The new Catechism text on the death penalty will damage the Church

The Catechism, before the latest revision

Yes, the revised wording is unclear. But it certainly seems to imply that previous popes led the faithful into grave error

Pope Francis has changed the Catechism so that it now declares the death penalty to be flatly “inadmissible”. Whether he is teaching that capital punishment is always and intrinsically evil is a matter of controversy, but taken at face value, the wording of the revision at least seems to say that. And while it is important to understand the exact magisterial weight of the new text, we also have to deal with the obvious reading: that, as the BBC put it, “Pope Francis has changed the teachings of the Catholic faith to officially oppose the death penalty in all circumstances.”

Along with many other commentators, I have noted that this apparent rupture with Scripture and tradition damages the credibility of the Church and the papacy. A close reading of the new text only increases one’s concern.

The 1990 CDF document Donum Veritatis acknowledges that it is possible for magisterial documents to exhibit “deficiencies,” and that Catholic theologians have the right, and sometimes even the duty, to express respectful criticism of such deficiencies. There appear to be at least three major deficiencies in the revision to the Catechism:

- The new wording appears logically to imply that Scripture, the Church’s previous catechisms, and previous popes including St John Paul II all led the faithful into grave moral error.

Here the most problematic element of the revision is its assertion that “the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person”. There are a great many passages in scripture that not only allow, but in some cases even command, the infliction of capital punishment. To take just two examples, Exodus 21:12 states that “whoever strikes a man so that he dies shall be put to death”, and Leviticus 24:17 states that “he who kills a man shall be put to death.” The logical implication of the new teaching seems to be that Scripture therefore commanded nothing less than “an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person.” Yet the Church also teaches that Scripture is divinely inspired and cannot teach moral error. For example, the First Vatican Council declared that the Scriptures “contain revelation without error” and Pope Leo XIII taught that “it is absolutely wrong and forbidden… to admit that the sacred writer has erred.”

These assertions cannot possibly be reconciled. Either (a) capital punishment is not, after all, an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person; or (b) being an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person does not, after all, suffice to make an action inadmissible; or (c) scripture taught moral error. Something’s got to give. Notice, though, that we can’t take option (c) without entirely undermining Catholic moral theology, not to mention contradicting ecumenical councils and consistent papal teaching. And option (b) doesn’t really make sense. If a certain action against a person is at least in some cases admissible, then the person is not inviolable in that respect. Hence the only option possible is (a) – in which case the revision to the Catechism is in error.

Catholic critics of capital punishment sometimes respond: “What about slavery and divorce? The Church abandoned Old Testament teaching on those matters, so why not on capital punishment?” But there are two problems with this response. First, the Law of Moses never commands slavery or divorce. It merely tolerates them, and puts conditions on how they may be practiced. By contrast, it does positively command capital punishment in some circumstances. Hence to hold that capital punishment is intrinsically evil is to imply that scripture not only tolerated, but positively commanded, something that is intrinsically evil.

A second problem with this response is that if the Law of Moses really had positively commanded slavery and divorce, that would only exacerbate the problem, not mitigate it. To defend the revision of the Catechism against the charge that it attributes moral error to scripture, it will hardly do for the defender to attribute further moral errors to scripture!

(In addition, what most people think of when they hear the word “slavery” is chattel slavery – the kind we associate with the early history of the United States, which treats some human beings as the property of others in an unqualified sense. The Church never approved that evil practice in the first place, and that is not what scripture is talking about either. What was in question in the history of Catholic theology were practices like indentured servitude and penal servitude – servitude in payment of a debt or as punishment for a crime, respectively. Catholic capital punishment opponents who allege a parallel with slavery usually ignore these crucial distinctions.)

Then there is the teaching of previous popes. For example, in 1210 Pope Innocent III famously required the Waldensian heretics to affirm the legitimacy of capital punishment as a condition of their reconciliation with the Church. In other words, he taught that the legitimacy of capital punishment is a matter of Catholic orthodoxy. Pope Francis’s revision to the Catechism seems to imply that the heretics were right all along and that Pope Innocent led the faithful into grave moral error.

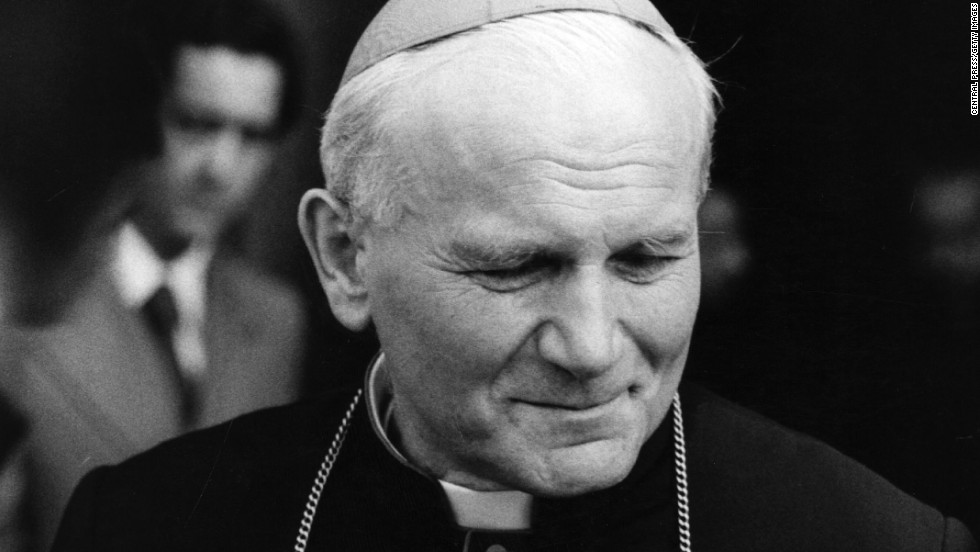

To take another example, the 1997 version of the Catechism promulgated by Pope St John Paul II acknowledges that “the traditional teaching of the Church does not exclude recourse to the death penalty” – though it also holds that “the cases in which the execution of the offender is an absolute necessity ‘are very rare, if not practically nonexistent.’” Pope Francis’s revision to the Catechism seems to imply, then, that John Paul II taught that the Church does not exclude what amounts to “an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person.” Indeed, it seems to imply that John Paul II taught that “an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person” can at least in some rare cases be an “absolute necessity”!

Then there is the Roman Catechism promulgated by Pope St Pius V and used by the Church for centuries, which teaches:

Another kind of lawful slaying belongs to the civil authorities, to whom is entrusted power of life and death, by the legal and judicious exercise of which they punish the guilty and protect the innocent. The just use of this power, far from involving the crime of murder, is an act of paramount obedience to this Commandment which prohibits murder. The end of the Commandment is the preservation and security of human life.

Pope Francis’s revision to the current Catechism therefore appears to imply that the Roman Catechism taught that “an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person” can be “an act of paramount obedience to [the] Commandment which prohibits murder”. In other words, Pope Francis’s teaching seems to imply that Pope St Pius V’s teaching was not only gravely in error, but perverse in the extreme.

Many further examples could easily be given of past magisterial teaching which, if the revision to the Catechism is correct, would have to be judged to have led the faithful into grave moral error. The legitimacy in principle of capital punishment is, after all, the consistent teaching of scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and the popes, for over two millennia. (Joseph Bessette and I set out the evidence at length in our book By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed.) Now, part of the problem is that, as I have argued elsewhere, the suggestion that the Church has been wrong for two millennia is flatly incompatible with what the Church claims about the reliability of her ordinary Magisterium. But another problem is that Pope Francis’s revision implies that popes and official catechisms are susceptible of error that is so grave, and so persistent, that it casts serious doubt on all papal and catechetical teaching – including his own. In short, the pope’s revision is essentially self-defeating.

- The new wording appears to reject traditional teaching about the purposes of punishment.

Pope Francis’s revision to the Catechism indicates that capital punishment was traditionally approved for two reasons: the protection of society, and proportional retribution. Let’s focus for now on the second of these. Traditional Catholic teaching holds that retributive justice is the fundamental purpose (even if not the only purpose) of the criminal justice system. Punishment, the Church has taught, fundamentally involves the infliction on an offender of a penalty proportionate to the gravity of his offence.

Commenting on this rationale, the revised text says:

Recourse to the death penalty on the part of legitimate authority, following a fair trial, was long considered an appropriate response to the gravity of certain crimes…

Today, however… a new understanding has emerged of the significance of penal sanctions imposed by the state.

Furthermore, the letter from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) that announced the change claims that in the teaching of John Paul II, “the death penalty is not presented as a proportionate penalty for the gravity of the crime.” The letter also asserts that the change in teaching about the death penalty “takes] into account the new understanding of penal sanctions applied by the modern State, which should be oriented above all to the rehabilitation and social reintegration of the criminal”, and that the older teaching reflected “a social context in which the penal sanctions were understood differently.”

In other words, the change to the Catechism seems to reject the traditional teaching on retributive justice, in favour of a “new understanding” that instead emphasises rehabilitation and reintegration.

The significance of such a change cannot be overstated. The traditional teaching has been consistently reaffirmed by the popes: St John Paul II himself did so both in Evangelium Vitae and in the Catechism he promulgated. The latter teaches:

Legitimate public authority has the right and duty to inflict punishment proportionate to the gravity of the offence. Punishment has the primary aim of redressing the disorder introduced by the offence. When it is willingly accepted by the guilty party, it assumes the value of expiation. [Emphasis added]

Fortunately, this passage survives in Pope Francis’s revision to the Catechism – which altered only the subsequent section, n. 2267. However, it is hard to see how to reconcile the new section 2267’s claim that the Church has a “new understanding… of the significance of penal sanctions” with section 2266’s explicit affirmation of the old understanding of the significance of penal sanctions.

Moreover, the CDF letter contains a strange set of assertions. It says that for John Paul II, the death penalty is “not presented as a proportionate penalty for the gravity of the crime”. But then Pope John Paul II did allow for capital punishment at least in rare circumstances. The CDF letter’s logical implication would seem to be that John Paul II taught that capital punishment could in principle be used even though it is not a proportionate penalty! But obviously, that cannot be what John Paul II thought. (As Joseph Bessette and I show in our book, the late pope did in fact implicitly teach that capital punishment is a proportionate penalty, and merely held that that was not sufficient to justify actually using it in most modern circumstances.)

Furthermore, the notion that the Church’s traditional teaching about the purposes of punishment might be replaced by a “new understanding” is one that Pope Pius XII explicitly rejected. For example, in his “Discourse to the Catholic Jurists of Italy”, published in 1955, Pius said:

[M]any, perhaps the majority, of civil jurists reject vindictive punishment… [H]owever… the Church in her theory and practice has maintained this double type of penalty (medicinal and vindictive), and… this is more in agreement with what the sources of revelation and traditional doctrine teach regarding the coercive power of legitimate human authority. It is not a sufficient reply to this assertion to say that the aforementioned sources contain only thoughts which correspond to the historic circumstances and to the culture of the time, and that a general and abiding validity cannot therefore be attributed to them.

So, Pius XII taught that the “vindictive” or retributive function of punishment is rooted in divine revelation and traditional doctrine, and explicitly rejected the suggestion that it merely reflects historical circumstances and lacks abiding relevance – whereas Pope Francis’s revision seems to imply the exact opposite.

The traditional teaching had a good reason for emphasising retribution and proportionate penalties. The reason is that if we don’t think in terms of giving an offender what he deserves, then we are no longer thinking in terms of justice at all. If all that matters is rehabilitating and reintegrating people, then we might, in theory, inflict extremely mild punishments or no punishment at all even for the most heinous crimes, if we think this is an efficient way to achieve these ends. And by the same token, we might inflict extreme penalties for minor crimes, or even on innocent people whose behaviour we want to alter. Nothing is ruled out, in principle, if we throw out considerations of giving offenders what they deserve. To be sure, the revision to the Catechism doesn’t explicitly go this far. But it muddies the waters considerably.

- The revision rests in part on empirical assertions that are dubious at best.

The revised text of the Catechism justifies a complete abolition of capital punishment in part on the grounds that “more effective systems of detention have been developed, which ensure the due protection of citizens.” The CDF letter adds that “the death penalty [is] unnecessary as protection for the life of innocent people.” However, this is in no way a doctrinal assertion. It is merely an empirical claim that is highly controversial at best – and indeed, in some contexts, manifestly false. Moreover, it concerns matters of social science about which the Church has no special expertise.

The first problem here is that though the “effective systems of detention” to which the revised text refers may exist in wealthy Western countries, there are still large regions of the undeveloped world where the most dangerous aggressors cannot be rendered harmless by incarceration. (Think of the unstable political orders in some African and Middle Eastern countries, or Mexican drug lord “El Chapo’s” escapes from prison.) The CDF statement and the revision to the Catechism are in this respect strangely Eurocentric in their outlook. Are the lives of potential innocent victims of violent crime in Third World countries of less value than those of wealthy Europeans and Americans?

A second problem is that even in First World countries, the most dangerous offenders sometimes remain a threat to the lives of others even when they are incarcerated for life. For example, they sometimes murder other prisoners and prison guards. Also, drug kingpins and others associated with organized crime sometimes order assassinations, from prison, of victims in the outside world.

A third problem is that the CDF letter and revision to the Catechism ignore the issue of the deterrence value of capital punishment. While some social scientists doubt its deterrence value, there are also many social scientists who, on the basis of peer-reviewed empirical studies, are convinced that the death penalty does significantly deter. The most that the abolitionist can reasonably say is that the matter is controversial. But if capital punishment really does deter some potential murderers, then innocent lives will be lost by abolishing the practice altogether. The CDF letter’s peremptory assertion that “the death penalty [is] unnecessary as protection for the life of innocent people” is therefore simply not supported by the empirical evidence. (See By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed for a detailed treatment of the evidence for deterrence.)

A fourth problem is that the revision to the Catechism ignores the fact that capital punishment gives prosecutors an invaluable negotiating tool. Violent offenders who would otherwise refuse to reveal accomplices or help solve other crimes are sometimes willing to talk if they can be assured that prosecutors will not seek their execution. When the death penalty is taken off the books altogether, this bargaining chip is gone – and once again, innocent people will pay the price.

In any event, churchmen have no special expertise on these matters. And of course, the essential point is not about these empirical issues, but about the authority of the Church’s perennial teaching – which raises a simple question. How can anyone justify a radical revision to over two millennia of scriptural and papal teaching on the basis of dubious amateur social science?

Edward Feser is the co-author of By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

I have just spent three hours trawling through this blog and I have to ask - what the fuck?

ReplyDeleteAs far as I know a blog is "a channel where you share your thoughts......a public journal, diary, or even book. You can share personal thoughts, quick updates, or even educate others on what you learned".

AS far as I can see all of this stuff is copied from newspapers and magazines - why do you bother re-posting stuff that is bollocks to begin with as if you had something to do with it? Haven't you got anything to say for yourself?

And does Clive James know that you have written posts pretending to be emails sent by him? That's a pretty shitty thing to do considering he's mortally ill. Well, if he doesn't know yet I'll see to it that he or his agent soon will - what sort of a shit pulls a stunt like that? I hope he will sue you and see you charged with false pretences. What a horrible person you must be.

Oh! Get stuffed Detterling.

ReplyDelete'And does Clive James know that you have written posts pretending to be emails sent by him?'

ReplyDeleteClive James has a sense of humour. Something you should develop fat man.