top — attend Midnight Mass at the tiny chapel. Here, at the end of the carefully shoveled path, celebrants packed into that magical shoe-box redolent with Frankincense and lit only by candles. Some of them sang as others snored, while still others listened and gazed amazed at Christ’s mass on Christmas. And then? The aging fox had them just as he’d wished: inebriated, nostalgic, and at his mercy.

Today of Fleischmans and 91, Bud Sife was FF’s driver between 1949 and 51. (He would also eventually build and operate Woodstock’s first late night rock club, The Sled Hill Cafe.) Buddy remembers taking FF on many trips to varying diocese churches in Philadelphia and New York. “He was always preaching and teaching to his clergy. He was a teacher first and foremost. And — although he knew I was an atheist — I admired him for the most part — and his church.” Sife explains that FF spoke about “Christ the man” and the principles laid down by this human being known as Jesus of Nazareth. “I’d say Father Francis was a humanist as much as he was as a Christian with little or no distinction between the two. They were simultaneous in him.”

There were and are many shouters among America’s clergy, but the tiny theater comprising The Church on The Mount allowed Father Francis to instead assume the mantle of The Great Whisperer. Now to explore the remarkable efficacy of those quietly uttered words we jump to the early 1960’s, when FF initiated a wave of conversions which — to this day — boggle the mind.

Father Francis himself recalls his earliest involvement with flower children of 60’s in an article he wrote for “The Churchman” [fast reprinted in the May-June ‘73 issue of The Woodstock Oracle.] Demonstrating no diminishment in his flair for controversy, FF entitled the piece “Hippies — Hope for the future.”

It began: “An article in a recent NY Times referred to a phenomena that has arisen universally as ‘The Woodstock Nation.’” FF next supplied his credentials to comment on the phenomena before explaining:

“My first experience with a hippie was several years ago [1964] when I invited a long-haired youth to spend a January night in my ‘Prophet’s Chamber,’ rather than risk his life in a blanket on the church grounds. Over a cup of coffee this youth quoted Kahlil Gibran and other such writers. [The] next morning he remarked on my building project (I was only 82 years old then), ‘Father, you need help.’ That was a gross understatement! Well, Frank stayed with me, worked with me and later brought some of his hippie friends. This beginning started my life in another world — a world that I had long sought in holy Mother Church. Sharing with these youths my home and life I learned first hand of their hopes and aspirations in this crazy, confused world — the world rubber-stamped with ‘In God We Trust,’ a sad slogan to try to cover hypocrisies.”

In essence, Father Francis (who’d recently been dubbed “The Hippie Priest” by the NY Daily News), became a bridge between that fantastical realm of the 1960’s and his own brand of Christianity, which in its sanitized form proved a religion most convenient to the dog-eat-dog world surrounding and soon re-conquering the brief experiment known as “Woodstock Nation.” However, FF clearly sided against the dogs and wolves of the world, as well the machinery of Rome (and its grand equivalents in Reformation churches) upon becoming shepherd to the many lost lambs hurried away by — among other horrors — corporate religion’s rumblings.

In what now emerges as an increasingly complex chess match, it was also around this time that FF, in his official capacity, made a trip to California. Here he tangled with Richard Nixon (whose presidential bid had just been stolen by the Kennedys and was soon narrowly defeated in his attempt to secure Governorship of California in ’62.) Predictably enough Father Francis is said to have given Tricky Dick quite the trouncing in a private kitchen, a battle which evidently inspired him to go even further in speaking out against “this crazy confused world…rubber stamped with In God We Trust.”

But before proceeding we need to recognize the hole cards of history at play here, namely: a) Richard Nixon’s beginnings with Joe McCarthy (which puts Dick in tight with J. Edgar Hoover); b) Nixon’s strong tendency to hold a grudge and seek revenge; c) FF’s “coincidental” decision in 1962 to align his church with The Russian Orthodox church — itself at the whim of a flimsy olive branch held out by Khrushchev.

While, d) FF also safeguarded this radical removal from perceived stateside enemies, by his creating a loophole — unique to the nation’s history — here in the US of A. Through it the archbishop also protected his entire church from a change of policy in Moscow. Such Richelieu-like maneuverings soon found FF’s old friend Peter Whitehead leaving the 400 some acres associated with The Church on The Mount to the town of Woodstock [more thoroughly explicated in a piece concerning the The Church some weeks ago]. This in turn reflects a portion of the grandiose offer FF alluded to that fateful day in ‘36 when he accepted Jane Whitehead’s proposal that he move to Woodstock in exchange for “part of the mountain.” Do note however, the gift to Woodstock from Peter W also proves that FF was never formally deeded such lands — but that Peter Whitehead made good on his now deceased mother’s promise, nonetheless. What we don’t and probably will never know is to what extent FF undertook the spiritual guidance promised to Lady Jane of her son Peter (which Mike Esposito suggests was nominal.) Now back to this remarkable period in the 1960’s when FF spearheaded what became known as “Hippie Christianity.”

Father Francis

While His Beautitude, Metropolitan John Lobue (the present head of FF’s order) insists that Father Francis sought first and foremost to formally convert attendees of the Church on The Mount, a great deal of evidence argues otherwise. Many of FF’s flock, for instance, had or would kneel at the feet of a vast assortment of teachers, seers, gurus, and would-be messiahs on their way through town — proselytizers who certainly sought to “sign ‘em up” — whereas FF required no such membership from his growing family of, shall we say, problem children. Any one of whom was free to try out Sufism or Taoism or go to this or that new meditation center. Yet if or when someone freaked out, faltered, or fell, The Church on the Mount was always there to welcome them home. And so, by specifically not insisting upon strict conversion — by the droves — that is precisely what Father Francis accomplished. For instance…

Contrary to popular belief, Michael Esposito was already retired from the seminal psychedelic rock band The Blues Magoos by the time he moved to Woodstock in 1967. In fact, he was reading The Lives of The Saints — so he was ripe for the picking.

Michael recalls an aura surrounding Father Francis. Furthermore Esposito clearly states: “Father Francis didn’t reach out to people, they pretty much came to him. [He’d be] sitting in that little study back there…[that room] from another epoch. You go back 500 years and there would be someone like him sitting in his study, with the same old books and artifacts from the church. He was the conduit for all these ancient things. And they had a power all their own — just being in the same room with them and with him — their messenger…it cast that aura. It was like living inside a really well-written novel.”

Someone wove Michael a medieval robe and he moved into a tiny room on the side of the church; the periodically-unwound Father Daryl (the shotgun bearing Father Jude of part one) lived in similarly cramped quarters. But around all this Christian pseudo-renaissance — what of FF’s reception among the other churchmen in town?

Esposito remembers: “Yes he was — you might say — voluably disparaged by the local clergy. Most of the local churches here, they’d have a smattering of attendees on a Sunday, whereas Father Francis had a real following. [Part of the reason being] Father Francis gave great sermons. It was like being backstage on a late night talk show. He was wit incarnate and knew history, cold. He wouldn’t get into the moral side of right or wrong. But he would make fun of people who thought they were right, and he’d make fun of people who were clearly wrong. And his delivery, that soft but deadly erudition — you didn’t — you couldn’t hear anything like it anywhere else. And so — yes, he was adored for it.”

Michael also distinctly recalls Bob Dylan’s spectral presence. “He’d be in the back room, looking over the ancient tomes, eavesdropping you could say on the liturgy and sermons while rarely showing his face. But Father Francis would go back and speak with him at length — you bet your chasuble he did.”

The Metropolitan Museum eventually undertook to publish FF’s 1965 “Day Book” (copies of which are purchasable on Amazon at $600). It contains numerous mentions of Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, whose many appearances at the chapel may well have inspired Dylan’s interest. (It certainly wouldn’t be the first time Jack provided a model for Bob…) While Dylan’s “Born Again” period didn’t formally begin for another decade, the anomaly of his “Father of Night” (many believe to have been inspired by FF) on Bob’s 1970 release “New Morning,” more than testifies to the life-changing charisma approximated here. Embedded in a lyric supposedly commissioned by Archibald MacLeish (which certainly refers to a grander subject than FF, namely, the architect of the universe) Dylan includes the lines “Father of loneliness and pain, Father of love and Father of rain.”

Although Father Francis must have presided over many funerals, the predominant youth of his flock finds him best remembered for joyous marriages and baptisms. He married most all the artists in town and our hippies [as well my mother, “both times,” while baptizing two of three sisters and myself at five.]

Elsewhere, Tobe Carey’s priceless documentary “Father Francis” captures many of Woodstock’s more memorable reprobates in highly incongruous worship. Yet FF’s most lasting achievement remains his insistence upon looking past divisions in religion to concentrate on a universality at their core. For instance, as Violet Snow noted, on Saturdays FF “opened up the building to a Jewish congregation for their services.” (Although I can’t resist mention that John Lobue speaks with frank admiration of FF’s specialty in converting Jews.)

The most controversial — and some would say harmful — aspect of FF’s spiritual generosity, of course, was the remarkable welcome FF gave to Kalu Rinpoche and his Tibetan retinue when, in the early seventies, they began negotiations to purchase the Meads Mountain House along with its meadows and orchards. This being the exact spot where in 1902 modern Woodstock’s discoverer, Bolton Brown, and then 34 years later, Father Francis, each fell in love with all that surrounded them, the distant Hudson, and the jewel of a village nestled below.

Michael Esposito: “Father Francis was always aware of his duties both as archbishop and local friar. He was off to several of his churches Lord knows where and we’d drop in on Woodstock parties where he’d pay his respects before being off again. So when he suggested a tea with the Tibetans in the meadow over the wall, I figured [this would also be] a short, polite visit…I took his arm and up we went, [there was] bowing with clasped hands at chest and all. Father Francis was invited into a suitably grand chair — he liked that — and tea was prepared. English style for him, of course. But once the translators got to work something remarkable happened. The two masters’ faces lit up with what you’d have to call an astounding — yeah — a recognition of one another…and they started to laugh. Soon the translators couldn’t catch up and the two were convulsed in peals of laughter before either knew exactly what he was laughing at. And evidently they hadn’t stopped laughing for the entire two hours I [went away and] left them to their fun before finally returning for Father Francis who spoke to me of little else for several days.”

But what no museum has yet placed hands upon is the diary Esposito kept through many of those remarkable days, days which ended for him when he came off the mountain; days which ended for us all when, after many a glorious summer, our ancient Patriarch finally breathed his last in 1979 at the age of 97.

At the ornate funeral, however (after which priests of his order performed 24 hours of prayer over Father Francis’ grave) many of the ragtag parish grew impatient with a most alien-sounding liturgy read in what now seemed the grating Brookyn-ese of a one-time cub reporter for the NY Times, His Eminence John Lobue. Indeed, as all inheritors of FF’s worm-eaten throne would quickly learn, their predecessor was one tough act to follow. For soon, after a period of increasing grumbling, actual rebellion broke out. Three of the more colorful Woodstockers scattered among the crowd caught one another’s eye, fell into conspiracy, and stormed the tiny bell tower. Now S—, B—, and E— violently rang that solemn bell, succeeding in drowning out the ceremony until they were restrained, whereupon the trio promptly left in disgust.

Of course, the reasons for their ringing of that bell were initially plain enough. Yet in coming years, after the first had been shot through the heart by a jealous husband; after the second — terminally ill — bravely chose to take his own life; and after the third — without a single complaint — finally died of the drink… Yes, I would distinctly hear Father Francis carefully reminding us all in that frail, quivering, if ever-passionate voice, of Donne’s admonishment: “Do not send to know for whom the bell tolls — my dears…it tolls for thee.”

No comments:

Post a Comment