Tired from his long journey, Cohen knocked at the door of a boarding house. But the only thing it could offer was a camp bed in the living-room. Cohen, who always said he had 'a very messianic childhood’, accepted the accommodation and the landlady’s terms: that he get up every morning before the rest of the household, tidy up the room, get in the coal, light a fire and deliver three pages a day of the novel he told her he’d come to London to write.

Mrs Pullman ran a tight ship. Cohen, with his liking for neatness and order, happily accepted his duties. He had a wash and a shave then went out to buy a typewriter, a green Olivetti, on which to write his masterpiece. On the way he stopped in at Burberry on Regent Street and bought a blue raincoat. The dismal English weather failed to depress him. Everything was as it should be; he was a writer in a country where, unlike Canada, there were writers stretching back for ever: Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, Keats. Keats’s house, where he wrote Ode to a Nightingale, was 10 minutes’ walk from the boarding house. Cohen felt at home.

Despite its proximity to central London, Hampstead had the air of a village – a village that crawled with writers and thinkers. Among the permanent residents in Highgate Cemetery, a short walk away, were Karl Marx, Christina Rossetti, George Eliot and Radclyffe Hall. When London was shrouded in toxic smog, Hampstead, high on a hill, drew consumptive poets and sensitive artists with its cleaner air.

Cohen’s friend Mort Rosengarten had been the first of Cohen’s crowd to stay there, renting a room from Jake and Stella Pullman while at art school. Next was Nancy Bacal, who had gone to London to study classical theatre and stayed on to become a radio and television journalist. Bacal, like Cohen, had been given the 'starter bed’ and a hot-water bottle in the living-room, until Rosengarten moved out, and Mrs Pullman, judging her worthy, allowed her to take over his room. Which is where she was when Cohen showed up in December 1959.

Bacal, a writer and teacher of writing, cannot remember a time when she did not know Cohen. Like him, she was born and raised in the Westmount area of Montreal. They lived on the same street and went to the same Hebrew and high schools; her father was Cohen’s paediatrician.

'It was a very strong community, inbred in many ways, but in no way was he the usual person you’d find in the Westmount crowd. He was reading and writing poetry when people were more interested in who they were going to date for their Sunday school graduation. He pushed the borders from a very early age.’ She recalls the endless talks she and Cohen would have in their youth about their community, 'what was comfortable, where it left us wanting, where we felt people weren’t penetrating to the truth.’ Their conversation had taken a break when Bacal left for London, but when Cohen moved into the Pullmans’ house, it picked up where it had left off.

Stella Pullman, unlike most residents of Hampstead, was working class – 'salt of the earth, very pragmatic, down-to-earth English’ is Bacal’s description. 'She worked at an Irish dentist’s in the East End of London; took the Tube there every day. Everyone who lived in the house used to schlep down there once a year and have their fillings done. She was very supportive – Cohen still credits her with being responsible for him finishing the book because she gave him a deadline, which made it happen – but she was not what you’d call impressed by him, or by any of us. “Everyone has a book in them,” she’d say, “so get on with it. I don’t want you just hanging around.” She’d been through the war; she had no time for all that nonsense. Cohen was very comfortable there because there was no artifice about it. He and Stella got along very, very well. Stella liked him a lot – but secretly; she never wanted anyone to get, as she would say, “too full of themselves”.’

Cohen kept to his part of the agreement and wrote the required three pages a day of the novel he had begun to refer to as 'Beauty at Close Quarters’. In March 1960, three months after his arrival, he had completed a first draft.

Leonard Cohen at Mrs Pullman’s boarding house in Hampstead, 1960 (Courtesy Leonard Cohen)

Leonard Cohen at Mrs Pullman’s boarding house in Hampstead, 1960 (Courtesy Leonard Cohen)

Late at night, after closing time at the King William IV, their local pub, Bacal and Cohen would explore London together. 'To be in London in those times was a revelation. It was another culture, a kind of no-man’s-land between the Second World War and the Beatles. It was dark, there wasn’t much money and it was something we’d never experienced, the London working class – and don’t forget we’d started with Pete Seeger and all those working-man songs. We’d start out at one or two in the morning and wander way out to the East End and hang out with guys in caps with cockney accents. We’d visit the night people in rough little places, having tea. We both loved the street life, street food, street activity, street manners and rituals’ – all the things Cohen had been drawn to in Montreal. 'If you want to find Cohen,’ Bacal says, 'go to some little coffee bar or hole in the wall. Once he finds a place, that’s where he’ll go every night. He wasn’t interested in what was “happening”; he was interested in finding out what lay underneath it.’

Through her broadcast work Bacal became fam-iliar with London’s West Indian community, and started to frequent a cellar club on Wardour Street in Soho, the Flamingo. On Friday nights, after hours, it transformed into a club-within-a-club called the All-Nighter. It began at midnight, although anyone who was anyone knew it did not get going until 2am. 'It was, theoretically, a very dodgy place but it was actually magical,’ Bacal says. 'There was so much weed in the air it was like walking into a painting of smoke.’ The music was good – calypso and white R&B-jazz acts such as Zoot Money and Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames – and the crowd was fascinating. Quite unusually for the time, it was 50 per cent black – Afro-Caribbeans and a handful of African American GIs – the white half made up of mobsters, hookers and hipsters.

Cohen loved the place. He wrote to his sister Esther, 'It’s the first time I’ve really enjoyed dancing. I sometimes even forget I belong to an inferior race. The Twist is the greatest ritual since circumcision – and there you can choose between the genius of two cultures. Myself I prefer the Twist.’

With the first draft of his novel finished, Cohen turned his attention to his second volume of poems. He had gathered the poems for The Spice-Box of Earth the year before and had given it to the Canadian publisher McClelland & Stewart, hand-ing his manuscript to Jack McClelland in person. McClelland had taken over his father’s company in 1946 at the age of 24 and was, according to the writer Margaret Atwood, 'a pioneer in Canadian publishing’. So impressed was McClelland by Cohen that he accepted his book on the spot.

Poets are not especially known for their salesman skills, but Cohen worked his book like a pro. He instructed the publisher how it should be packaged and marketed. Instead of the usual slim hardback that poetry tended to come in – which was nice for pressing flowers in, but expensive to print and therefore buy – his should be a cheap, colourful paperback. 'I want an audience,’ he wrote to McClelland. 'I am not interested in the Academy.’ He wanted to make his work accessible to 'inner-directed adolescents, lovers in all degrees of anguish, disappointed Platonists, pornography-peepers, hair-handed monks and Popists, French-Canadian intellectuals, unpublished writers, curious musicians etc, all that holy following of my Art’. In all, a pretty astute, and remarkably enduring, inventory of his fan base.

Cohen was sent a list of revisions and edits and given a tentative publication date of March 1960, but the date passed. In the same month, he was walking to the Tube station from the dental surgery where Mrs Pullman worked, where he had just had a wisdom tooth pulled. It was raining – Cohen would say 'it rained almost every day in London’, which sounds about right – but that day it rained even more heavily than usual, that cold, sideways, winter rain in which England specialises. He took shelter in a nearby building, which turned out to be a branch of the Bank of Greece. Cohen could not fail to notice that the teller wore a pair of sunglasses and had a tan. The man told Cohen that he was Greek and had recently been home; the weather, he said, was lovely there at this time of year.

There was nothing to keep Cohen in London. He had no project to complete or promote, which left him not only free, but also vulnerable to the depression that the short, dark days of a London winter are so good at inducing. On Hampstead High Street he stopped in at a travel agent’s and bought tickets to Israel and Greece.

He had no problem with leaving one place and moving to another – he travelled light and wasted little time on sentimentality. But wherever he lived, he liked to surround himself with fellow thinkers: people who could hold a conversation, hold a drink and knew how to hold their silence when he needed to be left alone to write. An acquaintance in London, Jacob Rothschild, whom he had met at a party, had talked about a small Greek island named Hydra. Rothschild’s mother, Barbara Hutchinson, was about to be remarried to a celebrated Greek painter, Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas, who had a mansion there. Rothschild suggested that Cohen go and visit them. The island’s small population included artists and writers from around the globe. Henry Miller had lived there at the start of the Second World War and written in The Colossus of Maroussi about its 'wild and naked perfection’.

After leaving London, Cohen stopped first in Jerusalem. It was his first time in Israel. By day he toured the ancient sites and at night he sat in the Café Kasit, the haunt of 'everybody that thought they were a writer’. After a few days, Cohen took the plane to Athens. He stayed in the city one day, during which he saw the Acropolis. In the evening he took a cab to Piraeus and checked into a hotel down by the docks. Early the next morning, Cohen boarded a ferry to Hydra.

In 1960, before there were hydrofoils, it was a five-hour journey. But there was a bar on board. Cohen took his drink up on deck and sat in the sun, staring out at the rumpled blue sheet of sea, the smooth blue blanket of sky, as the ferry chugged slowly past the islands scattered like a broken necklace across the Aegean.

As soon as he set eyes on Hydra, before the ferry even entered the port, Cohen liked it. Everything about it looked right: the natural, horseshoe-shaped harbour, the whitewashed buildings on the steep hills surrounding it. When he took off his sunglasses and squinted into the sun, the island looked like a Greek amphitheatre, its houses like white-clad elders sitting upright in the tiers.

The doors of the houses all faced down to the port, which was the stage, on which a very ordinary drama unfolded: boats bobbing lazily on the water, cats sleeping on the rocks, young men unloading the day’s catch of fish and sponges, old men tanned like leather sitting outside the bars arguing and talking. When Cohen walked through the town, he noticed that there were no cars. Instead there were donkeys, with baskets hung on either side, lumbering up and down the steep cobblestone streets between the port and the Monastery of the Prophet Elijah. It might have been an illustration from a children’s Bible.

The place appeared to have been organised according to some ancient ideal of harmony, symmetry and simplicity. The island had only one real town, named simply Hydra Town. Its inhabitants had come to a tacit decision that two basic colours would suffice – blue (the sea and the sky) and white (the houses, the sails and the seagulls circling over the fishing boats). 'I really did feel I’d come home,’ Cohen said later. 'I felt the village life was familiar, although I’d had no experience with village life.’ What might have also given Hydra its feeling of familiarity was that it was the nearest thing Cohen had experienced to the Utopia he and Rosengarten used to discuss as boys in urban Montreal. It was sunny and warm and it was populated by writers, artists and thinkers from around the world.

The village chiefs of the expat community were George Johnston and Charmian Clift. Johnston, 48 years old, was a handsome Australian journalist who had been a correspondent during the Second World War. Charmian, 37, also a journalist, was his attractive second wife. Both had written books and wanted to devote themselves to writing full-time. The fact that they had children necessitated finding a place to live where life was cheap but congenial. They discovered Hydra in 1954. The couple were great self-mythologisers and natural leaders. They held court at Katsikas’s, a grocery store on the waterfront whose back room, with perfect Hydran simplicity, doubled as a small cafe and bar. The handful of tables outside overlooking the water made the ideal spot for the expats to gather and wait for the ferry, which arrived at noon, bringing the mail – all of them seemed to be waiting for a cheque – and a new batch of people, to watch, to talk to, or to take to bed. On a small island with few telephones and little electricity, therefore no television, the ferry provided their news, their entertainment and their contact with the outside world. Cohen met George and Charmian almost as soon as he arrived.

He was not the first young man they had seen walking from the port carrying a suitcase and a guitar, but they took to him immediately, and he to them. The Johnstons were colourful, charismatic and anti-bourgeois. They had also been doing for years what Cohen had wanted to do, which was live as a writer without the necessity of taking regular work. They had very little money but on Hydra they could get by on it, even with three children to provide for, and the life they were living was by no means impoverished. They lunched on sardines fresh off the boat, washed down with retsina – which old man Katsikas let them put on a tab – and seemed to glow in the warmth and sun. Cohen accepted their invitation to stay the night. The next day they helped him rent one of the many empty houses on the hill, and donated a bed, chair and table and some pots and pans.

Cohen was happy with very little. He thrived in the Mediterranean climate. Every morning he would rise with the sun, just as the local workmen did, and start his work. After a few hours’ writing he would walk down the narrow, winding streets, a towel flung over one shoulder, to swim in the sea. While the sun dried his hair, he walked to the market to buy fresh fruit and vegetables, and climbed back up the hill. It was cool inside the old house. He would sit writing at the Johnstons’ wooden table until it was too dark to see by the kerosene lamps and candles. At night he walked back again to the port, where there was always someone to talk to.

The ritual, routine and sparsity of this life satisfied him immensely. It felt monastic somehow, except that the Hydra arts colony had beaten the hippies to free love by half a decade. Cohen was also a monk who observed the Sabbath. On Friday nights he would light candles and on Saturday, instead of working, he would put on his white suit and go down to the port to have coffee.

Leonard Cohen and Marianne Jensen (Courtesy Leonard Cohen)

One afternoon, towards the end of the long, hot summer

Leonard Cohen and Marianne Jensen (Courtesy Leonard Cohen)

One afternoon, towards the end of the long, hot summer, a letter arrived by ferry for Cohen. It told him that his grandmother had died, leaving him $1,500. He already knew what he would do with it. On September 27 1960, days after his 26th birthday, Cohen bought a house on Hydra. It was plain and white, three storeys high, 200 years old, one of a cluster of buildings on the saddle between Hydra Town and the next little village, Kamini. It was a quiet spot, if not entirely private – if he leant out of the window, he could almost touch the house across the alley, and he shared his garden wall with the next-door neighbour.

The house had no electricity, nor even plumbing – a cistern filled in spring when the rains came, and when that ran out he had to wait for the old man who came past his house every few days with a donkey weighted on both sides with containers of water. But the house had thick white walls that kept the heat out in summer, a fireplace for the winter and a large terrace where Cohen smoked, birds sang and cats skulked. A priest blessed the house, holding a burning candle above the front door and making a black cross in soot. An elderly neighbour, Kiria Sophia, came early every morning to wash the dishes, sweep the floors, do the laundry, look after him. Cohen’s new home gave him the pure pleasure of a child.

'One of the things a lot of people haven’t caught,’ Steve Sanfield, a long-time close friend of Cohen, says, 'is really how important those Greece years and the Greek sensibility were to Cohen and his development and the things he carries with him. Cohen likes Greek music and Greek food, he speaks Greek pretty well for a foreigner, and there’s no rushing with Cohen, it’s, “Well, let’s have a cup of coffee and we’ll talk about it.” He and I both carry komboloi – Greek worry beads; only Greek men do that. The beads have nothing to do with religion at all – in fact one of the Ancient Greek meanings of the word is “wisdom beads”, indicating that men once used them to meditate and contemplate.’

Sanfield’s friendship with Cohen began 50 years ago, when Sanfield boarded a ferry in Athens and, on a whim, alighted at Hydra, 'a young poet seeking adventure’. His memories of Hydra are of sun, camaraderie, the voluptuous simplicity of life, and the energy that emanated from its small community of artists and seekers – about 50 in number, although people would come and go. The mainstays, the Johnstons, 'were vital in all of our lives. They fought a lot, they sought revenge on each other a lot with their sexuality, and things got very complicated, but they were really the centre of foreign life in the port.’ Among the other residents were Anthony Kingsmill, a British painter, raconteur and bon vivant to whom Cohen became close; Gordon Merrick, a former Broadway actor and reporter whose first novel, The Strumpet Wind, about a gay American spy, was published in 1947; and Dr Sheldon Cholst, an American poet, artist, radical and psychiatrist who set his flag somewhere between Timothy Leary and RD Laing.

'A lot of people came through in those early years,’ Sanfield says, 'like Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso,’ the latter of whom was living on the neighbouring island, coaching a softball team. Cohen met Ginsberg on a trip to Athens. Cohen was drinking coffee in St Agnes Square when he spotted the poet at another table. 'I went up to him asked him if he was indeed Allen Ginsberg, and he came over and sat down with me and then he stayed in my house on Hydra, and we became friends. He introduced me to Corso,’ Cohen said, 'and my association with the Beats became a little more intimate.’ Hydra in the early 1960s was according to Sanfield, 'a golden age of artists. We weren’t beatniks, and hippies hadn’t been invented yet, and we thought of ourselves as kind of international bohemians or travellers, because people came together from all over the world with an artistic intent. There was an atmosphere there that was very exciting.’

Another expat islander who played a part in Cohen’s life was Axel Jensen. A lean, intense Norwegian writer in his late 20s, he had published three novels, one of which became a film. The house where Jensen lived with his wife, Marianne, and their young child, also named Axel, was at the top of Cohen’s hill. Sanfield stayed in the Jensens’ house when he first arrived on Hydra; the family had rented it out while they were away. Its living-room was carved out of the hillside.

When Marianne came back to the island, her husband was not with her. 'She was the most beautiful woman I’d ever known,’ Sanfield says. 'I was stunned by her beauty and so was everyone else.’ Cohen included. 'She just glowed, this Scandinavian goddess with this little blond-haired boy, and Cohen was this dark Jewish guy. The contrast was striking.’

Cohen had fallen in love with Hydra the moment he saw it. It was a place, he said, where 'everything you saw was beautiful, every corner, every lamp, everything you touched, everything’. The same thing happened when he first saw Marianne. 'Marianne,’ he wrote to his lifelong friend the poet Irving Layton, 'is perfect.’

'It must be very hard to be famous. Everybody wants a bit of you,’ Marianne Ihlen says now with a sigh. There were muses before Marianne in Cohen’s poetry and song and there have been muses since; but if there were a contest, the winner, certainly the people’s choice, would be Marianne. Only two of Cohen’s non-musician lovers have had their photographs on his album sleeves, and Marianne was the first. On the back of Songs from a Room, Cohen’s second album, there she sat, in a plain white room, at his simple wooden writing table, her fingers brushing his typewriter, her head turned to smile shyly at the camera, and wearing nothing but a small white towel.

Leonard Cohen and Marianne Jensen in Hydra’s harbour with George Johnston

Leonard Cohen and Marianne Jensen in Hydra’s harbour with George Johnston

and Johnston’s second son, Jason, in 1960 (Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

Ihlen, now in her mid-70s, has a kind, round face deeply etched with lines. Like Cohen, she does not enjoy talking about herself but is too considerate to say no. She is as modest and apologetic about her English, which is very good, as she once was about her looks. Despite having been a model, she could never understand why Cohen would say she was the most beautiful woman he’d ever met. At the age of 22, 'blonde, young, naive and in love’, she had to the chagrin of her traditional Oslo family run off with Jensen, travelled around Europe, bought an old Volkswagen in Germany and driven it to Athens.

An old woman invited them to stay and let them leave their car in her overgrown garden while they took a trip around the islands. On the ferry they met a fat, handsome Greek named Papas, who lived in California, where he had a sweets and biscuits company that bore his name. They told him they were looking for an island. 'He told us to get off at the first stop; it was Hydra.’

It was mid-December, cold and raining hard. There was one cafe open at the port and they ran for it. It was neon-lit inside and warmed by a stove in the middle of the room. As they sat shivering beside it, a Greek man who spoke a little English told them of another foreign couple living on the island – George Johnston and Charmian Clift – and offered to take them to their house. And so it all began. Axel and Marianne rented a small house – no electricity, outside lavatory – and stayed, Axel writing, Marianne taking care of him. When the season changed, Hydra came alive with visitors, and the two poor, young, beautiful Norwegians found themselves invited to cocktail parties in the mansions of the rich. 'One of the first people that we met was Aristotle Onassis,’ Ihlen recalls. During their time on Hydra, people of every kind drifted by. And there was Cohen.

Much had happened in Ihlen’s life in the three years between her arrival on Hydra and Cohen’s. Ihlen and Jensen had broken up, made up, then married. They had bought an old white house on top of the hill at the end of the Road to the Wells. When the rains came, the street became a river that rushed like rapids over the cobblestones down to the sea. Her life with Jensen was turbulent. The locals talked about Jensen’s heavy drinking, how, when he was drunk he would climb up the statue in the middle of the port and dive from the top, head first. Marianne, they said, was a hippie and an idealist. She was also pregnant. She went back to Oslo to give birth. When she returned to Hydra with their son, she found Jensen packing, getting ready to leave with an American woman he told his wife he had fallen in love with. In the midst of all this, Cohen showed up.

She was shopping at Katsikas’s when a man in the doorway said, 'Will you come and join us? We’re sitting outside.’ She could not see who it was – he had the sun behind him – but it was a voice, she says, that 'somehow leaves no doubt what he means. It was direct and calm, honest and serious, but at the same time a fantastic sense of humour.’ She came out to find the man sitting at a table with the Johnstons. 'He looked like a gentleman, old-fashioned – but we were both old-fashioned,’ Ihlen says. When she looked at his eyes, she knew she 'had met someone very special. My grandmother said to me, “You are going to meet a man who speaks with a tongue of gold, Marianne.”’

They did not become lovers immediately. 'Though I loved him from the moment we met, it was a beautiful, slow movie.’ They started meeting in the daytime, Cohen, Marianne and little Axel, to go to the beach. Then they would walk back to Cohen’s house, which was closer than her own, for lunch and a nap. While Marianne and the baby slept, Cohen would sit watching them, their bodies sunburnt, their hair white as bone. Sometimes he would read her his poems. In October Marianne told Cohen she was going back to Oslo; her divorce proceedings were under way. Cohen told her he would go with her. The three took the ferry to Athens and picked up her car, and Cohen drove them from Athens to Oslo, more than 2,000 miles.

From Oslo Cohen flew to Montreal. If he were to stay on his Greek island, cheap as it was, he needed more money. From his rented apartment on Mountain Street he wrote to Marianne telling her of all his schemes. He was 'working very hard’, he said, on some television scripts with Irving Layton. 'Irving and I think that with three months of intense work we can make enough to last us at least a year. That gives us nine months for pure poetry.’ As for his second book of poetry, The Spice-Box of Earth, that would be published in the spring. There would be a book tour, too, and he wanted Marianne to come with him. The telegram he sent was short but effective: 'Have a flat. All I need is my woman and her child.’ Marianne packed two suitcases and flew with little Axel to Montreal

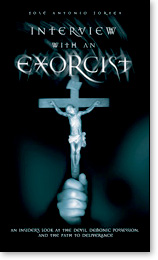

We live in a skeptical age, one which finds the very idea of personified evil spirits to be a superstitious remnant of the Middle Ages. Those people — and religious traditions — who believe in the existence of the devil and demons are often ridiculed as being out of touch with modern times. The contemporary Western mentality is that evil is merely the result of an inadequate social environment or due to purely psychological factors, causes which can be remedied with a social program or medication. In this view, the only "exorcisms" necessary are those which rid our society of poor social conditions, ignorance, or psychopathology. Many Christians — among them not a few Catholics — have succumbed to this mentality as well. They are formed more by the culture in which we live than by the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the teaching of the Church.

We live in a skeptical age, one which finds the very idea of personified evil spirits to be a superstitious remnant of the Middle Ages. Those people — and religious traditions — who believe in the existence of the devil and demons are often ridiculed as being out of touch with modern times. The contemporary Western mentality is that evil is merely the result of an inadequate social environment or due to purely psychological factors, causes which can be remedied with a social program or medication. In this view, the only "exorcisms" necessary are those which rid our society of poor social conditions, ignorance, or psychopathology. Many Christians — among them not a few Catholics — have succumbed to this mentality as well. They are formed more by the culture in which we live than by the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the teaching of the Church.

The focus of the Jimmy Savile affair shifted this week to questioning why the BBC, the press and the Establishment failed to investigate the rumours of his crimes. Here, a survivor of clerical abuse in Ireland highlights how a culture of institutional denial allowed these scandals to go unchecked

The focus of the Jimmy Savile affair shifted this week to questioning why the BBC, the press and the Establishment failed to investigate the rumours of his crimes. Here, a survivor of clerical abuse in Ireland highlights how a culture of institutional denial allowed these scandals to go unchecked